The coronavirus pandemic and economic downturn are prompting historic unemployment figures and a lot of uncertainty in the housing market. Homebuilder confidence dropped 42 points in the latest National Association of Homebuilders/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index—the single largest monthly decline in the index’s 35-year history. Low builder confidence could foreshadow a slow-down in new housing construction. Yet, even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, the demand for housing was outstripping supply in several states, including Florida, causing home prices to increase much faster than construction costs.

According to a 2019 report from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, median home prices are more than four times the median household income in several parts of Florida. The problem is especially severe in South Florida, where Miami ranks as the second least-affordable city in the U.S. behind Los Angeles, according to RealtyHop. A state-wide housing shortage means that housing prices are expected to remain high despite the current public health and economic crises.

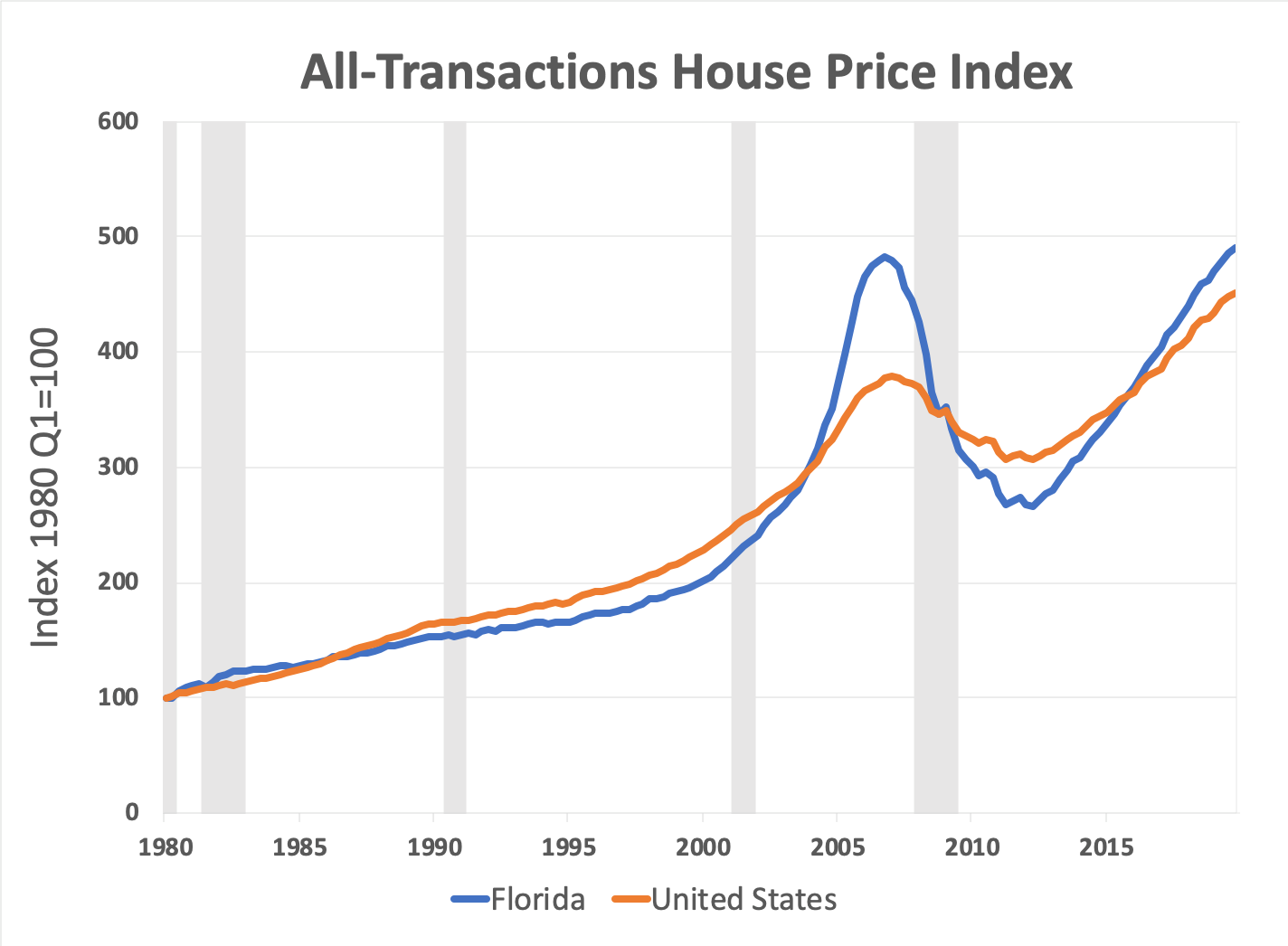

Florida’s housing market was particularly hard-hit by the 2008 financial crisis. In the years leading up to the recession, nominal housing prices in Florida increased by nearly 14 percent annually compared to less than 3 percent between 1983 and 1999. Prices fell dramatically during the recession but have since surpassed the national average and returned to pre-recession levels.

Research from economists Joseph Gyourko and Raven Molloy suggests that the rise in housing prices are due to supply constraints—in the form of restrictive land-use regulations— rather than an increase in construction costs. Lot size minimums, height, and density restrictions, and parking requirements reduce the amount of housing that can be built in a given area. In effect, these regulations increase housing prices by forcing homebuyers to compete over a smaller number of homes than could otherwise be available.

While the number of Florida households increased by nearly 120,000 each year between 2010 and 2018, the housing stock increased by an annual average of 88,665 units—just under 60,000 of which were single-family homes.

Extensive permitting processes lead to delays and increased uncertainty for homebuilders. Permitting delays can be costly because builders often use loans to buy land and building materials, and the payments on those loans need to be made regardless of whether construction is occurring. Those added costs are passed on to buyers in the form of higher home prices.

A recent study published by the James Madison Institute found that the combined effect of land-use regulations and permitting delays were regressive. In other words, regulatory costs were similar regardless of a home’s size but made up a disproportionate percentage of the sales price of smaller homes. If lower-income households tend to purchase smaller, less expensive homes, the costs of regulation and permitting delays would impact them more than wealthy households.

Amid the current crisis, some commenters are suggesting that strict zoning may be desirable as a public health initiative. Residents of lower density, single-family neighborhoods can presumably more easily engage in social distancing, but the relationship between density and the spread of coronavirus is somewhat tenuous. While New York City may be the epicenter of America’s COVID-19 cases, similarly dense cities around the world such as Singapore and Seoul were able to contain the spread by implementing more effective policy responses. A short-term shock like a once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic should not outweigh the long-term economic benefits of higher density development, not to mention the measurable health benefits associated with higher density development during normal times.

Rolling back restrictive land-use regulations can help alleviate Florida’s growing housing shortage, which could become worse if builders remain pessimistic about the economy and further reduce construction. Moreover, state and local lawmakers should work to expedite permitting processes to reduce uncertainty and get more Floridians back to work as quickly as possible. The economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic will likely be long-lasting, but allowing more flexibility in the housing market could provide some financial relief by way of lower housing costs.