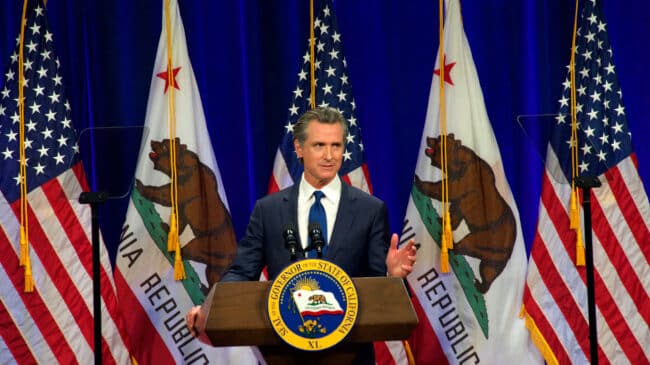

After more than 800 days, California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s declaration of a COVID-19 state of emergency remains in effect. Although Gov. Newsom has dropped most of the restrictions he unilaterally imposed under this emergency, he retains the power to reimpose lockdowns and other highly coercive measures without legislative intervention. The time has come to both end the COVID-19 state of emergency and to reconsider the ability of this or any future California governor to exercise emergency powers indefinitely.

Newsom has employed powers given to the governor under the 1970 California Emergency Services Act—a bipartisan measure signed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan. As amended, the law contains an expansive definition of emergency, which includes “air pollution, fire, flood, storm, epidemic, riot, drought, cyberterrorism, sudden and severe energy shortage, plant or animal infestation or disease, the Governor’s warning of an earthquake or volcanic prediction, or an earthquake, or other conditions.”

Under the law, the state of emergency continues as long as the governor thinks it is appropriate. Or, it can be terminated by a resolution of both houses of the state legislature. According to a March 2022 legislative analysis, 48 states of emergency declarations are currently in force. The oldest, relating to drought and statewide tree mortality, was established by then-Gov. Jerry Brown in Oct. 2015.

Although the COVID-19 state of emergency persists, most of the emergency measures Newsom has taken have expired or terminated, with more declarations sunsetting at the end of this month. While striking down the remaining COVID-19 state of emergency would not immediately free the public from onerous restrictions, it would help protect citizens from further arbitrary use of state authority if the governor decides that the disease spread has become unacceptable.

Some of the public health measures have been arbitrary or even harmful. For example, Gov. Newsom ordered the closure of all state beaches and parks in May 2020, which was highly counterproductive because COVID-19 spreads more readily indoors than outdoors, forcing people to get together indoors rather than at the beach could’ve exacerbated the spread of COVID.

Some emergency orders have been beneficial by relaxing the impact of overly restrictive state laws. For example, one proclamation enables “medical providers to conduct routine and non-emergency medical appointments through telehealth without the risk of being penalized” by “relaxing certain state privacy and security laws for medical providers.” Easing telehealth restrictions has given patients more access to convenient and affordable health care, and the state legislature should make these changes permanent.

Fortunately, the excessive exercise of government power in California has not reached the extremes we have seen in China. As The New York Times admiringly observed in Feb. 2021, “In the year since the coronavirus began its march around the world, China has done what many other countries would not or could not do. With equal measures of coercion and persuasion, it has mobilized its vast Communist Party apparatus to reach deep into the private sector and the broader population in what the country’s leader, Xi Jinping, has called a ‘people’s war; against the pandemic — and won.”

China would eventually experience significant outbreaks, and its oppressive zero-COVID strategy is now an international embarrassment. In Shanghai, the regime of lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, and forced quarantine became a glaring example of tyrannical government overreach.

Thankfully, in the U.S., free expression, democratic procedures, and the Constitution act as a bulwark against China-like abuses of executive power. California’s robust anti-lockdown movement drove a recall election, forcing Gov. Newsom to make his case to voters and modulate some executive actions before being re-elected.

But it’s time for California to learn from this pandemic, further protect individual rights and increase government accountability by altering the Emergency Services Act to automatically sunset states of emergency after a short period, say, 15 or 30 days, unless the legislature votes to extend them. Obliging elected lawmakers to debate and vote on gubernatorial emergency declarations regularly would reinvigorate the state’s tradition of citizen engagement and help prevent future abuses of power.

A version of this column appeared in the Los Angeles Daily News.