In Dec. 2020, Pennsylvania’s Public School Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS) reported it had earned a 6.38 percent return for the previous nine years. This return narrowly cleared a 6.36 percent benchmark that, when missed, triggers higher contributions for newer employees in the pension plan under the shared-risk provisions enacted by the state in 2010 and 2017. This March, however, the Public School Employees’ Retirement System’s (PSERS) board revealed that the reported investment return rate was incorrect and the revised return of 6.34 percent would result in an increase in employee contribution rates. PSERS said the rate hike would range from 0.5 to 0.75 percent of staff salaries.

Shortly after this news was disclosed, the FBI unveiled an investigation into the public pension fund. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported:

The federal investigation of Pennsylvania’s $64 billion pension fund for teachers has come into sharper focus with reports that officials are examining both the plan’s inflated estimates of its returns and its spending spree on Harrisburg real estate.

The probe by federal prosecutors and the FBI is exploring how top executives of the fund, known as PSERS, responded when word spread internally that its financial performance might fall short of its official goal, The Inquirer has learned.

Last month, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission widened the investigation, according to the Pittsburgh Tribune:

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has widened the federal scrutiny of Pennsylvania’s mammoth public school pension plan, demanding records that could show whether the fund’s staff improperly traded gifts with any of hundreds of Wall Street consultants and investment managers.

The SEC’s new 30-page subpoena comes six months after the U.S. Attorney’s office in Philadelphia and the FBI opened a criminal investigation into possible bribery linked to exaggerated investment returns and Harrisburg land deals at the agency.

While the turmoil surrounding PSERS is newsworthy, many of the fundamental challenges facing the pension system are not unlike those facing other public pension plans’ asset management: high fees, underperformance, and a lack of investment transparency as plan managers attempt to chase increasingly unrealistic investment return targets.

The Outlook for PSERS

PSERS was 100 percent funded in 2002, but since then the pension plan has accumulated more than $44 billion in unfunded liabilities. 2020 reports show the plan is below 60 percent funded, meaning it doesn’t have the money to pay for retirement benefits already promised to workers. In August, Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project and other groups were invited to present to a multi-day set of pension-related hearings convened by the House State Government Committee related to the financial solvency of PSERS and the separate state pension system covering state employees.

Public pension plan funding, generally, has suffered in the last two decades due to several severe market downturns and aggressive monetary policy that stripped fixed-income investments, a previous workhorse of pensions, of their yield. Instead of adequately adjusting plan assumptions about investment returns and contribution rates, many public pension plans in the U.S. sought to maintain high investment returns through riskier investments, like alternative assets. In 2020, PSERS allocated nearly two-thirds of its assets to alternative investments, such as real estate and private equity, in search of higher yields to make up for the system’s growing unfunded liabilities.

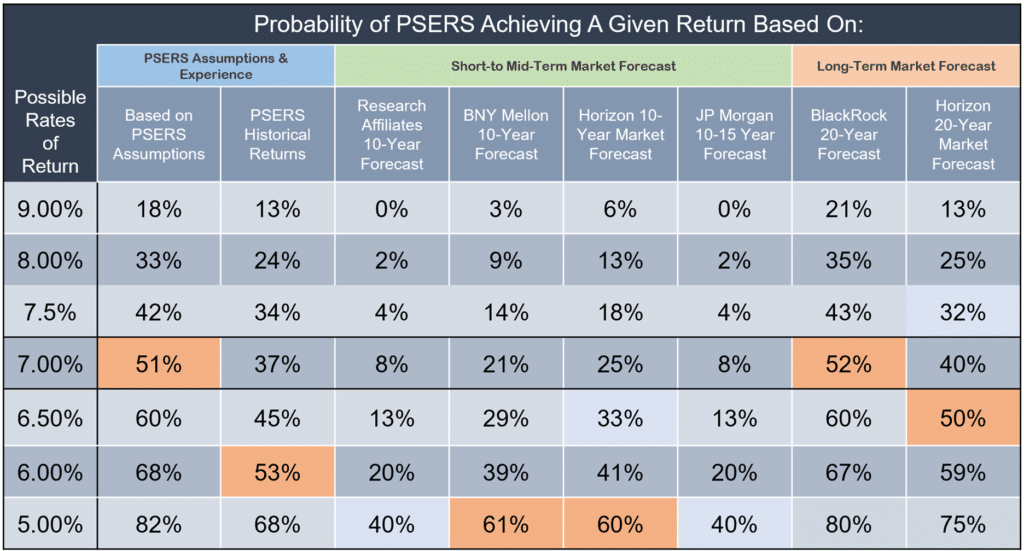

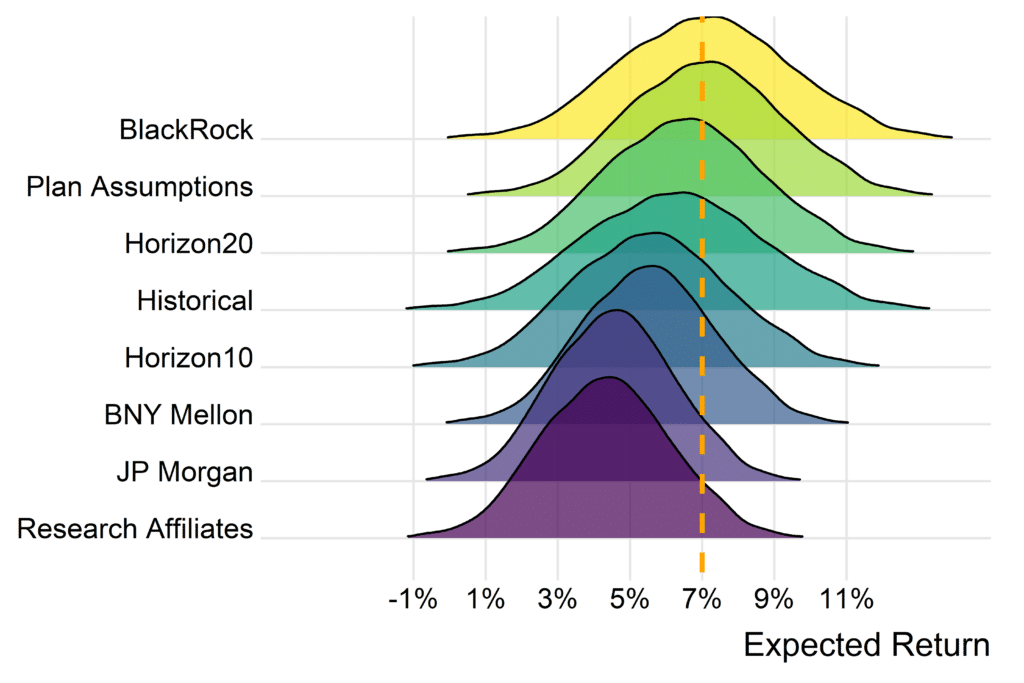

Despite realizing excellent investment returns in 2021, industry capital market forecasts continue to suggest persistently volatile near-term investment returns that stand to only add to over $1 trillion in current pension funding shortfalls. Most near-term investment outlooks we’ve seen from pension boards across the country predict anywhere from a 6.0 percent-6.3 percent return over the next 10 years. PSERS’ assumed rate of return was recently lowered and currently sits at 7 percent.*

These findings suggest that PSERS is not likely to achieve even a 6 percent average return over the next 10-15 years—much less its current assumed return of 7 percent. This suggests there is a high probability that the public pension plan’s unfunded liabilities could get worse, not better, in the near-to-mid term. This underperformance—relative to the plan’s own return rate assumptions—will make the system’s long-term solvency challenges even larger.

Figure 1. Measuring the Probability of PSERS Achieving Various Rates of Return

Figure 2. Differing Investment Return Probability Distributions for PSERS

The results above show only the BlackRock market forecast is anywhere near the current assumed rate of return being used by PSERS, and BlackRock is based on a 20-plus year horizon for which there is little more underlying support rationale than “reversion to the mean,” or put more simply, “a guess that assumes past performance continues,” despite past performance being universally recognized as not being a reliable indicator of future results.

Assumed rates of return are generally set at the 50th percentile, which means the best chance a plan has if they hit every single actuarial and demographic assumption set is a 50/50 chance of achieving long-term solvency. Thus, policymakers should be under no illusion that they can invest their way to solvency alone.

Examining Investment Fees at PSERS

While a few years of good investment performance cannot save a public pension plan, high investment fees combined with underperformance can certainly hurt a plan. Summing external ($2.21 billion) and internal management ($77.4 million) expenses, PSERS reported $2.29 billion in expenses over the past five years. For context, in 2020, the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System reported 36 percent less in total investment fees and expenses than PSERS despite having two times the actuarial value of assets.

High investment fees would not be a concern if these funds sufficiently outperformed assets with lower investment fees. But since the 2008 global financial crisis, they rarely have. For the last five fiscal years, PSERS only outperformed Vanguard’s basic 60/40 stock-bond portfolio (VBIAX), net retail investor fees, once, although it should be noted that both performed well in FY 2021.

Figure 3 shows the two portfolio’s performance over the last five years. Comparing compound annual growth rates, over the past 10 fiscal years shows PSERS returned 8 percent and VBIAX returned 10.3 percent.

Figure 3. PSERS vs Basic Indexed Portfolio (VBIAX) Returns

Using PSERS’ market value of assets and the $2.29 billion in investment fees, we can calculate an average expense ratio of 0.83 percent for the last five fiscal years for which financial reports are available (2016-2020). The expense ratio is the amount paid to investment managers as a percentage of fund assets. If you have $100 in a fund that charged $1 in fees, that would be a one percent expense ratio. Investopedia notes, “a reasonable expense ratio for an actively managed portfolio is about 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent, while an expense ratio greater than 1.5 percent is typically considered high these days.”

Passively managed funds typically charge considerably less. Pension funds, like PSERS, with billions of dollars in assets, can incur even lower costs. Investment professional, Richard Ennis, points out: “Large funds can do [passive investment] for a single basis point [0.01 percent] of expense. The smallest fund in the country can do it at Vanguard for five basis points [0.05 percent].”

Assuming a passive index had approximately the same performance as PSERS and applying an expense ratio of 0.05 percent on the market value of assets, this hypothetical passive investment expense would have totaled $139 million, $2.15 billion less than reported external and internal investment fees over five years. This difference is displayed in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. 5-Year Comparison—PSERS Investment Expenses vs Passive Investment Expenses

The experience of Pennsylvania’s teacher pension system is not all that unusual. An analysis of large U.S. public pensions by researchers Jean-Pierre Aubry and Kevin Wandrei of the Center for Retirement Research found that from 2006 to 2018 the average number of external managers used by plans nearly doubled from 28 to 55, which naturally correlates with higher costs. In the quartile that used the most managers in 2018, this figure jumps to 182 external managers (144 for alternative assets). PSERS lists 176 external investment advising firms in its 2020 annual report.

Whatever combination of active and passive investing trustees choose, they must call to mind that these advisors add costs. Looking at data from 2011 to 2016, Aubry and Crawford revealed three important findings:

- a correlation between higher fees and lower performance;

- alternative investments had higher fees; and

- plans that underperformed their benchmarks had higher expense ratios than plans that outperformed their benchmarks.

Although the plan wisely reduced its assumed rate of return from 7.25 to 7 percent earlier this year, the Monte Carlo analysis shows PSERS’ current rate is still too high. Putting the plan’s assumed rate of return at a lower, more realistic level would, despite a short-term increase in realized liabilities, lower the likelihood of unfunded liabilities accruing in the future. Additionally, lowering the assumed rate of return would reduce the pressure on the plan to engage in aggressive strategies and hire outside investment managers.

PSERS would not be alone in either lowering return assumptions or reducing investment fees. In August, New York State’s Common Retirement Fund announced it will lower its assumed rate of return by nearly a percent. Arkansas, Mississippi, Maine, and others are also making modest reductions to their investment expectations.

On the investment fee side, as Aubry and Wandrei document, several large public pension plans have “recently consolidated their external management team[s] as part of an overall commitment to reduce investment fees, which cut into their after-fee returns.” This year, the North Carolina Retirement System announced it cut $350 million in investment costs over four years after the State Treasurer pledged to cut, a more modest, $100 million.

By further lowering the system’s assumed rate of return and lowering the amount it pays in fees, PSERS can start to forge a pathway to meaningful pension reforms that help keep the promises made to teachers and public school employees and stop accruing pension debt that future taxpayers will be burdened with.

*Correction 10/13/21: The Pennsylvania School Employee Retirement System’s assumed rate of return was lowered from 7.25 percent to 7 percent on August 8th, 2021. This analysis previously stated the plan’s current rate was 7.25 percent. All references to the plan’s assumed rate of return, as well as figures 1 and 2, have been updated to reflect a 7 percent assumed rate of return. Figure 3 has also been updated to reflect PSERS’ latest investment returns, which were reported on 10/08/21. Additionally, fiscal year VBIAX returns no longer include a (~0.07%) downward expense ratio adjustment as further examination suggests this is included with other adjustments (e.g., dividends) in the “adjusted close” data used from Yahoo Finance.