Due to a brewing pension crisis, the City of Fort Worth, Texas and its public workers face a critical decision in the coming months that will have far-reaching impacts on workers and taxpayers alike.

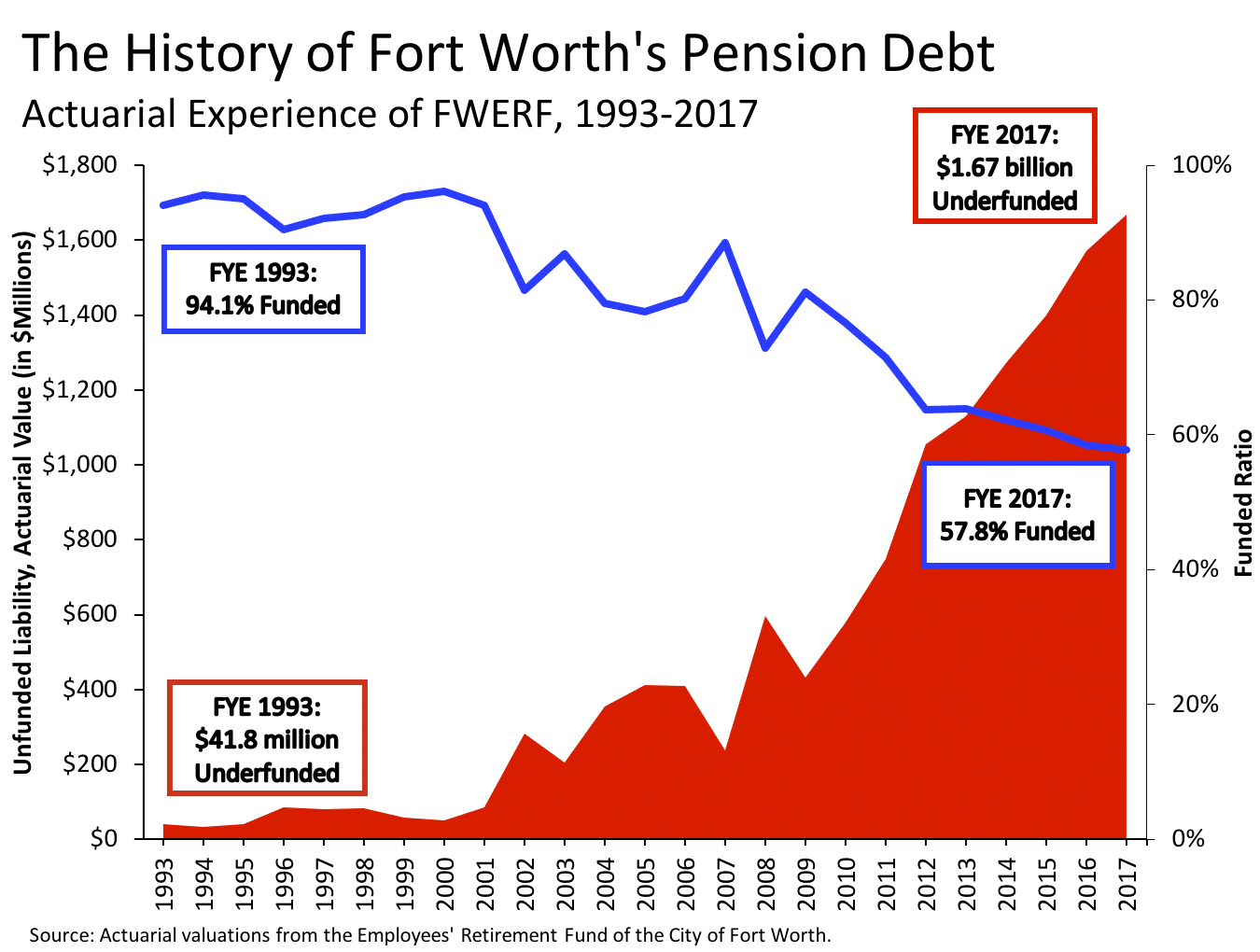

The Fort Worth Employees’ Retirement Fund (FWERF)—the city’s pension plan for police officers, firefighters, and general employees—faces a $1.6 billion shortfall in promised retirement benefits. Not only is the plan well beyond the standard 30-year amortization period to pay off its unfunded liabilities, but it is also estimated to run out of money by 2048 using its current investment return assumption. If the plan experiences lower than expected long-term market returns, it could face depletion as early as 2037.

Needless to say, Fort Worth’s leaders will need to make major reforms to the plan if it is to fulfill the promises made to the city’s 6,200 active employees and 4,200 retirees. Last month, the city manager presented several proposals for increasing contributions and reducing plan liabilities to the city council. These include an increase in city contributions, changes to benefits and retirement eligibility, and an increase in employee contributions.

The council was expected to vote on a final proposal on Sept.18, but the decision was postponed after the tragic death of a Fort Worth police officer. Due to the critical status of the plan and its importance to the community, it is likely that the vote will be rescheduled soon. If a proposal passes, the employees of Fort Worth will hold a vote on it in November.

The reform will not pass unless it receives positive votes from a majority of all employees, which is a high hurdle to overcome considering employee associations have already voiced their disapproval. If no reform is passed, the state government will likely need to intervene, as it did with Dallas’ and Houston’s recent reforms.

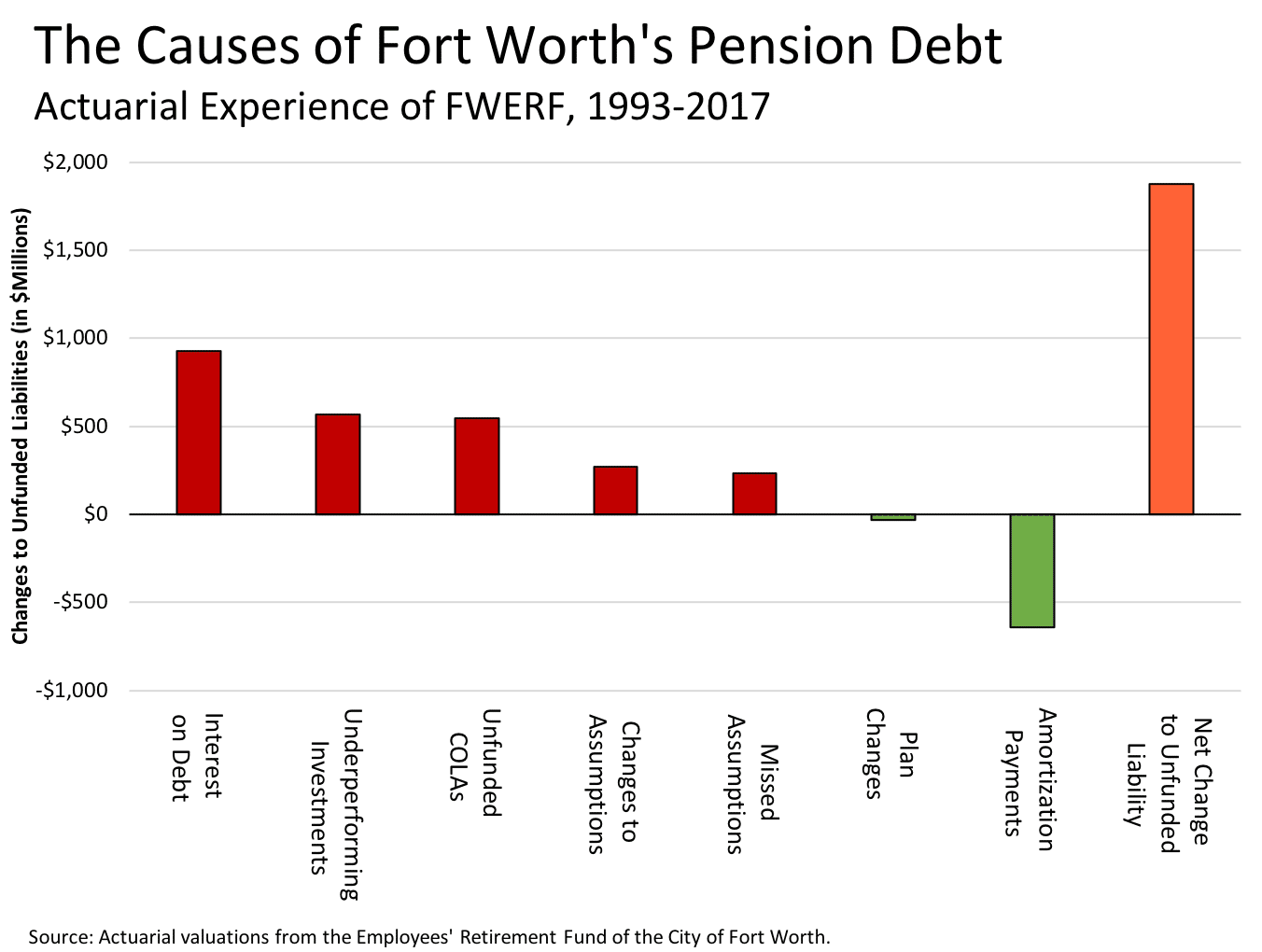

As various reform proposals are formulated in Fort Worth over the following months, it is useful to focus not just on the current liability and asset values, but also on the individual factors that contributed to the current $1.6 billion in unfunded liabilities. Using data collected from FWERF annual actuarial valuation reports going back to 1993, it becomes apparent that the plan’s current woes are the result of a variety of issues.

FWERF has held an unfunded liability—meaning the value of the plan’s assets has been below the present value of the projected benefits to be paid—since before 1993. The figure above demonstrates that several factors have added to this growing unfunded liability since that time.

According to actuarial reports, the largest contributor to FWERF’s current issues is interest on the debt, adding $927 million to the unfunded liability since 1993. This demonstrates a common problem found in many other pension plans around the country, where annual contributions made by employers toward pension debt amortization payments are insufficient to even cover the interest on the debt (so-called “negative amortization”), much less pay down unfunded liabilities. Much like any other kind of debt, holding an unfunded liability can become very costly, especially for plans like FWERF that suffer from extremely low funding. Solving this problem requires establishing a more conservative funding policy designed to pay down pension debt and achieve 100 percent funding as soon as possible.

The next largest issue for FWERF is underperforming investments, which demonstrates the harm that has come to the plan from unrealistic expectations on investment returns. The plan has used a 7.75 percent assumed rate of return since 2016, but that figure has ranged as high as 8.5 percent as recently as 2010. By contrast, FWERF reports show that the plan has achieved an average of just 4.75 percent in returns over the past decade. Achieving lower than expected returns results in under calculation of contributions, which has added $658 million to the plan’s unfunded liability since 1993.

Correcting this particular issue is critical, but can be difficult. Lowering the assumed rate of return doesn’t necessarily create more liability for a plan, but it does lead to recognizing actual liabilities that were previously unrecognized. On paper, lowering the assumed rate will result in an increased unfunded liability, which would then be reflected in the above chart’s depiction of “Changes to Assumptions.”

Most importantly, a more realistic assumption for future returns would increase required contributions into the plan, which would lower the long-term costs caused by carrying the debt and reduce the likelihood of future underperformance. In short, lowering the assumed rate of return to more realistic levels leads to the recognition of more debt and higher future annual contributions into the pension plan, even as it helps de-risk the plan for the future. While this change in policy may be difficult to sell to some interested parties, the above analysis shows that it ought to be among the top priorities for Fort Worth.

According to FWERF’s actuarial documents, the addition of an ad-hoc cost of living adjustment (COLA) benefit in 2007 ended up adding a significant amount to the liability, resulting in a $549 million growth in unfunded liabilities. Added benefits like this can be liability-neutral if they are properly funded, but in this case, the city council added the benefit without providing any form of pre-funding. According to a 2014 Actuarial Valuation, “liabilities are calculated assuming that no ad-hoc COLAs are payable in the future, and past practice has been to include the impact of the COLA in the year in which it is paid.” In other words, rather than being properly pre-funded, the annual impact of the COLAs went directly to the growing unfunded liabilities.

Other missed economic and demographic assumptions—assumptions other than investment returns—have added a smaller, but still notable, amount to FWERF’s current unfunded liability. These assumptions include mortality rates, pay increases, and other actuarial projections. Actual experience differing from these assumptions added $236 million to the plan’s unfunded liability since 1993. To counter this problem from past experiences, policymakers could consider more frequent adjustment and more conservative assumptions in the future.

Breaking down the growth of FWERF’s current unfunded liability shows that Fort Worth’s pension issues stem from many contributing factors. The city’s first proposal for reform includes measures to increase contributions to the plan as well as steps to reduce future liabilities, including significant changes to the COLA. These are both crucial steps for the future retirement security of public workers in Fort Worth. They begin to address the biggest current cause of the problem—interest on the debt—and increase amortization payments to counter the growing pension debt.

But these are not sufficient; stakeholders and policymakers involved in the process must also take a look at addressing the other factors that have contributed to FWERF’s unfunded liability. Namely, they ought to consider adopting more conservative actuarial assumptions, reducing the financial risks around the retirement options offered to public workers, and ensuring that the benefits offered to future workers are able to be sustainably funded for the long term, unlike the current situation. Failing to address these aspects of the current situation risks treating the symptoms while ignoring the causes of Fort Worth’s pension problems.