Estimates suggest state-managed public pension systems likely added over $200 billion in additional pension debt in 2020. This increase in debt impacting almost every pension plan in the country is primarily a result of investment return rates failing to meet overly optimistic investment return assumptions set by pension systems.

In fact, the average investment return rate of the 84 state-managed public pension plans that have reported their fiscal year 2019-2020 returns so far is just 3 percent. Despite the stock market having a strong year, Reason Foundation’s analysis shows that the nation’s 10 largest public pension systems averaged just a 2.6 percent rate of investment return, which is significantly short of what the plans were expecting. The shortfalls of these 10 public pension plans account for $68 billion of the estimated $200 billion expected to be added to the nation’s total public pension debt.

Although 3 percent is well above the negative return rate that some experts feared pension plans might see after the pandemic hit, any time that a pension plan’s investment returns fall short of its set assumed rate of return debt is added to the retirement system.

The average assumed rate of return for state-managed public pension plans in 2019 was 7.25 percent. Falling short of that goal by more than 4 percentage points at the aggregate level should be concerning to public employees, plan administrators, and taxpayers alike.

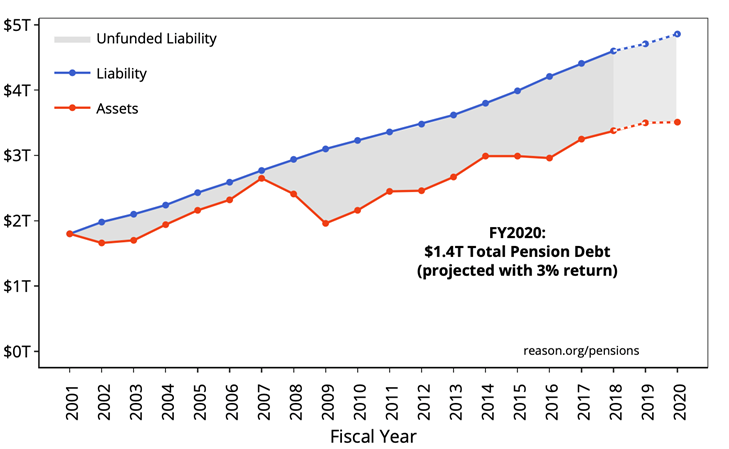

Figure 1 below shows the growth of pension liabilities (promised benefits) vs the growth in pension assets since 2001. The difference between the two, highlighted in gray, is accumulated unfunded liabilities, or pension debt.

Figure 1: Total State-Managed Public Pension Unfunded Liabilities And 2020 Projection

Source: Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation analysis of U.S. public pension actuarial valuation reports and Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs).

One bad year of market returns can significantly impact near-term pension funding. For example, we estimate the New York State and Local Employees Retirement System’s negative 2.7 percent return this year could increase its debt burden by more than $17 billion (based on the market value of assets, see methodology section in the app for more details).

A smaller plan, like the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board, which earned a negative 0.6 percent return, could see a $1 billion increase in unfunded pension liabilities.

While investment performance in any single year may have a relatively limited impact on long-term pension solvency, our analyses demonstrate that consistent investment underperformance relative to the investment return assumptions made by pension systems have been the biggest culprit behind the growth of public pension debt across the nation. Even during a period of strong stock market performance, including the longest bull market in history, public pension plans failed to make significant funding progress as their pension investment results repeatedly failed to match expectations throughout the last decade.

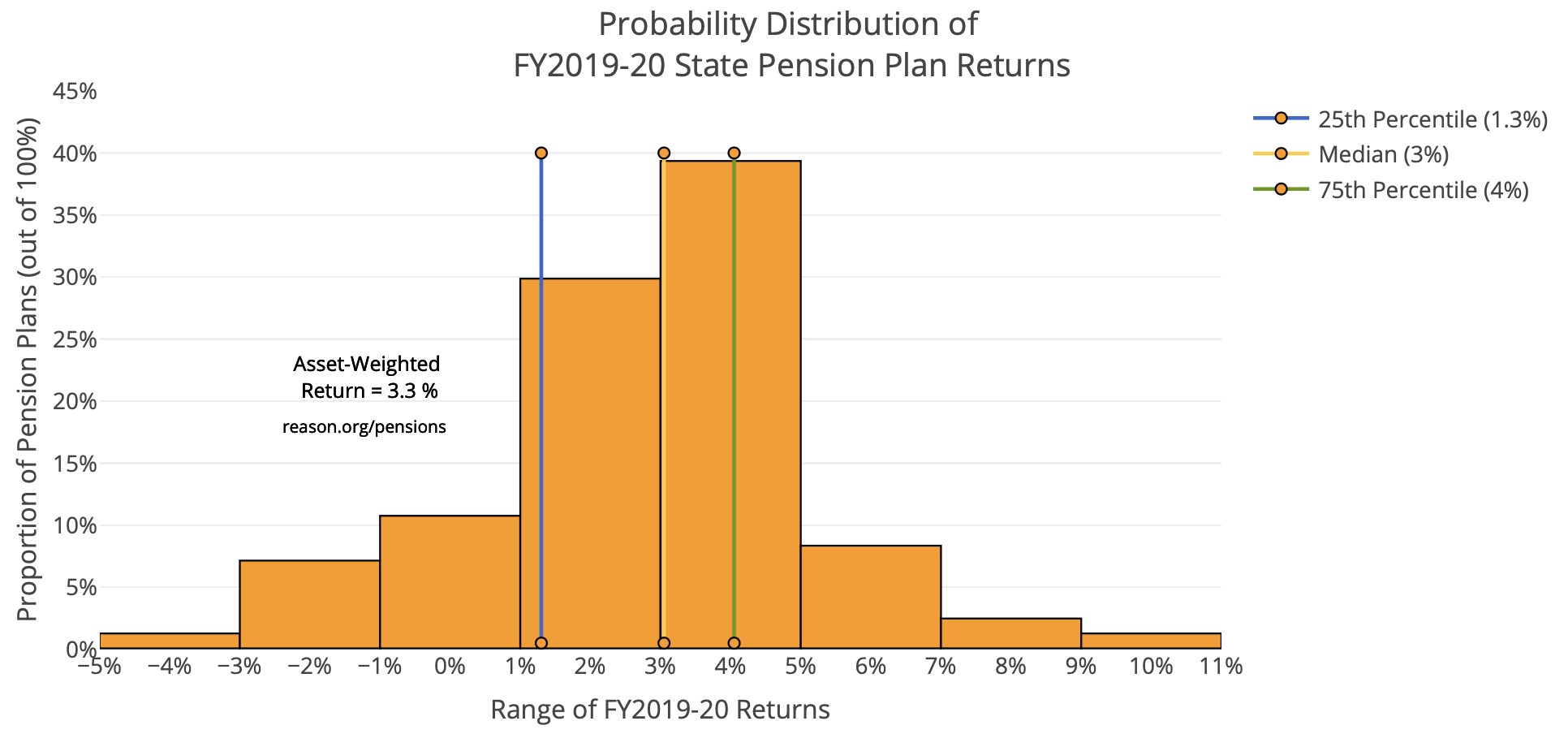

According to Reason Foundation’s analysis, most fiscal year 19-20 investment returns fell within a positive return range of 1.3 percent to 4.0 percent.

Figure 2 below shows that 75 percent of reported returns were under 4.0 percent, 50 percent were below 3 percent and 25 percent were below 1.3 percent.

Figure 2: 2020 Investment Return Distribution

Source: Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation analysis of publicly reported FY20 investment returns,

The worst return so far reported has been the Louisiana State Employees Retirement System, which saw a negative 3.8 percent rate for its fiscal year.

At the other end of the spectrum is the Delaware State Employees’ Pension System, which finished its fiscal year with an impressive 10 percent yield. At the time of this publishing, of the 84 pension systems that have posted complete fiscal year results, only the Delaware State Employees’ Pension System has met its assumed rate of return in FY 19-20.

It’s also worth mentioning that return results for systems with fiscal years ending on Sept. 30 and Dec. 31 will likely look better than the results for pension plans that have fiscal years that ended on June 30, 2020. Markets continued improving in the second half of calendar 2020 after the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and recession so those plans had more time to recover from the pandemic’s initial impact on markets.

Although COVID-19 and the recession’s impact on markets and the economy were less disastrous than many experts had forecasted in the spring of 2020, public pension systems continue to face significant challenges in the years ahead.

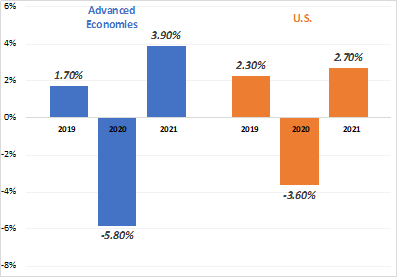

In its latest World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund projects that real gross domestic product (GDP) in the world’s advanced economies will settle at around negative 5.8 percent for 2020 (with the U.S. expected to post a final figure of around negative 3.6 percent) and average 2.2 percent growth rates in the 2022-25 period. The low economic growth forecasts at a minimum portend lower returns on equity investments (e.g. corporate stocks).

Figure 3: Real Gross Domestic Product Growth Projections

Source: International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook October 2020”.

Even before this year’s COVID-19 related market volatility, experts were forecasting a new normal low-yield environment for institutional investors like pension funds over the next 10-15 years. If pension plans and policymakers do not adjust their investment return assumptions to these forecasts, more public pension debt will be added to most systems. As pension assets get more and more depleted, it also becomes more difficult to depend on market returns as a method to climb back to full funding.

The 2020 investment return results add to concerns that public pension plans will continue to struggle with investment return realities that are below the return rates they are counting on, which could have long-lasting negative effects on taxpayers. Long-term underfunding could potentially:

- Increase the risk of pension plans not being able to pay out promised benefits.

- Trigger benefit cuts or much lower benefit accrual formulas for new hires.

- Require future taxpayers to cover high costs for current and past public employees, whose services they will receive no benefit from.

- Pull public funds away from other priorities like K-12 education and public safety.

- Put public pension systems into a “point of no return” where assets are so depleted that it becomes almost impossible to invest their way to full funding, even with double-digit yields later (recent examples include the Puerto Rico, Illinois, and Kentucky pension systems in the last decade).

The first vaccines have arrived but the coronavirus pandemic is not over yet, and states will feel the effects of the COVID-19 recession in their budgets for quite some time. Policymakers should take this unique moment to revise investment return assumptions and other expectations for public pension funds in order to fully-fund pension promises that have been made to workers.