A recent study by investment advisory firm Cliffwater LLC highlights the costly pitfalls of the overly optimistic rate of return assumptions and associated investment risks borne by public pension plans. Per the agency’s findings, from 2000 to 2018 state pensions collectively returned an asset-weighted annual return of just 5.87 percent, badly trailing their own 7.75 percent asset-weighted return assumption over that same timeframe.

Those who closely follow public pension policy debates know by now that state and local governments rely heavily on projected investment returns to fund the promised defined benefit (DB) pensions. However, as the Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation has previously highlighted, more often than not these projections have proven to be overly optimistic. Worse, public sector retirement funds have increasingly taken a “high–risk/high–reward” approach by allocating their assets in more volatile investments in hopes for higher returns. The Cliffwater report provides further support of this understanding.

Investment Returns

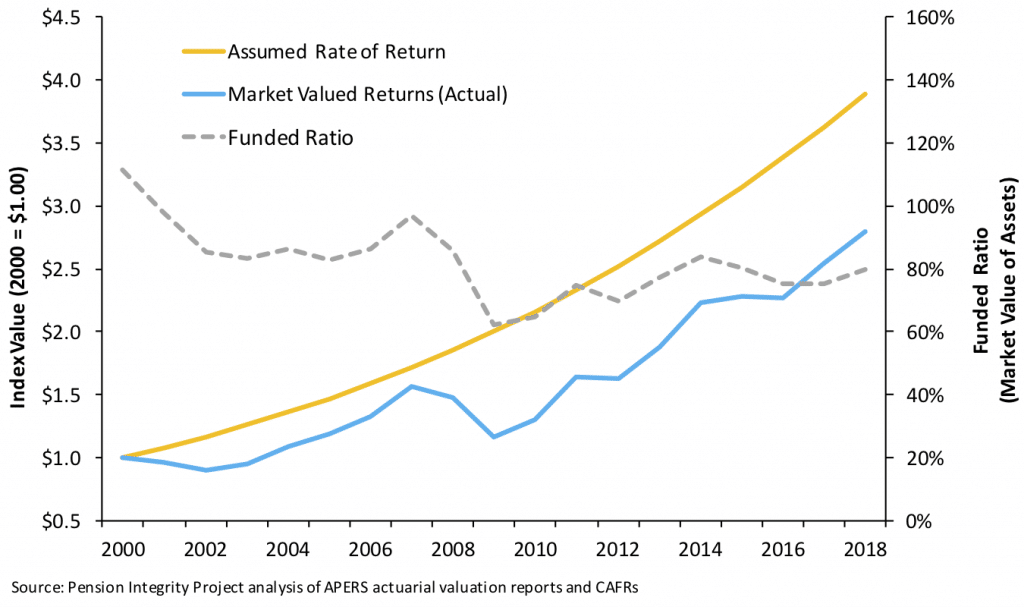

Cliffwater is quick to point out that the historical performance shortfall—with asset-weighted annual returns over the past 18 years collectively falling almost two percentage points below the public pension funds’ assumptions—contributed greatly to a decline in pension funding ratios from close to 100 percent (i.e. holding all the funds needed to provide promised retirement benefits) in 2000 to just 73 percent in 2018.

The Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System (APERS) is one of many examples (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. APERS Actual vs. Assumed Investment Growth

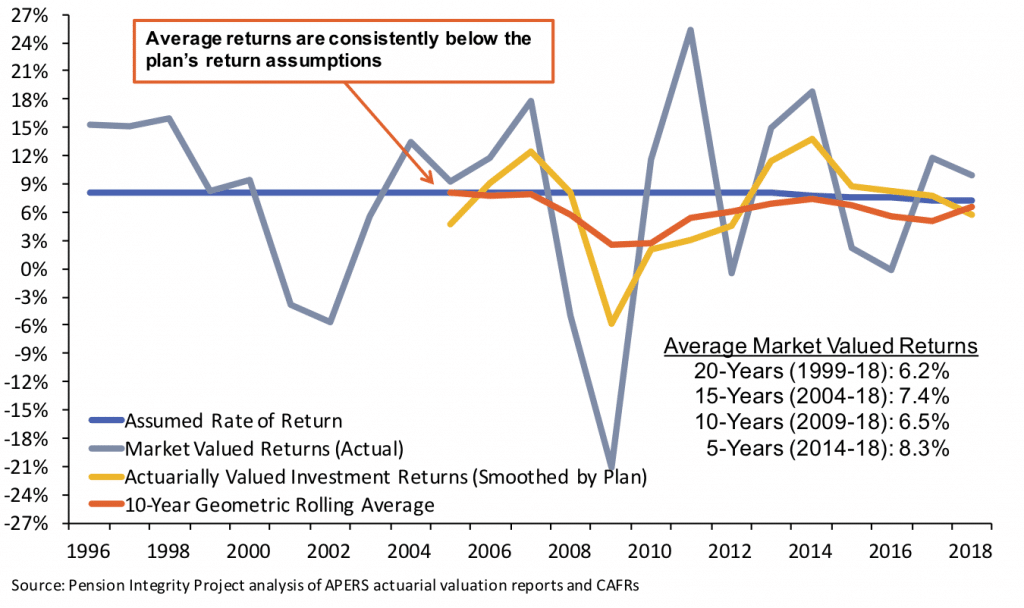

Another way to make the same point is to look at compounded historical returns for any given 10-year period (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. APERS Investment Return History

APERS, earned just 6.2 percent in the past 20 years on average (on a geometric/compound return basis), which added as much as $1.74 billion to its existing unfunded pension liabilities over that period.

Given this, the importance of fine-tuning return assumptions is often brought up in public pension policy debates. The Cliffwater analysis, for example, highlights how actual compound returns often fall behind the simply observed average rates. That is because the compound returns depend on a public pension funds’ year-over-year changes in the amount they invest. It means that positive returns, above the return assumption, combined with large amounts of assets invested, can produce disproportionately large material gains.

By the same token, however, an extended period of bad returns, and therefore severely depleted asset base, may not be made up even with double-digit returns later down the road.

“The first thing you have to do is make up what you lost,” said Sandy Matheson, executive director of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System. “And it takes years. And then you have to make up what you didn’t earn on what you didn’t have. It’s a pretty steep climb.”

Investment Risks

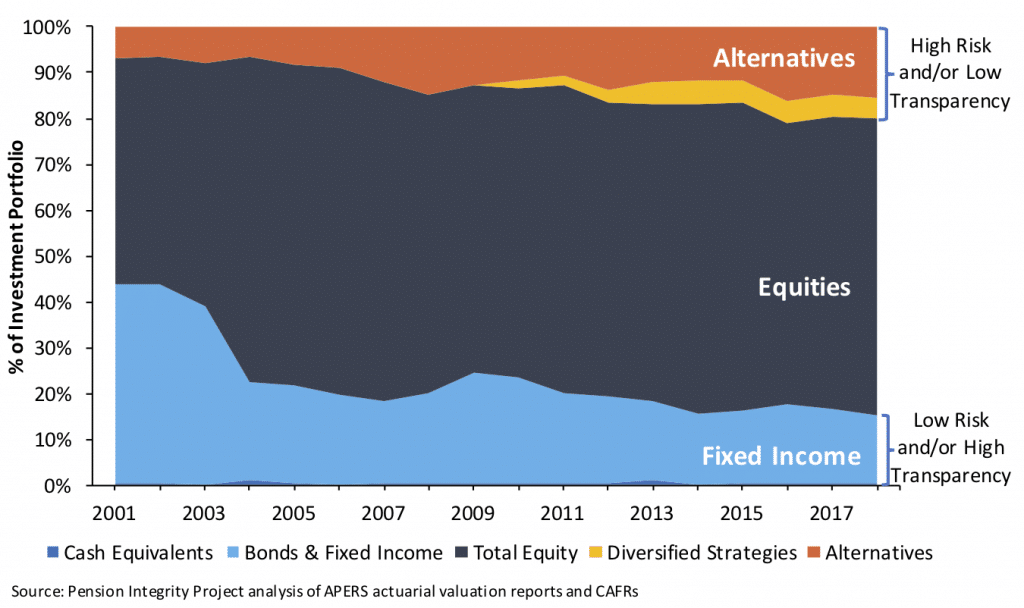

The report also finds that most of the increase in investment risk (or year-over-year volatility of investment returns) is driven by the market performance in equities. Asset allocations in equities among public DB pension plans has been steadily growing for the past decade, nearly reaching the exorbitant pre-2007-08 financial crisis levels. As such, public pension systems across the states appear to be embracing—instead of curbing—this increase in volatility.

The 79.6 percent funded APERS is a part of the growing trend to dedicate more of its assets to risky, and therefore more volatile, investments like equities and alternatives, including real estate and private equities (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. APERS Asset Allocations

According to the Cliffwater, global stock movements explain almost 92 percent of state pension asset volatility (designated by the correlation between the individual state pension fiscal year returns and the global equity market index (MSCI ACWI Index).

In other words, these statistics suggest that the future health of state and local pension systems is intertwined, to some degree, with the performance of the global stock markets. Other factors effecting financial health include whether the government makes full annual contributions, the amortization methods used, and other actuarial experiences.

Generally, the average state pension risk is measured by the standard deviation of fiscal year returns. Cliffwater finds that the average risk equals a standard deviation of 10.59 percent over the 18-year study period, versus 17.26 percent for the MSCI ACWI Index. As an example, APERS’s year-over-year fluctuations of investment returns increased from around 8 percent before 2009 to around 14 percent today (see Figure 4 below).

Graph 4. APERS 10-Year Rolling Average Returns Vs. Volatility

What’s the future?

Horizon Actuarial Services, LLC—which last year surveyed almost three dozen investment firms—expects the 10-year return forecast for diversified institutional pension portfolios to average out to 5.95 percent. This is just slightly north of the 18-year 5.87 percent asset-weighted actual return of state pension plans estimated by Cliffwater.

Not only that, investment consultants, such as Vanguard, predict around 30 percent chance of the U.S. economy plunging into a financial crisis this year, with risks ramping up going forward. The last recession resulted in state and local retirement systems losing as much as 28 percent of their assets, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. However, it is worth noting that even a mild market downturn, especially stretched over several years, will still hurt public pension funds’ finances.

The Cliffwater analysis serves as an insightful reminder of the pitfalls associated with using optimistic investment return assumptions, along with risky asset allocations. It highlights the need for explicit de-risking strategies and stress testing. Responsible management of public pension funds must address these factors, as they directly affect the retirement security of teachers, police officers, park managers, and other public workers.