On July 15, the parents of about 60 million American children began receiving monthly direct deposits or checks of up to $300 under the American Rescue Plan passed by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden. Carrying a $15 billion price tag, the benefits will increase the size of the child tax credit from $2,000 to $3,600 for children under six or to $3,000 for children between six and 17. The new law also makes the credit payable monthly instead of as an April refund and will widen its availability to families that do not file income taxes, which tends to be those who are most often below the poverty line.

The expanded child tax credit will impact more than just low-income families, with the credit gradually phasing out for families with incomes between $112,500 and $400,000. The Biden administration intends to extend the monthly child tax credit payments from one year to five and this provision is a part of the American Families Plan, which is now being debated by Congress.

The American Rescue Plan and American Families Act touch on so many friction points in ongoing debates over economic policy—poverty, welfare, basic income, COVID-19, federal stimulus funds, government debt and deficits—that a full accounting of the proposal’s pros and cons is beyond the scope of one article. Instead, this article will focus on the child tax credit’s use as an anti-poverty measure.

President Biden is correct that the tax credit will be of significant help to low-income families, though using deficit spending means especially high costs for federal taxpayers as a whole. However, to further improve lives and strengthen families, we must significantly change the way we understand, measure, and respond to poverty.

Slashing Poverty Rates, Lifting Incomes

Proponents of the new child tax credit claim the program will slash poverty rates and lift millions of children out of poverty. President Biden said the payments could be “life-changing for so many families,” while Vice President Kamala Harris called July 15 “the day the American family got so much stronger.” Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) called the plan “the single biggest blow to child poverty in American history.”

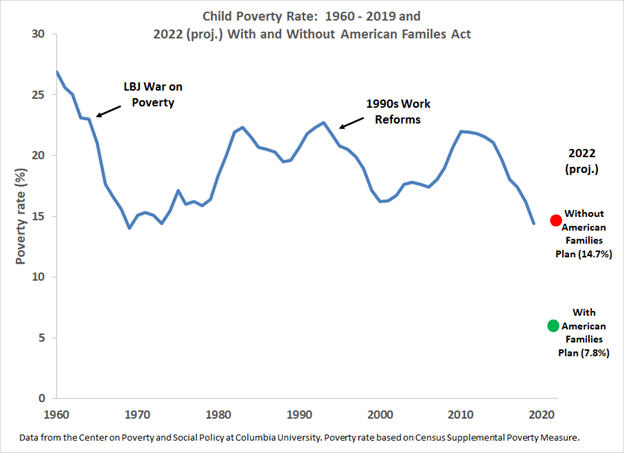

The Center on Poverty and Social Policy (CPSP) at Columbia University projects that if the longer-term American Families Act is passed, the result in would be a 47.4 percent reduction in the U.S. child poverty rate in 2022.

This calculation uses a poverty rate defined by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which attempts to account for not just income, but tax credits and non-cash welfare benefits like Medicaid, along with geographic variations in the cost of living. The Census Bureau began publishing the SPM in 2011, but in previous work, the CPSP estimated a historical series back to the early 1960s. The chart below shows the SPM-derived child poverty rate by year:

The graph clearly illustrates that overall economic conditions greatly impact the child poverty rate, with increases coinciding with the recessions of the early 1980s and 1990s as well as the great recession. The drop in poverty the American Families Plan is projected to cause follows these historical trends.

In the five years following 1964, when President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty” began, the child poverty rate fell from 23 percent to 14 percent. Most of Johnson’s new programs were new entitlements for lower-income Americans, such as Medicaid and education programs like Head Start and Pell grants. These benefits, along with general economic expansion, put many formerly poor children over the poverty line.

Another large decrease in the child poverty rate took place in the 1990s when the earned income tax credit tripled and work requirements for benefits changed. This meant the unconditional cash benefits of the New Deal-era, like Aid for Families with Dependent Children, turned into the welfare-to-work Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The drop in poverty is likely due in part to some people entering the workforce, as well as another period of widespread economic expansion.

There is some dissonance between these historical and projected slashings of the poverty rate versus a simple “eye test” or facts on the ground when we observe poverty in the United States today. Despite the fact that poverty, as measured by the SPM, is nearing an all-time low, there are great concerns and debates about economic inequality. There are also understandable tensions in many poor communities over overcriminalization, failed policing practices and other undeniable racial and economic disparities have reached a boiling point in recent years. Similarly, the closure of many factories coupled with an increase in opioid-related deaths has also put a spotlight on poverty in small towns and rural areas.

As we repeatedly try to “lift” millions out of poverty, why does the issue of poverty itself become even more politically contentious, and for some families and communities even more entrenched?

What’s Missing From the Poverty Discussion

We have a “birds’ eye view problem” in the way we observe, understand, and debate issues related to poverty.

We speak of millions being lifted from poverty because government benefits happen to raise millions of incomes above a line that, even with the adjustments made in the Supplemental Poverty Measure, remains to a great extent arbitrary. We rely on these top-line aggregate statistics for economic policy and they can be informative and often necessary in a country with a population of more than 300 million. However, the focus on these poverty statistics leads to viewing groups of millions of individuals as two-dimensional and homogenous.

An extra few thousand dollars per year going to low-income parents may be a great help to them. Unfortunately, when it is then reported that data shows millions of individuals have been pushed over the poverty line, many seem to believe that this means millions of families’ problems have been solved.

Likewise, the idea that unconditional welfare benefits discourage self-sufficiency on a cultural level suffers from the same birds’ eye view problem. In research I am currently conducting I find that the work-based welfare reforms of the 1990s were of limited benefit and that shifting people from unemployed poor to working poor had done little by itself to reduce poverty.

What’s missing from the national discussion on poverty becomes clearer when we think about economic and general prosperity in our own lives. In policy discussions, especially those relating to the poor, we often treat jobs as ends unto themselves. But many readers, considering their own careers, should have no trouble understanding work and jobs as means to broader—if hard to quantify—ends, such as a meaningful and productive life that benefits not just ourselves but our families and numerous others in our communities and networks.

Social capital can at times feel like a buzzword. But for many of us, its value becomes clear when we consider the role our many overlapping networks of relationships—family, friends, professional connections, neighborhoods and communities, groups of common interest—have played in our career path and more traditional measures of prosperity. To view this primarily as nepotism or cronyism misses the point. I would wager heavily that most readers found the opportunity that became their current job due to people they know, perhaps an explicit tip from a friend or basic knowledge of an industry and its firms gradually developed and shared among colleagues at one’s previous job.

Unfortunately, since the mid-20th century developments in both urban and rural poor communities have destroyed wealth, job opportunities, human capital, and the bonds and networks that fuel social capital. Urban, mostly black, communities have experienced a litany of terribly misguided if not malicious government policies including redlining, slum clearance, the building of housing projects, and hugely disparate incarceration rates.

Small towns and rural areas have similarly seen the loss of factories and the jobs that not only paid them but were often the institutions their communities were built around. These rural trends are the result of global forces that most economists agree are long-term positive but involve struggles and transitions for some that in this case have unfolded over decades.

People Lifting People

This more complex understanding of poverty may actually sound a note of highly cautious optimism for the reformed child tax credit as an unconditional welfare benefit. First, this perspective may reduce concerns that the new credit takes us back to the bad old days when handouts bred welfare dependency among the poor. Given all the other terrible, concurrent government policy, along with manufacturing towns being swept up in global trends, our approach to welfare policy appears to fall dramatically on the list of reasons we still haven’t won President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty.

Second, helping people meet basic needs without behavioral requirements or endless bureaucracy may free up time and resources for people to cultivate the kinds of personal, business, social, and community relationships that only they can build and are essential to robust prosperity. That’s why some economists would like to see many more of the nearly hundred welfare programs, most of which are weighed down by requirements and bureaucracy, replaced with similar cash aid. But such reforms would likely provoke significant resistance from both the left and right and are more realistic as a long-term goal.

Luckily, there are other possibly more immediate and feasible ways to enable and empower poor Americans to build the robust prosperity only they can create from the bottom up. Writing in Reason, Angela Rachidi and Naomi Schaeffer-Riley provide a lengthy list of unnecessary regulations that disproportionately impact the poor and need reform—health insurance flexibility, occupational licensing reform, childcare and zoning regulations, to name just a few.

We can lift incomes and slash poverty rates, and we can help people whose communities have been robbed of capital of all kinds. But we need to stop, as much as possible, restraining the hands of those trying to lift themselves out of poverty in a meaningful and lasting way.