In December 2020, half a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) received a call from the U.S. Department of the Treasury. For years, the U.S. had accused Switzerland of monetarily steering the franc (CHF) to create “unfair” advantages that harmed its international trading partners. Swiss officials were informed that they were designated a “currency manipulator.” The reason: SNB had gone too far dampening the appreciation of the franc to keep inflation down.

The U.S. dollar appreciated substantially during the pandemic, as individuals, corporations, and governments worldwide flocked to it as a safe haven. The Swiss franc did as well.

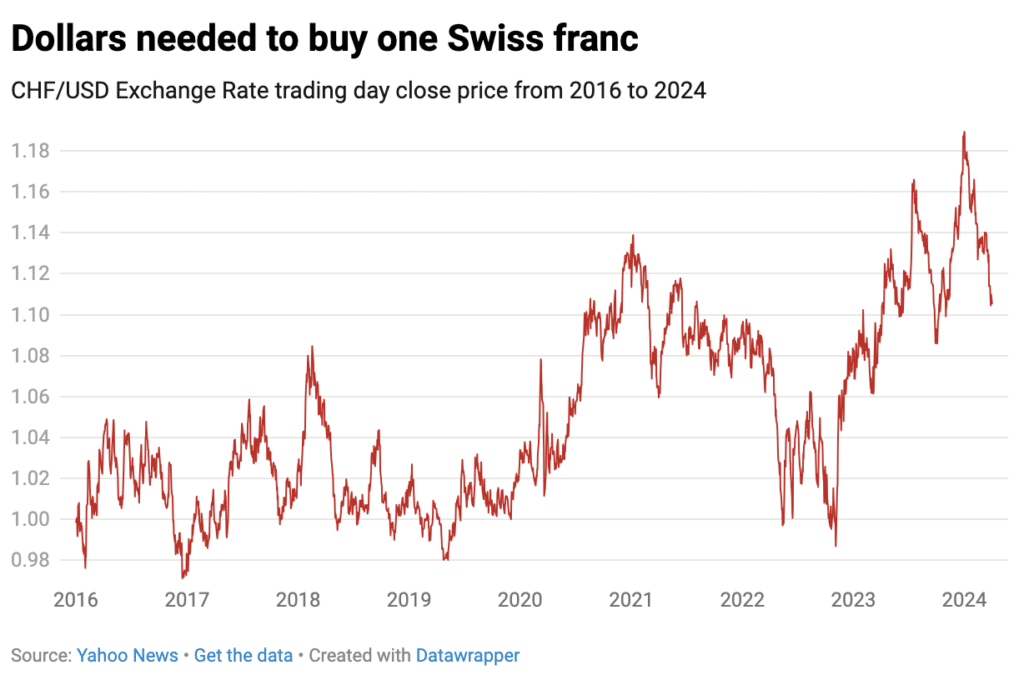

USD to purchase 1 CHF, with currency manipulator watchlist period (Dec 2020 – June 2023)

The surge in demand led to a sharp increase in the franc’s value against other currencies, including the dollar, as shown above (inverted). The exchange rate rose sharply in this period, from around $1 at the start of 2019 to a peak of $1.14 in December 2020 —even though at the same time, the SNB was exchanging francs for over $98 billion worth of foreign assets to prevent the appreciation of the domestic currency. That was right before the US Treasury called.

The “currency manipulation” designation

Twice a year, the U.S. Treasury releases the “Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners” report, analyzing trends in exchange rates, monetary policy, and the balance of payments among major U.S. trading partners.

When deciding whether to slap the “currency manipulator” label on a foreign nation, the Treasury Department first considers whether the country has:

- A bilateral trade surplus of at least $15 billion with the U.S.

- Foreign currency interventions higher than 2 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP)

- Material current account surplus exceeding 3 percent of GDP

Because Switzerland breached all three of these criteria, the U.S. Treasury classified it as a currency manipulator.

According to the December 2020 edition of the Treasury report, Switzerland had been running an “extremely large current account surplus,” and the bilateral trade deficit had “widened notably over the last year reaching $49 billion over the four quarters through June 2020.” Further, the Treasury pointed out that SNB had purchased $103 billion —14 percent of Swiss GDP — of foreign assets to prevent exchange-rate appreciation between July 2019 and June 2020. Of that, $93 billion was disbursed in the first half of 2020 alone.

The Treasury’s demand: let the franc’s exchange rate run its course, accept inflation domestically, and contend with the gains and losses of exchange rate fluctuations. The report castigated what it characterizes as Switzerland’s “reliance on unconventional monetary policy” to support its price levels.

Unique circumstances

Switzerland is among the few countries on its continent that does not use the Euro. Switzerland’s population of only 8 million people makes the franc the 84th most-used currency in the world — compared to 350 million people using the Euro. Why is the franc, backed by such a tiny user base and economy, trusted by so many?

The source of the Swiss franc’s comparative advantage has historically been twofold: it serves as a path to bank secrecy and has functioned admirably in the monetary function of a store of value. Geneva’s reputation for discretion — which dates back to the 18th century — made the city and its banks a desirable destination for wealthy individuals of all stripes, from princes and pontiffs to industrialists and mercenaries. However, over the last decade, American authorities have become concerned that Swiss discretion was enabling high net-worth tax evasion and allowing the proceeds of large-scale crime to be hidden from tax, regulatory, and intelligence agencies outside of Switzerland. This led to an international effort to end Swiss banking secrecy and consequently, according to the Swiss Bankers Association, “there is no longer Swiss bank client confidentiality for clients abroad.”

Bank secrecy is dead, but the franc is very much alive. Despite international pressure to change Switzerland’s long-observed banking privacy standards, the purchasing power of the currency has remained relatively stable. The SNB has a well-documented history of being ruthless in fighting inflation — not merely as a matter of principle, but rather of survival. As a small, landlocked, and mountainous country, Switzerland can scarcely afford price inflation: maintaining a constant flow of international capital depends on the expectations for low inflation and stable exchange rates.

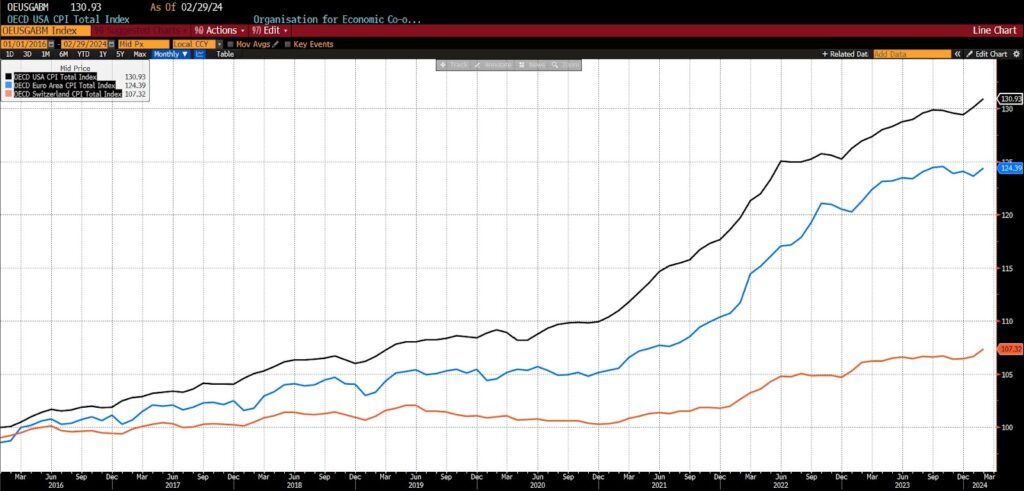

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Consumer Price Indices

The role of the Swiss franc, like gold, U.S. dollars, and U.S. Treasury securities, is that of a safe haven asset; one in which banks, institutions, and high-net-worth individuals seek shelter during emergencies or periods of elevated uncertainty. Although the banking confidentiality that historically attracted the rich to Swiss banks has been abolished, the franc has remained a safe-haven alternative to the dollar, especially in periods of above-average inflation or geopolitical tensions.

The importance of stability for the appeal of the franc also means that SNB faces a paradox: the more stable (especially inflation-resistant) a currency is, the greater the demand for it, which creates volatility and undermines the alluring stability. That phenomenon is particularly acute in the case of Switzerland owing to its size (its population is smaller than that of Chicago), which makes it difficult to absorb the effects of disproportionate foreign demand for its currency. Swiss central bankers have thus found ways to make the franc relatively less attractive, especially during acute demand. To do this, they frequently rely on foreign asset purchases — which push francs into the global foreign exchange markets and devalue exchange rates. Switzerland has also been known to employ negative nominal rates to dampen long-term foreign investment and increase both the supply and velocity of francs domestically.

At the outset of the pandemic in 2020, billions of dollars, euros, and yen were exchanged for Swiss francs. SNB suddenly found itself in need of aggressive interventionary measures to keep the exchange rate stable. The Swiss franc is a managed-floating currency, and the SNB sets monetary policy in an effort to stabilize purchasing power. But in times of profound regional and global risk, large foreign inflows put considerable appreciation pressure on the franc, the sustained appreciation of which may contribute to domestic inflation.

In explaining why it decided to label Switzerland a currency manipulator, the U.S. Treasury poked at the country’s “reliance on unconventional monetary policy.” Yet Swiss monetary policy is unconventional because it has to be. SNB’s balance sheet is tiny compared to most other central banks in the world and is largely accounted for by holdings of Swiss government securities, gold, and some foreign obligations — all of which are reflective of the country’s culture of fiscal discipline. So, when the franc’s exchange rate is shocked, as it frequently is, by increases in its demand, its central bankers have to get creative, relying upon abrupt policy rate changes and foreign asset purchases/sales to dampen exchange rate volatility and inflation.

Though the foreign purchases were primarily responsible for the franc’s general stability, without the negative interest rates imposed between 2015 and 2022, Switzerland’s central bank would have needed to spend as much as $630 billion more during the same period to reach the inflation and exchange-rate levels.

Under the Treasury microscope

There are no official or immediate consequences for being labeled a currency manipulator by the Department of the Treasury. That does not mean, however, that there are no risks associated with being put on the list. Inclusion can signal elevated chances of retaliation from the United States. And mere possibility of trade or capital restrictions can frighten investors and depositors away from the country, making being titled a manipulator, even if undeservedly, a genuine concern.

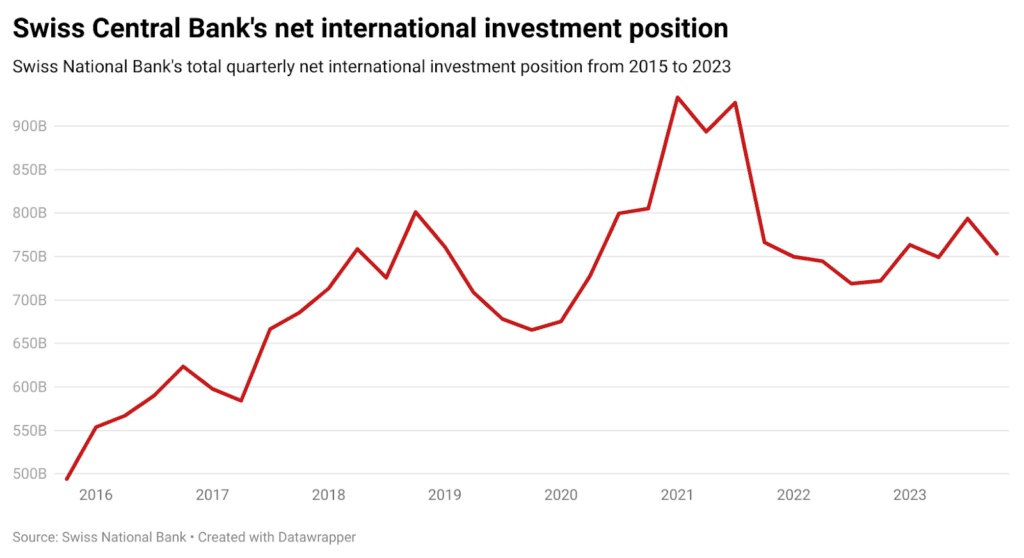

So in response to U.S. warnings, Switzerland’s central bank complied. It allowed the franc to weaken and inflation to emerge within its borders. As shown above, SNB’s net international investment position grew every year from 2015 to 2021, at which point it began to drop sharply. In 2022, Switzerland sold $22.8 billion in foreign exchange, a significant change from the $23.0 billion in net purchases it undertook throughout 2021. And, as is observable in the first chart, the exchange rate has risen significantly. In December 2023, for the first time in more than a decade, the CHF USD exchange rate reached $1.18. As of this writing, it hovers around $1.10.

Switzerland was removed from the Treasury’s currency manipulator watchlist on April 2021, as it no longer met all 3 criteria outlined by the department but it remained on the Treasury’s “Monitoring List” until the most recent report, exonerated in November 2023 for only meeting one of the criteria —capital account surpluses.

Prodded by the U.S., SNB has entered a new era. In early 2023, the Swiss central bank abandoned its nearly eight-year policy of negative interest rates to fight resurgent inflation, which reached a 29-year high in August 2023. Reducing foreign exchange purchases, Swiss monetary policy is likely to appear more conventional from now on.

The decision to place Switzerland on the currency manipulator list was driven by the belief, among U.S. authorities, that because Switzerland exports much more than it imports from the U.S., its efforts to keep its exchange rate below market would make its exports cheaper artificially, thus giving Swiss producers an unfair advantage over American manufacturing interests. (Although rarely used of late, the U.S. Treasury reserves the right to intervene in foreign exchange markets to benefit the dollar at its sole discretion.)

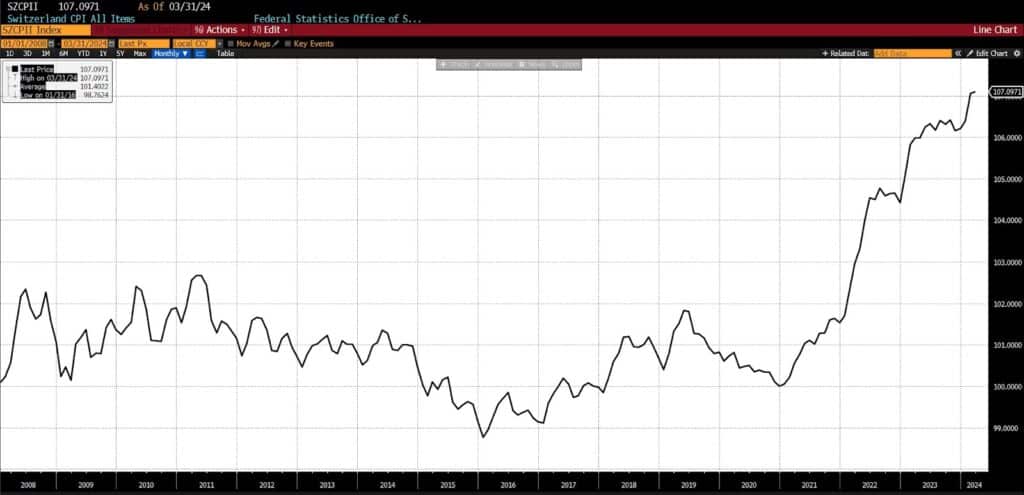

And so U.S. manufacturers are getting a leg up, while Swiss citizens are contending with the highest inflation in the country’s history. The rise in the Swiss general price level is not nearly as high as the rest of the world has experienced over the past three years but is elevated significantly nevertheless.

Switzerland CPI, All Items (2008 – present)

The recent trend toward de-dollarization has roots not only in the weaponization of the dollar’s reserve currency status and Federal Reserve policy errors but in an increasing incidence of exchange rate coercion. Beneath the rhetoric is mercantilism, albeit of a sophisticated stripe. Swiss, and world (Vietnamese, et al) central bankers are told that their domestic monetary policy obligations, primarily consisting of maintaining stable price levels and smoothing economic cycles, must be balanced with or even subjugated to currency management practices that accommodate American exporters and competitors more broadly. The U.S. Treasury does not appreciate Switzerland, or any other nation, stepping on the U.S. dollar’s toes. To keep the Swiss franc viable as an alternative safe haven to the dollar, the SNB must travel a winding and sometimes unpredictable policy path between attracting foreign investment, fostering a stable domestic economy, and appeasing American monetary hegemony.

A version of this article first appeared at the American Institute for Economic Research.