Legislation looking to make the Teacher Retirement System (TRS) of Texas actuarially sound is making its way through the Texas Legislature. As the state’s largest public system, TRS oversees the retirement benefits of nearly 1.6 million active and retired educators and is currently in great need of additional funding.

In the fall of 2018, the TRS Board of Trustees voted—at the advice of plan actuaries—to lower the system’s assumed rate of return from 8 percent to 7.25 percent. This move was a necessary step as market returns since the 2008 recession have proven to be significantly lower than in previous decades. The change exposed hidden pension costs and pushed TRS outside the Pension Review Board (PRB) definition of actuarially sound.

In other words, the cost of the pension plan is proving to be more expensive than previously anticipated, and higher annual contributions will be necessary to fully fund the retirement benefits that have been promised to Texas teachers.

The Senate’s approach to getting TRS back to being actuarily sound—Senate Bill 12, which was passed by the Senate in March—turns to the state, school districts and teachers alike to close the gap in needed contributions by raising TRS contribution rates on the three central stakeholders over the next five years.

The House has since amended SB 12 to place the burden of increased contributions entirely on the state. Both versions of the reform involve gradually increasing the total annual contributions into the system by about 2 percent. The infusion of additional cash is estimated to allow TRS to pay off its unfunded liabilities within 30 years rather than the current 87 years. Shortening the amount of time it takes TRS to pay off its debts to 30 years is particularly important as it directly affects the state’s ability to provide annual cost of living adjustments (COLAs), which retired teachers have gone without for six consecutive years.

Another element of the Senate approach provided a one-time, state-funded bonus payment of up to $500 while the House version provided up to $2,400 for each retiree. In both cases, the money for the one-time payment will come from sources outside of TRS and will have no effect on the system’s liabilities.

An actuarial analysis of the Senate’s approach suggests that the increased contributions, while expensive, are likely to make a significant difference in the pension’s long-term sustainability.

Figure 1 illustrates the increased annual employer contributions as proposed by the Senate. The Reason Foundation Pension Integrity Project’s actuarial analysis indicates the Senate’s reform would cost the state—or the taxpayers—nearly $22 billion over the next 30 years.

The House amended version of the bill, which has the state paying the entire share of the increase in contributions, would obviously lead to employer contributions exceeding those in the Senate version.

Figure 2 shows that the state can expect to pay nearly $26 billion more into the TRS fund over the next 30 years if the final bill is passed as the House amended.

The overall effect on TRS funding between the two versions of the bill would be close to identical under either Senate of House proposal since they both increase the total contributions into the plan by about 2 percent.

In return for the added costs, increased contributions appear to make a major difference in the system’s projected fiscal health by prompting significant shifts in the trajectory of key plan indicators.

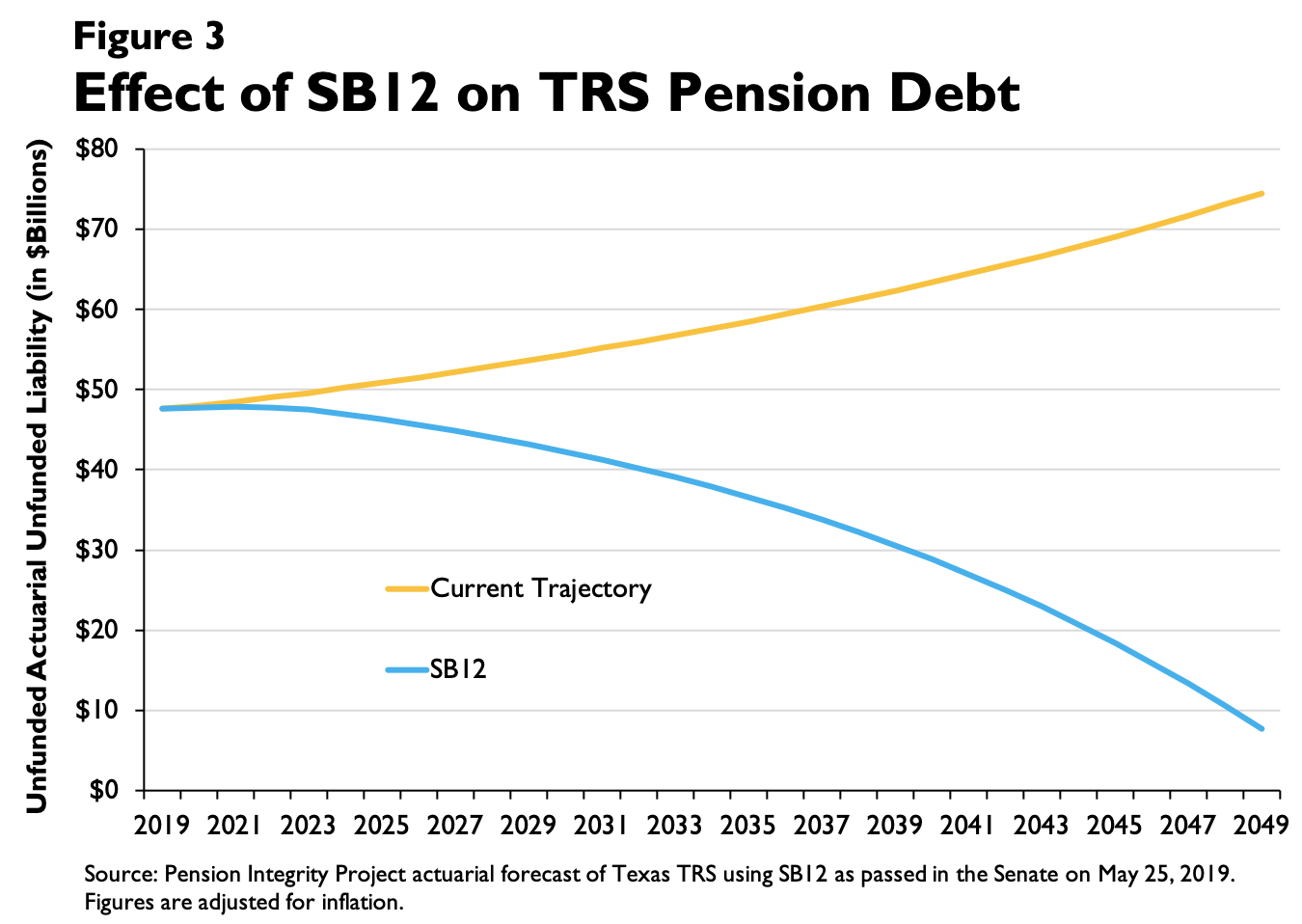

Figure 3 shows the forecast of TRS unfunded liabilities under the current contribution rates and the increases proposed in SB12. Assuming investment returns match the plan’s expectations—an important assumption, as we will discuss later—the additional contributions are projected to help transition the system from a path of ever-increasing pension debt to one of a gradual return to solvency.

The reform would have a similar effect on the funding ratio of TRS. Figure 4 demonstrates, if there’s no significant deviation from TRS assumptions, additional contributions would make a major difference in the system’s funding trajectory. As the contribution schedule is currently constituted, the funded ratio is projected to stagnate under 80 percent and eventually go down over time. SB12 is projected to alter this path so TRS would be close to reaching full funding in 30 years.

The trajectory towards full funding is of particular interest to active and retired TRS members, as it is directly connected to the state’s ability to provide COLAs and other benefit increases. According to Texas statute, the legislature cannot approve benefit increases for teachers —including COLAs—unless TRS is on the path to fully fund already promised benefits within 31 years. Without increased contributions, the prospect for a future COLA would be extremely bleak. However, with the new contribution structure outlined in the reform bill, TRS could possibly steer back into the statutorily required COLA funding period by 2023 — that is, if all actuarial assumptions are met, including investment expectations.

Overall, both the Senate and the House versions of SB12 are expected to achieve the minimum requirement for future COLAs—elimination of unfunded liabilities within 31 years—but whether that condition is sustainable may still be very sensitive to market factors.

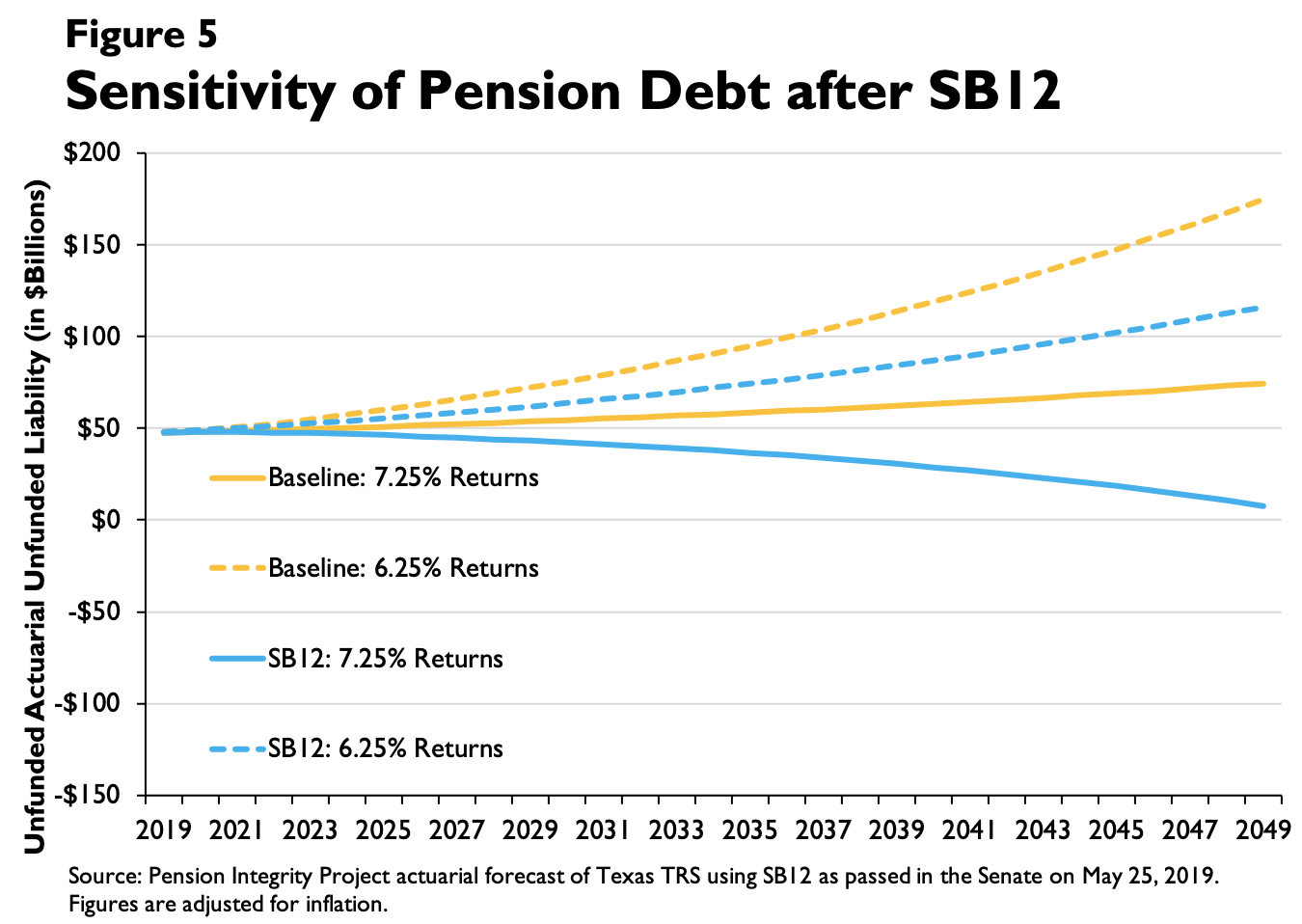

According to a recent analysis by the Pension Integrity Project, the largest contributing factor to the system’s $46 billion in pension debt was investment performance below the assumed rate of return. The recent reduction of this rate to 7.25 percent would help to reduce this factor going forward. However, the system’s future path still relies heavily on the accuracy of its return assumption.

Unfortunately, an analysis of TRS assets suggests that the plan is still very likely to experience long-term returns below the newly established rate. According to an Aon Hewitt report commissioned by TRS, the probability of achieving a 7.25 percent return over the long-term is just slightly above 50 percent.

Figure 5 depicts different possible outcomes for TRS unfunded liabilities over the next 30 years, calculated using actuarial modeling. SB12 is expected to lower TRS pension debts; however, projected unfunded liabilities can still vary greatly depending on the plan’s long-term experience with market returns. A long-term investment return of 6.25 percent—a return that Reason’s Pension Integrity Project believes to be a real possibility—will still be enough to prevent TRS from reducing its pension debts over time.

In other recent reform efforts that included increased contributions, policymakers have also simultaneously considered efforts to reduce the pension’s long-term exposure to market risk. In a 2018 set of meaningful reforms, Colorado not only increased the contributions in their public pensions but also established an automatic adjustment feature—automatically increasing annual contributions if certain funding thresholds are not met. Fort Worth soon followed suit enacting a similar automatic adjustment policy for its public workers’ pension plan.

Adding an automatic adjustment policy to increased contribution proposals not only improve the trajectory of TRS funding, but it would also insulate the system from unpredictable market returns in the future. Such a policy would allow annual contributions to freely adjust according to developing actuarial needs and ensure any future returns below expectations do not derail the system’s trajectory to full funding.

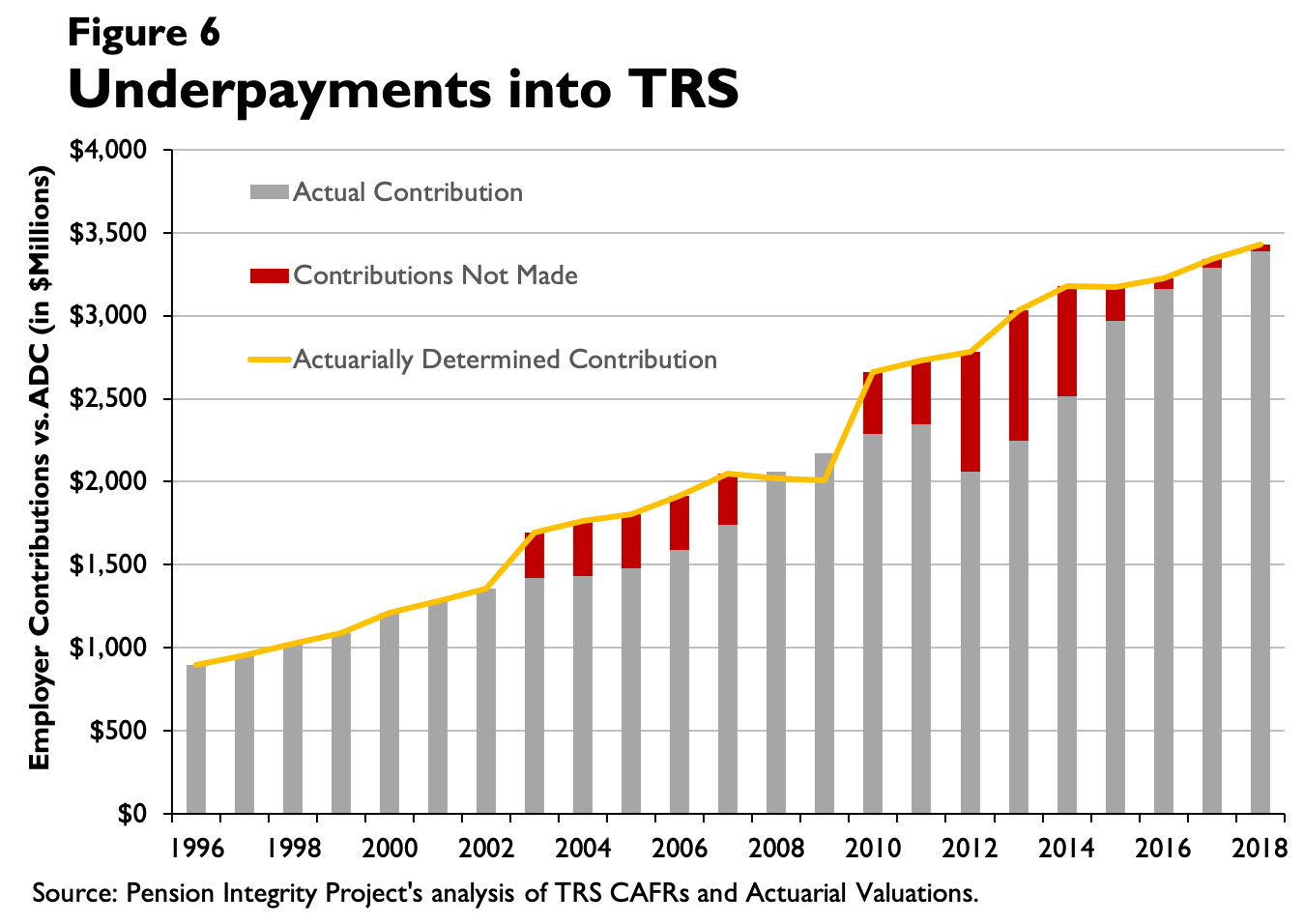

Another opportunity for Texas lawmakers to address the problem of contributions not adjusting to the variance in market experience would be for the legislature to contribute annually to TRS at an actuarially determined rate. Every year, TRS actuaries calculate the amount of total contributions from all sources needed to avoid any growth in unfunded pension liabilities. Yet today, the state relies not on this value to determine annual contributions, but rather on a fixed percentage of payroll set by law. The result of this policy is chronic underpayments into the TRS fund, which further adds to the system’s solvency woes. Figure 6 illustrates this problem, showing that state contributions into the fund have been below actuarially required amounts 14 of the last 16 years.

TRS would benefit from adjusting this policy to match many other states who rely on the actuarially determined amount to set annual contributions. This change in policy, like the proposed automatic adjustment feature, would protect the post-employment security of Texas teachers from the unpredictable future of the market.

Finally, the reform also misses out on the opportunity to address some of the weaknesses with the TRS plan design. The current structure of the TRS defined benefit pension plan tends to heavily favor teachers who stay in the system their entire career, leaving those who move on to other states or careers within the first five years—which is more than 40 percent of all newly hired Texas teachers—without the contributions made by the state on their behalf. Providing additional options with several different types of plans could better serve a larger range of teachers and accommodate a modern workforce that tends to value more flexibility and portability when considering retirement.

The Texas Legislature’s plan for getting TRS back to being actuarily sound represents a positive step toward securing the retirement of Texas teachers. The increases in contributions would provide a clearer path to solvency for TRS and a much needed 13th check to teachers. But, the reform’s success relies heavily on the fund’s ability to achieve expected returns over a long period of time. Because of this, the retirement security of 1.6 million Texas educators continues to be exposed to a great deal of risk. Although SB12 would provide much needed short-term relief to TRS members, additional reform would likely be necessary in the future.

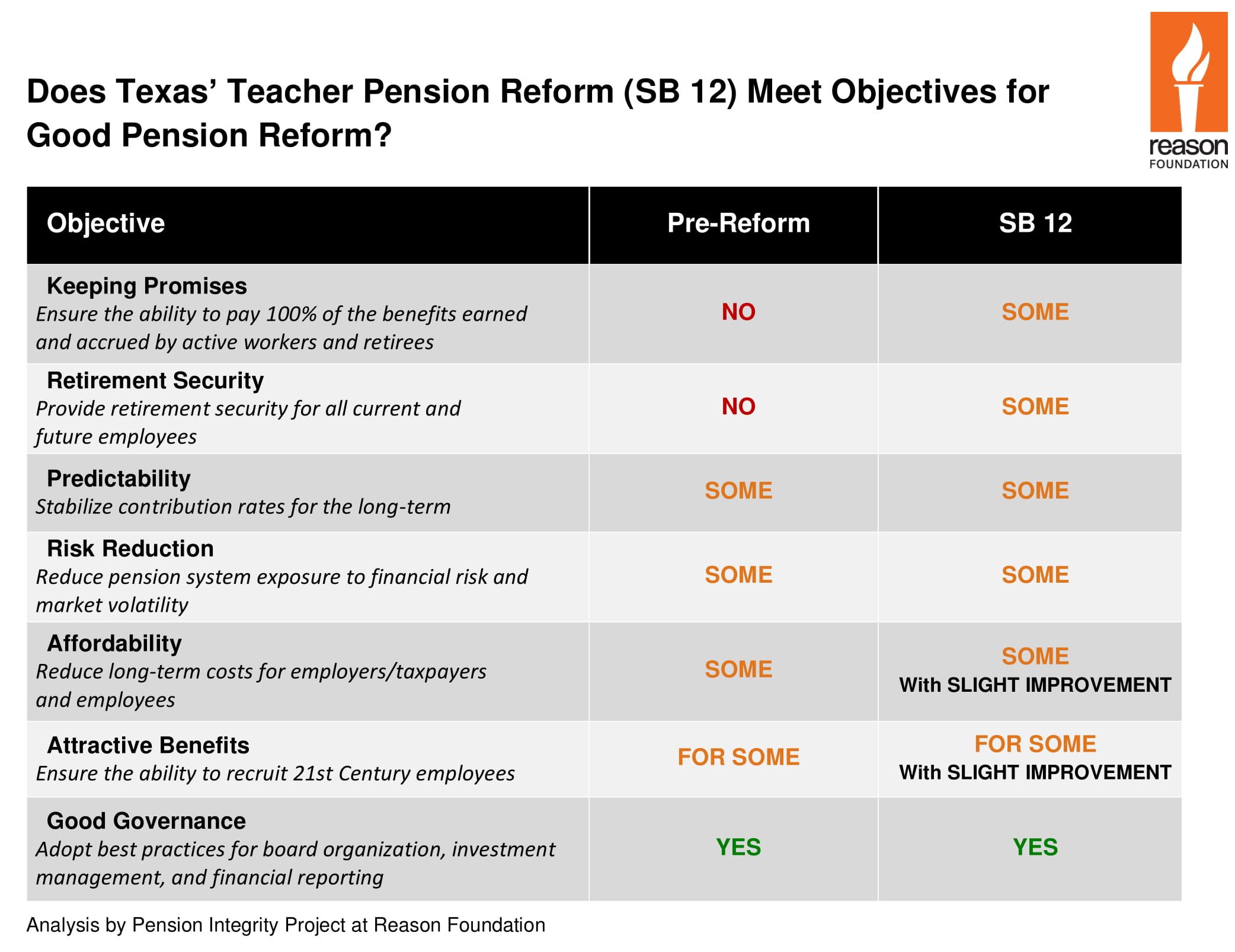

Below we present a breakdown of according to how well it meets the Pension Integrity Project’s reform objectives:

Does Texas’ Teacher Pension Reform (SB 12) Meet Objectives for Good Pension Reform?

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.