California wrapped up its 2025 legislative session last September, passing 16 new technology bills and signing them into law. As expected in a state that often veers toward heavy-handed regulation, the new laws raise numerous problems and unanswered questions. But at a time when debates about technology are colored by fear, and both major political parties seem to favor regulatory overreach, the new California laws often managed to avoid sweeping mandates and lean toward narrower tools.

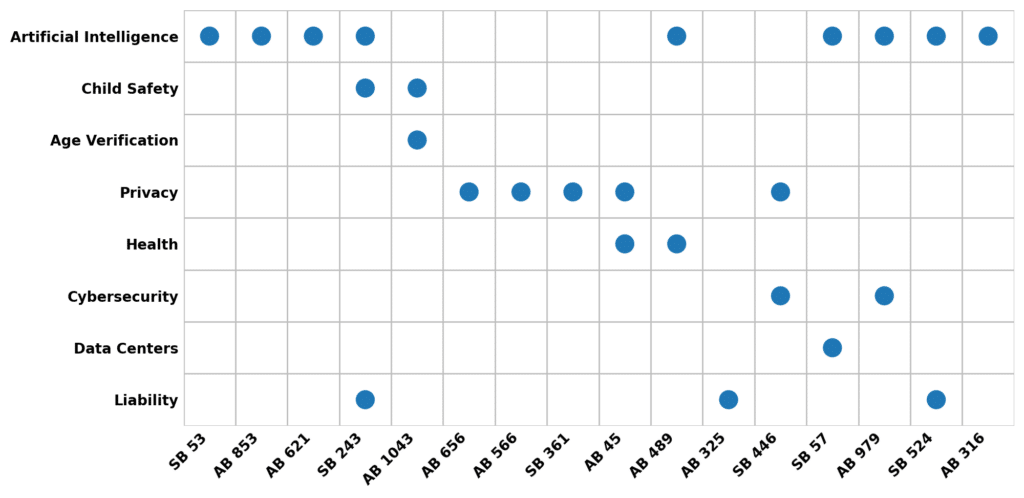

California’s new tech laws by topic area

Artificial intelligence

California passed the Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (Senate Bill 53) after Gov. Gavin Newsom previously vetoed a broader attempt at artificial intelligence (AI) regulation (Senate Bill 1047) in 2024. The law takes a narrower, transparency-focused approach, applying to developers of advanced “frontier” AI models trained using more than 10^26 computing operations. SB 53 requires large developers to publish safety frameworks, issue pre-deployment transparency reports, and notify the Office of Emergency Services of serious safety incidents. The law also adds whistleblower protections and establishes CalCompute, a state-run cloud computing cluster initiative, to expand access to high-performance computing. While critics warn that compliance obligations could favor large firms or devolve into checklist exercises, the law improves on the vetoed SB 1047 and other proposals under debate in the U.S. and Europe by avoiding sweeping mandates.

A separate push for transparency is found in Assembly Bill 853, which expands California’s 2024 AI Transparency Act by requiring platforms generating AI content to preserve provenance data and make it visible to users through platform interfaces. Starting in 2028, it also requires new capture devices (such as webcams, phone cameras, and voice recorders) sold in California to be sold with a hidden label or watermark by default, identifying the device manufacturer and recording when the content is created or altered. The problem is that provenance tagging is still a work in progress, rather than a cross-platform default. Only a handful of devices can embed it today, and it’s unclear whether any video cameras do. Critics fear that AB 853 will prematurely lock in provenance requirements before the technology is settled, leading to an ambiguous standard that will be hard to comply with in practice.

Assembly Bill 621 expands California’s civil liability for nonconsensual, sexually explicit deepfakes and makes it easier for victims to sue not just the creator or uploader, but also certain third parties that keep “deepfake pornography services” operating. The law is notably narrower than the state’s older election-deepfake bills, Assembly Bill 2655 and Assembly Bill 2839, both of which were blocked by federal courts. AB 2655 ran afoul of federal Section 230 protections because it effectively tried to force platforms to police user posts. According to the court, AB 2839 violated the First Amendment because it restricted election-related speech, particularly parody and satire, too broadly. By targeting a concrete abuse category with civil remedies rather than creating speech-policing rules, AB 621 represents a step back from the overreach of earlier efforts aimed at deepfakes.

Age verification and child online safety

Concerns about children using chatbots rose in 2025, with several disturbing stories in the media linking teen self-harm and even suicide to interactions with AI “companions.” California is among the first states to respond with a new law (Senate Bill 243) requiring operators to disclose that a chatbot is not human whenever a reasonable person could mistake it for a human. The law also requires a written protocol to prevent and respond to prompts about suicide or self-harm, including referrals to crisis services like hotlines or text lines. SB 243 attempts to further set guardrails for chatbot users known to be minors, such as default settings reminding users to take a break every three hours and measures to prevent sexually explicit output content. Current fears about kids and AI—some justified, some exaggerated—make new laws aimed at chatbots inevitable. Compared to the massive overreach of federal proposals like Republican Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley’s GUARD Act, effectively an outright ban on chatbot use by minors, SB 243 is a workable path forward.

The Digital Age Assurance Act (Assembly Bill 1043) aims to protect kids online without mandating ID checks that can compromise user privacy and free speech. The law requires parents to declare a minor’s age during device setup, then generates an encrypted age-bracket signal (e.g., under 13, 13-15, 16-17) that apps and services can use for compliance without collecting additional sensitive identity data. Age-verification systems proposed elsewhere incentivize the collection of driver’s licenses, passports, biometrics, or credit-card information to avoid legal liability, something AB 1043 tries to mitigate by barring private lawsuits and placing enforcement in the hands of the state attorney general. Though a meaningful step toward a more privacy-preserving model, California could further strengthen that balance by making the device-level signal optional for parents rather than mandatory.

Privacy

California’s privacy bills passed last year share a clear theme: They aim to facilitate the process of exiting and opting out of services and data collection when users often get stuck. The Account Cancellation Act (Assembly Bill 656) requires large social media platforms to place a clear and conspicuous “Delete Account” button directly in the settings menu, and ties account cancellation to California’s existing right to delete personal information. The Opt Me Out Act (Assembly Bill 566) is a similar mandate for web browsers. Starting in 2027, browsers must include a preference signal that consumers can select to automatically communicate the choice to opt out of the sale or sharing of personal information as they move across websites, but the browsers are shielded from liability if downstream businesses ignore the signal.

Business groups, including the California Chamber of Commerce, opposed AB 566, stating that a browser opt-out signal could disrupt targeted advertising and other ad services. Furthermore, some studies suggest that companies continue to deliver targeted ads even after opt-out signals are sent, making laws like AB 566 ineffective. The problem persists because enforcement is limited, and companies can ignore or narrowly interpret opt-out signals with relatively low risk.

The Defending Californians’ Data Act (Senate Bill 361) takes aim at data brokers—companies that collect and sell personal data without any direct relationship to consumers—by strengthening the state’s broker registry and making its one-stop deletion system harder to ignore. It responds to the reality that brokers can use code to keep deletion instructions out of Google search results, preventing users from exercising their rights.

Health AI and privacy

California’s bills concerning the use of tech in healthcare target location surveillance around care and AI products, borrowing the authority of medical licensure. Assembly Bill 45 restricts how companies use precise location data around health care facilities, limiting the collection and use of precise geolocation near family planning centers and geofencing around in-person health care providers. It also tightens rules on releasing certain health-related research records when requests are tied to the enforcement of other states’ abortion bans. Assembly Bill 489 prohibits AI models from presenting themselves as if a licensed clinician is speaking when no licensed clinician is involved. The goal is to prevent products from borrowing the authority of medical licensure, and the bill avoids the overreach of outright bans passed in states like Illinois.

Other

Assembly Bill 325 makes it easier to sue over suspected price-fixing of any goods and services, especially when rivals use the same “automatic pricing” software and their prices start changing in lockstep. Senate Bill 446 creates clearer deadlines for notifying Californians when a data breach exposes their personal information. Senate Bill 57 asks the Public Utilities Commission to evaluate whether large new data centers could drive up electricity system costs—and whether those costs might be shifted onto other customers. Assembly Bill 979 directs the state cybersecurity office to publish guidance on how government agencies and AI vendors should share threat information and coordinate on security, while also allowing some confidentiality for sensitive vulnerability details.

Additional bills are about keeping responsibility attached to a human, even when AI is doing part of the work. Senate Bill 524 sets rules for AI-assisted police reports: If an officer uses AI to draft or edit a report, the report must clearly say so, identify the tool, and the officer must sign to confirm they reviewed it. Agencies also have to keep the original AI-generated draft and basic records showing how the report was produced. Assembly Bill 316 addresses liability more broadly by preventing defendants from arguing that “the AI did it” to escape responsibility—AI may be involved, but a person or organization still owns the decision to deploy it and the consequences that follow.

Conclusion

There is a clear pattern in last year’s laws: a preference for narrower, more defensible rules, especially where California has already run into vetoes or pushback from courts. SB 53 follows last year’s veto of SB 1047 with a more transparency-focused framework. AB 621, rather than repeating the broad approach of some deepfake bills, focused on clearer, narrower liability. SB 243 adopts targeted disclosure and safety-protocol requirements instead of the more expansive chatbot restrictions in other proposals. It remains to be seen whether this approach persists, but because California’s market size often makes state compliance a national default, the impact of these laws is likely to extend well beyond the state’s borders.