The city of Harvey, Illinois, announced the layoffs of 40 police officers and firefighters last April. The cuts were a devastating blow to the city, as the departing employees represented nearly half of Harvey’s public safety workers. Unsurprisingly, unmanageable pension liabilities were the catalyst behind the layoffs. What makes Harvey’s crisis of particular interest, however, is that the current situation is connected to a statewide policy — passed in 2011 and enacted in 2016 — that set the stage for state intervention in extreme cases of municipal pension mismanagement.

Seven years ago, Illinois passed Public Act 96-1495, which allowed the state comptroller to act if there is evidence that a local government is not making its required pension contributions to police and firefighter plans. In such situations, the comptroller is supposed to hold tax money that would normally go from the state to the local government and to instead apply all of those funds directly to the city’s pension fund. The purpose of the law is to protect public safety employees from any irresponsible underfunding of their retirement fund.

Although the law passed in 2011, it did not take effect until 2016. This is the first example in which the state’s comptroller has deemed it necessary to intervene according to the law. After racking up an unfunded liability of $36.7 million and a funded ratio of 29 percent from years of underpayment to the pension, Harvey’s Police Pension Plan sued its own local government sponsor. This action set the 2011 law into effect, resulting in the state’s comptroller garnishing $1.5 million in state tax revenues that was scheduled to go to the town.

After a reactionary legal appeal, a judge ruled that the comptroller was acting within their rights according to the law. Unable to cover payroll expenses, Harvey officials announced the layoff of nearly half its public safety workers the day after the court ruling.

According to representatives of the police pension fund, a deal with the state was in the works to split the garnished funds to the town and the pension, but a new claim against the town from the Harvey Firefighters’ Pension Fund—which is $67.6 million underfunded with a shocking 12 percent funded ratio—derailed these arrangements, forcing the comptroller’s hand to carry out the garnishment. Finally, just last week the city reached an agreement with the comptroller, which granted them access to a portion of the garnished revenue. This provides some temporary relief to Harvey but future funds will continue to be held and redirected by the state’s comptroller.

The case of Harvey appears to be the canary in the coal mine, as more than 200 other municipalities in Illinois also face the real possibility of seeing revenue intercepted according to the 2011 law. North Chicago has already become the second city to join Harvey. After confirming the city’s inability to pay its required pension contribution, the Illinois comptroller has begun intercepting payments meant to go to North Chicago so they can be applied instead to the city’s pension fund. Judging by the poor health of many of the state’s local pension plans, it is likely that more are to follow.

In response to the growing pressure from the 2011 law, lawmakers are proposing legislation that would delay any garnishment of funds until 2020 and add exceptions to the law for municipalities that face fiscal hardship. Many, however, believe that this proposed bill is just another example of kicking the can down the road, as it allows local governments to continue underfunding their pension plans.

All of these recent local developments in Illinois illustrate a growing problem that more and more governments around the country are facing. How can states promote or enforce responsible funding of municipal pension plans? This question is becoming increasingly relevant, as policymakers are exploring ways to protect local government workers from pension insolvency and degraded retirement security, which comes as the result of irresponsible pension management in some localities. Reason’s Pension Integrity Project has promoted transparency standards for local governments in Michigan for this very purpose.

Another relevant question in need of an answer concerns the proper balance between protecting local workers and protecting local governments when dealing with municipalities that have become delinquent in their pension payments?

Harvey’s current woes illustrate the challenges of trying to achieve such a balance. The 2011 law was passed to protect the pensions of local workers, but in this case, it will be enforced at a great cost to the town’s ability to serve its citizens. But exploring the recent history of pension funding policy used by Harvey’s policymakers offers some relevant context regarding who should be bearing the burden of responsibility.

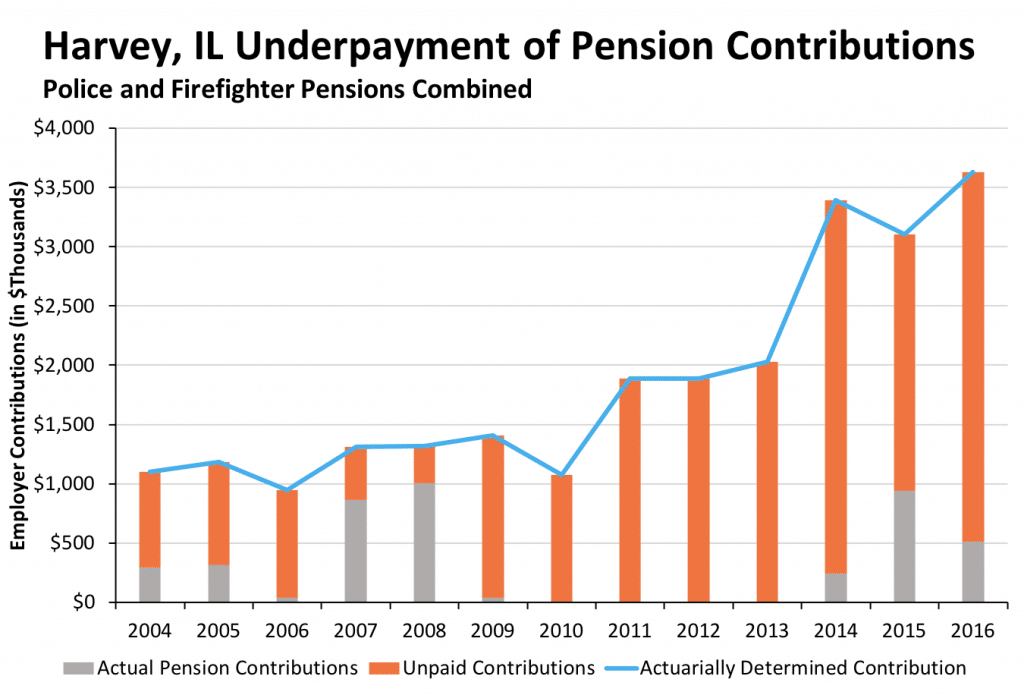

The Harvey pension plans are suffering significantly from what can only be described as extreme underpayments of annual contributions. The police pension fund has received contributions well below the required amount ever since the 2008 market downturn. The town’s firefighters’ fund has seen even worse underfunding, with severe underpayment going back to 2004 (thus, the poor funding policy predates the economic hardships of 2008). Both plans combined, the town has shorted its contributions by a total of $20 million since 2004, even going three years — 2011 through 2013 — without dedicating a single dollar to either fund.

One way to look at these underpayments is to assume those amounts were instead used towards the payrolls of the town’s public safety workers, especially in the context of the recent layoffs of these workers. Using payroll and active member numbers from their financial documents, the amounts presumably diverted to employees was enough to pay about 5 police officers and 17 firefighters from 2004 to 2016, which is about 9 percent and 36 percent of the current staffs respectively. In other words, the town was in a situation where it needed to cut back on services in order to keep its pension promises to current and past workers. Instead, it consistently shorted the required annual contributions.

Viewed in this light, the mass layoffs this year are perhaps unsurprising, as the town needed to cut services and/or increase revenue to address this challenge years ago. What is striking is that Harvey likely would have continued to short its payments to the pension fund at the expense of its employees’ retirement security, save the recent interventions from the state comptroller.

The situation in Harvey demonstrates the complexity of balancing responsibility between state and local governments. Illinois’ 2011 legislation may appear to be a heavy-handed response to municipalities who are struggling to keep up with the rising costs of pensions, but—at least in the case of Harvey—it does maintain a system in which the consequences for poor funding policies falls onto the responsible party. That is little consolation, however, to the citizens of Harvey who will see large cuts in crucial services from no direct fault of their own.