New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy and his transition team wasted no time preparing for the duties of running the Garden State during the transition period. But in the final days of the Christie administration, major developments occurred related to New Jersey’s pension systems that may shape important future debates around one of the most endangered pension systems in the country.

The final report of the Pension and Health Benefit Commission, new legislation that would allow elected officials to re-enter the public employees’ plan, and updated investment return assumptions brought greater attention to New Jersey’s pension crisis last December. Hopefully, the public and the new administration’s focus will stay on reforming the deeply-indebted Garden State’s pension systems.

Final Pension and Health Benefit Commission Report

In 2014, then-Gov. Chris Christie created the New Jersey Pension and Health Benefit Study Commission to “make recommendations regarding the goals and criteria for a sustainable retirement and health benefit system.” Last month, this bipartisan commission released its final report, which briefly outlines the commission’s recommendations to improve the solvency of New Jersey’s health care benefits.

The report focuses on reforming employee health care benefits by making them more comparable with private sector health care benefits, and using the subsequent savings to fund the pension system. Currently, retiree benefits are at “platinum-plus” levels, well above what most in the private sector receive, according to the report.

Based on the current assumptions and methods New Jersey’s retirement plans use, pension and health care costs eat up about 15 percent of the state’s total budget. About $3.3 billion is going to pay-as-you-go (not pre-funded) retiree health care benefits. By 2023, that will increase to a total of 26 percent of the state’s budget, with New Jersey spending about $4.7 billion per year for retiree health care benefits.

What would the savings be if, as the commission suggests, the state were to merely reduce retiree health care benefits to the “gold” level (comparable to benefits with a large private-sector employer)? By making this change and implementing more aggressive cost control measures, the state would have saved $1.4 billion in 2016 and local governments would have saved an additional $2.7 billion. Unlike pension benefits themselves, health care benefits generally have no statutory or constitutional protections and can be modified at the discretion of policymakers.

Despite pension changes in 2010 and 2011—the most substantial of which was a Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) suspension that reduced total liabilities by about $13 billion—the report finds that the rest of the changes (increased contributions, lower pension multipliers, etc.) merely trimmed on the margin and won’t produce substantial savings for decades.

The report also restates previous suggestions such as creating a cash-balance plan for new employees and, after creating a more sustainable plan, including constitutional amendments to guarantee full pension funding over the next 30 years.

The solutions proposed would, even if not fully implemented, likely provide a few shovels to help New Jersey dig out of its current hole. By the same token, even if these changes were made in full, the billions in health care savings won’t be enough to make up the current contribution deficit (almost $3 billion for FY 2018), let alone enough pay for the required contributions under a more realistic valuation of pension benefits (see below). That even these substantial changes wouldn’t save New Jersey’s pensions alone shows how dangerously underfunded and structurally flawed the state’s current retirement benefits are and how desperately bolder solutions are needed to prevent disaster.

PERS Re-Enrollment Bill

A bill, signed by Christie days before his term as governor ended, was passed to change a provision in a 2007 law that put newly-elected officials and some other state employees into a defined contribution (DC) pension plan. The 2007 law required elected officials moving into a different elected office to enter the DC plan, even if they were already part of the Public Employees Retirement System (PERS). The new legislative adjustment will undo this change, allowing members of PERS who changed their elected offices (and thus had to enter the defined contribution plan) to re-enroll in PERS.

Estimates of exactly how many people will benefit from this legislation range from 5 to 50 at most. That several former and current legislators would benefit from the legislation adds some drama to the story, but in the end, this bill will do very little. Only a handful of people will benefit, contributing a negligible amount to the $85 billion liability.

But if the intent of lawmakers who would benefit from the bill is to advance legislation for personal gain, it would be as perplexing as it is shameful. PERS is about 50 percent funded using figures used to determine contribution rates, and closer to 31 percent funded using a more accurate measure of the liabilities.

There’s an obvious appeal to a guaranteed stream of income throughout retirement, and members who left before maximizing their benefits will be getting less than if their pensions hadn’t been frozen. But, on the other hand, why gamble on a system with only 30 cents for each dollar in promised benefits? Either public officials believe that the money will still be there for them when they retire, or they don’t realize the danger PERS and the rest of New Jersey’s pension systems are in. And if the latter is true, then the implications of the passage of this new legislation is far more critical than the fiscal implications for PERS.

Assumption Change

Finally, in December 2017, Treasurer Ford Scudder lowered the assumed rate of investment returns used by the state’s five major pension plans from 7.65 percent to 7 percent. This move, which would bring New Jersey’s assumed rate of return to below the national average of about 7.5 percent, follows the example of other plans that have reduced their assumed rates of return to 7 percent, or even lower.

The immediate effects of this change are twofold. First, the required contribution used to fund state pension plans will increase to account for the lowered expected asset growth from investment returns. If the state were to actually pay the full amount of this increase, then about $390 million would be added to next year’s required contribution rate. But because the state is only set to pay 60 percent of this figure New Jersey is ramping up to make the full required contribution by 2023) it’ll increase the state contribution by $234 million.

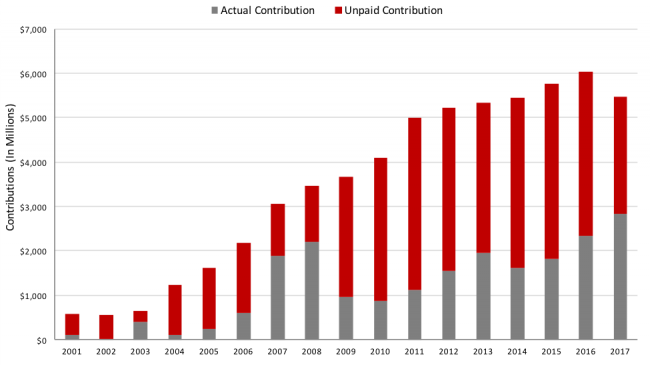

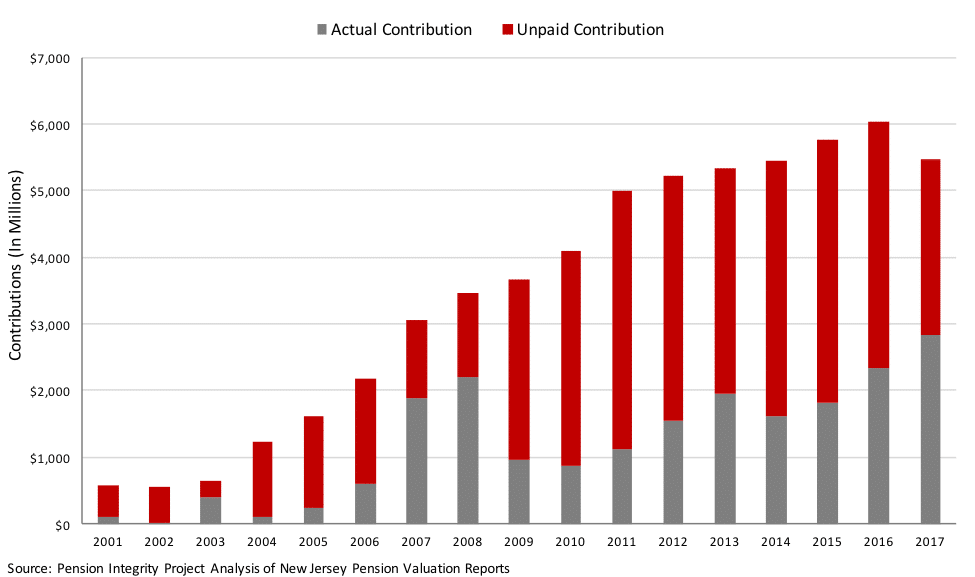

This shortcoming perpetuates a common practice. New Jersey has arguably been most negligent state in the country when it comes to making required contributions. While then-Gov. Christie’s final budget address correctly identified its $2.5 billion contribution as the largest in the state’s history, this is only due to the Garden State’s abysmal pension contribution rate history.

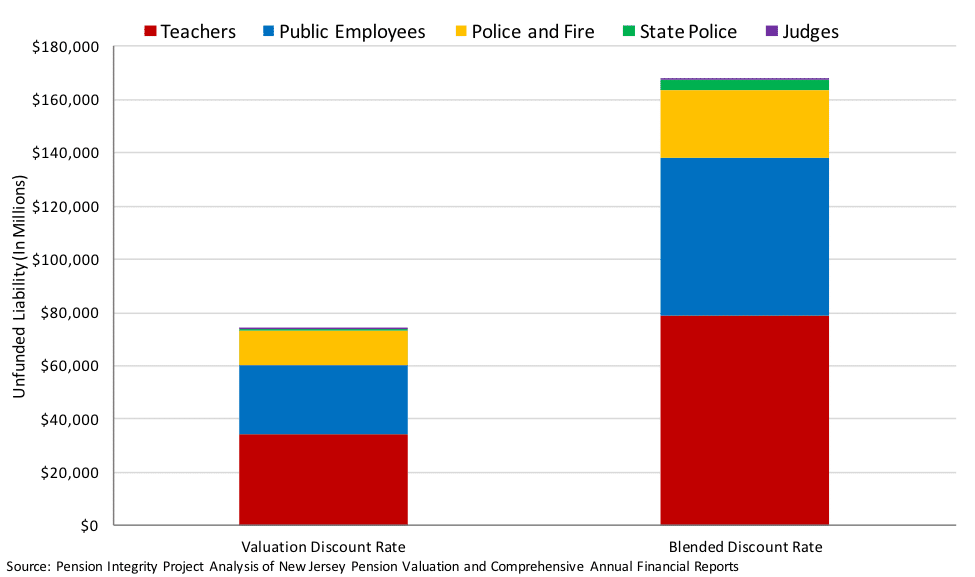

Second, this will lead to a one-time increase in the reported value of New Jersey’s total pension debt, because the assumed rate of return is also used to discount future benefit payments. An increase in the reported value of the plans’ liabilities will lead to an increase in the unfunded liability amortization payment, a component of the state’s contribution. Nothing about the state’s total pension liability has actually changed (there is still a fixed, albeit unknown amount of money that will be paid out over time), just the way it’s measured.

Much like the assumed rate of return, this figure is too high (and shouldn’t be the same as the assumed rate of return in the first place). Thankfully, New Jersey is one of the few states that includes not only a discount rate sensitivity analysis in its valuation reports, but also a valuation using municipal bond yields (see page 36). These rates range from 3.11 percent to 5.55 percent depending on the plan, and this improved methodology, while unfortunately not used when determining the required contribution rates, provides a better picture of what New Jersey’s pension debt actually looks like.

Murphy’s team cried foul after the decision to lower the assumed rate of return, describing it as “playing politics.” But no matter the motivations, the change to the assumed return was a major step in the right direction. This isn’t a policy change; it’s a change for the better with regard to how the state fulfills the promises made to its public sector employees.

Murphy promised to fully fund the pension system on the campaign trail, though he was short on details for where he would find the money. The new (though still overly-optimistic) assumed rate of return will make this promise harder to keep, but if Murphy commits to his policy it will do even more good now that the pension plans are using better assumptions.