Colorado took a positive step towards improving the solvency of its public sector retirement system—the Colorado Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA)—through the recent passage of Senate Bill 18-200 (SB200), bipartisan legislation that changes pension contributions, cost-of-living adjustments, and the retirement age for future workers, all while expanding access to the optional PERAChoice defined contribution retirement plan to cover most state, local and higher education employees (but not teachers). Gov. Hickenlooper is expected to sign the legislation soon.

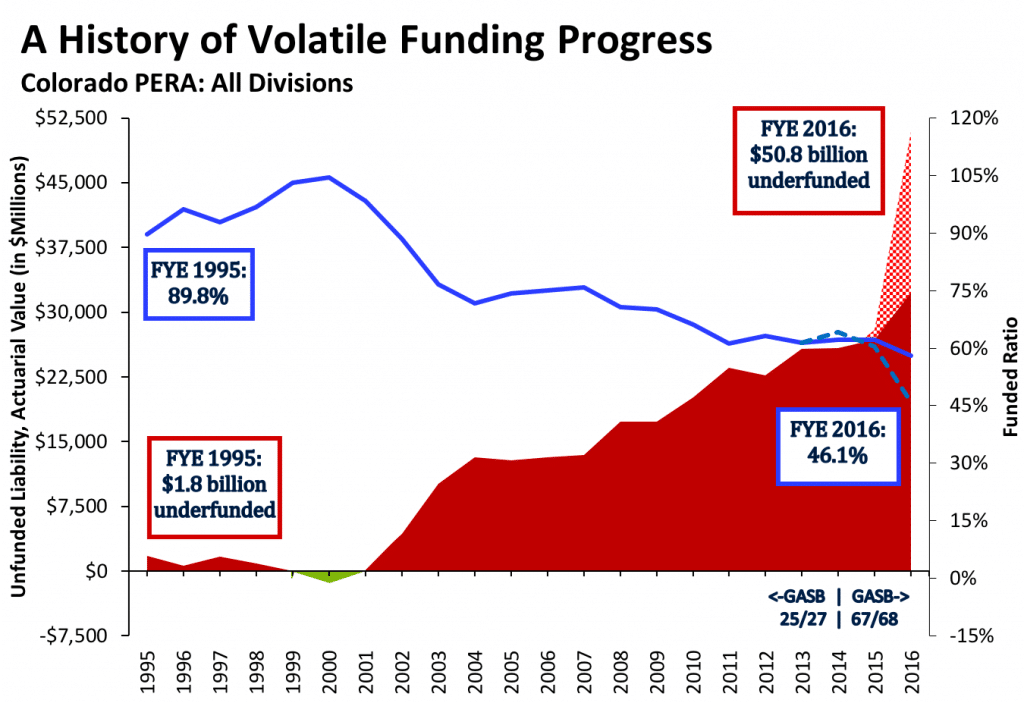

PERA currently faces an unfunded liability of around $51 billion, with a funded ratio of 46 percent (based on GASB accounting standards). Colorado and its school districts have been facing the threat of a credit rating downgrade. And projections by the pension plan’s actuary showed that, absent reform, there was a possibility the dollars set aside for teachers could run out in the 2040s.

SB200 aims to keep promised benefits protected primarily by increasing employer, employee, and state general fund contributions. The pension legislation also reduces COLAs for existing retirees by freezing the so-called Annual Increase for this year and next year, and lowering the cap on the annual Increase to 1.5 percent beginning fiscal year 2020. The retirement age for workers hired after January 1, 2020, is increased from 60 to 64 under this legislation, and those members must satisfy a Rule of 94 (combination of age plus service years) to get a full, unreduced pension benefit.

To address structural challenges with PERA, SB200 creates a new bicameral pension oversight committee, requires that employers make the same payments towards the unfunded liability whether or not their members participate in PERAChoice, and expands access to the PERAChoice option to local government workers (previously only certain state employees could choose a defined contribution plan). Further, SB 200 allows for automatic increases in future contributions rates and decreases in the Annual Increase if necessary to keep PERA on a path towards being fully funded over 30 years.

The bill does fall short in a few areas, however:

- It does not address the plan’s problems with overly optimistic assumptions, namely the assumed rate of return.

- The definition of success for the PERA board remains targeting a 30-year funding period, which is much longer than the time horizon should be for paying off unfunded liability according to current best practice standards established by the actuarial profession.

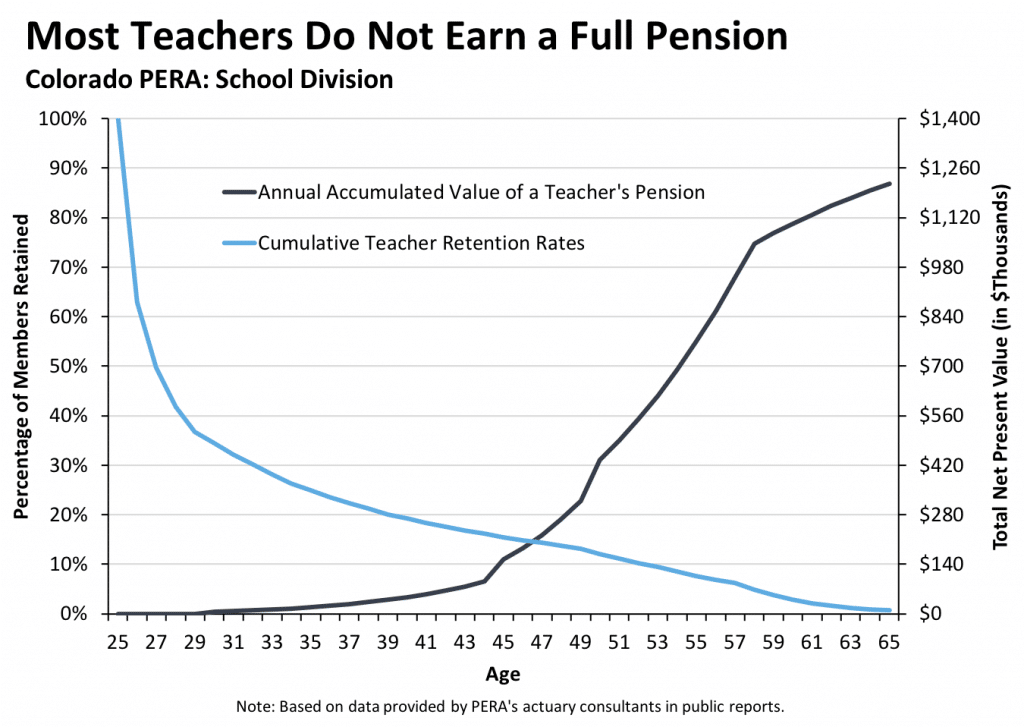

- The legislature missed an opportunity to reduce risk by expanding access to a choice of retirement plans to teachers — instead allowing only state and local employees to decide whether they want the more personal PERAChoice defined contribution retirement plan instead of the pension benefit. Opening the DC option to all workers would provide more flexibility to a wider variety of workers — less than 5 percent of teachers earn a full, unreduced pension benefit and many would be much better off with a DC plan — while simultaneously reducing the financial risks faced by PERA and state government.

Despite its shortfalls, SB200 remains a major step in the right direction. It institutes much-needed increases to contributions and adjusts the retirement age to better match a population that is living longer than before. Additionally, the formation of the new pension oversight committee leaves the door open for further incremental reform down the road.

The Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation worked with a wide range of PERA stakeholders over the past year, providing technical assistance to Colorado policymakers, education groups, business community groups, and a Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce pension reform working group as the reform discussions—and ultimately SB200—took shape. In addition, we conducted an extensive legislative outreach effort and provided advanced analysis and actuarial modeling to legislators as various options for reform were considered throughout the legislative process.

1. The Problem

PERA is an association of five separate defined benefit plans and an optional defined contribution plan, known as PERAChoice. The five pension plans are known as the State Division (covering employees at state agencies and in state-wide ‘hazardous duty’ roles), the Schools Division (covering all teachers and public school employees outside of Denver), the Denver Public Schools (DPS) Division, the Judicial Division, and the Local Division (covering most municipally employed workers who are not police or firefighters).

PERA was last fully funded in 2001. Like many other pension funds across the country, PERA has seen a consistent expansion in unfunded liabilities over the last fifteen years. By 2016—the latest reported year—the unfunded liability had grown to a stated $32 billion, with assets covering only 58 percent of the benefits promised to public workers. Given that that figure is based on PERA’s overly optimistic investment return assumption, the problem is likely more severe. According to PERA, the 2016 unfunded liability is actually $51 billion with a funded ratio of just 46 percent when calculated using methods prescribed by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB).

With its PERA pension liability growing faster than government revenues, Colorado has begun to feel the pressures in their budget, making it more difficult to allocate for other critical services. Chronic underpayment of required contributions—an artifact of a statutorily-mandated employer contribution rate that has proven much too low relative to actuarial funding standards—has resulted in a darkening outlook for Colorado’s credit rating. More importantly, the growing funding gap has become a major threat to the financial security of all workers and retirees under PERA, which accounts for around 10 percent of Colorado’s population.

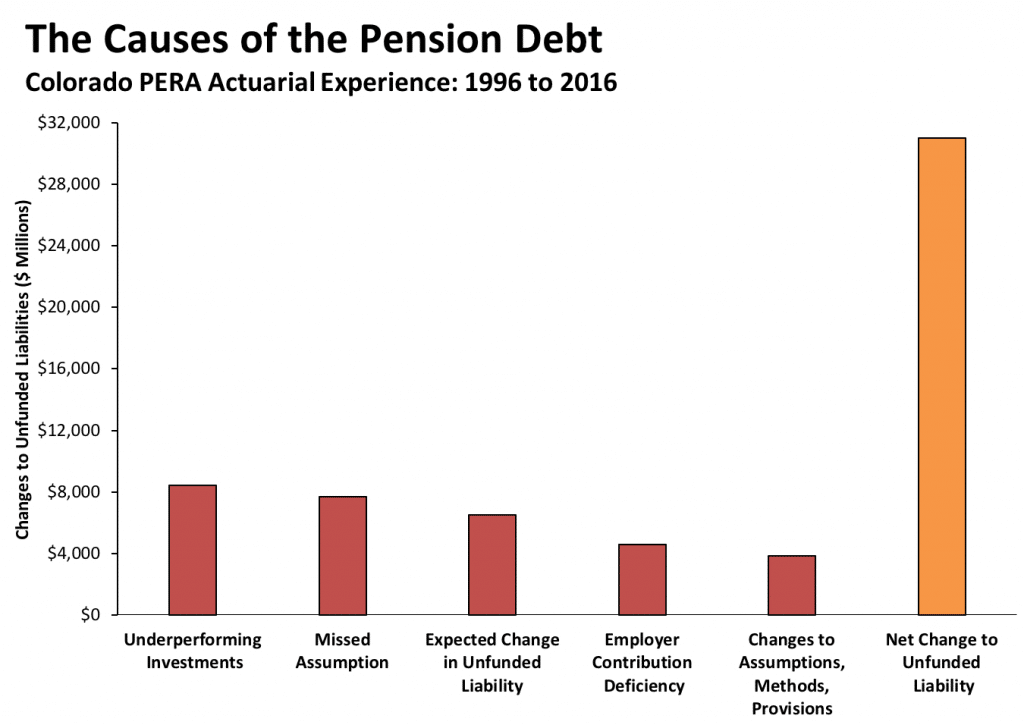

While some observers may assume that PERA’s current unfunded liability is primarily the result of underperforming market returns, the Pension Integrity Project’s analysis of PERA’s valuation reports—available in this interactive visualization—shows that the growing pension liability stems from several different factors.

As shown in the figure below, the largest contributor to the unfunded liability has been underperforming investments, which has added $8.4 billion since 1996. Over that period of time, PERA’s assets have consistently returned less than the assumed rates.

Other actuarial factors such as the withdrawal rate and the age at retirement have differed from assumptions, leading to another $7.7 billion added to the unfunded liability from 1996. These factors along with recognizing additional pension debt through assumption changes account for more than two-thirds of the final $32 billion in estimated unfunded benefits payments.

The other third of the unfunded liability is the result of Colorado’s underpayment of actuarially required contributions. Since 2003, Colorado has paid below the amount required to prevent a decrease in the funded ratio. Much of this is the result of Colorado establishing fixed contribution rates in statute, as opposed to using the actuarially determined contribution rate in any given year. This faulty approach is structurally underfunding the plan, which hasn’t been able to keep up with rapidly growing pension obligations. As a result, PERA has added $4.6 billion to the funding gap since 1996. Another $6.5 billion can be attributed to interest on the pension debt, meaning that the state is having to pay interest on the unfunded liabilities.

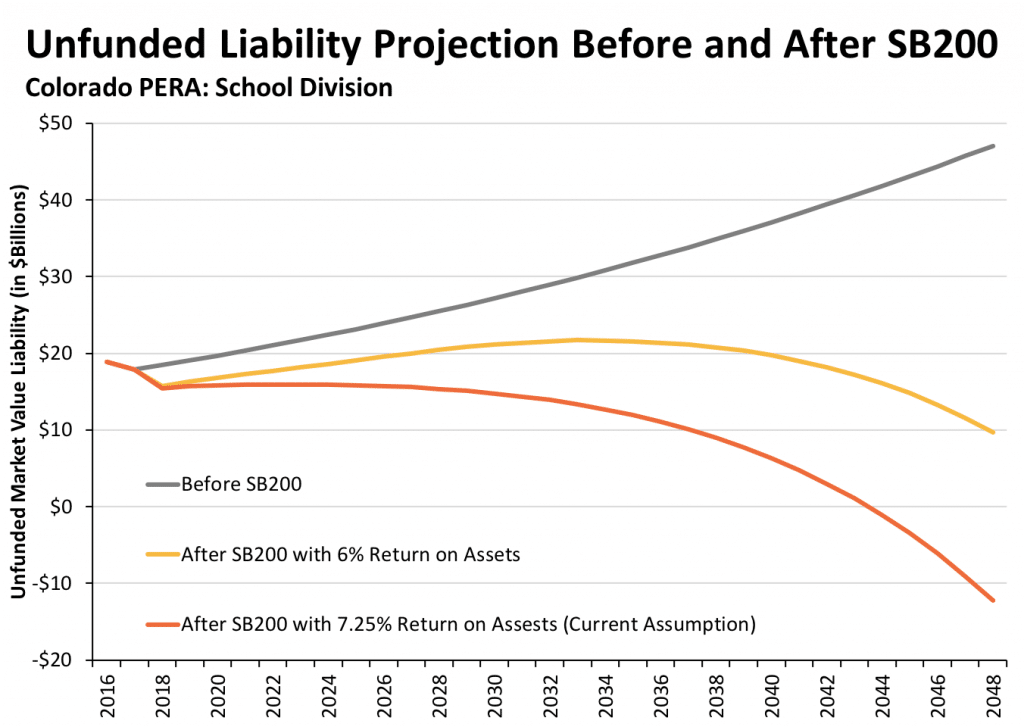

Using independent actuarial modeling, Reason’s forecast shows that without changes to PERA, the unfunded liability will nearly double over the next 30 years. And that assumes that actual returns will match current PERA assumptions, which recent history demonstrates is not a sure thing.

2. The Changes

Efforts to overhaul PERA began in 2017 after a stress test analysis (known as the “PERA Signal Light” study) showed it was possible that the State and School divisions could run out of money by the 2040s without a meaningful set of changes. The executive leadership at PERA went on a tour around the state to communicate to employees, retirees, and other stakeholders about the problems the system was facing. Around the same time, the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce formed a working group (including members of the legislature, the business community, and subject matter experts) to discuss what should be done. And concurrent with this activity was ongoing work by education community groups (primarily Secure Futures Colorado) to encourage rational, needed changes.

By March 2018, House Majority Leader K.C. Becker (D) and Sen. Jack Tate (R)—both members of the Chamber working group—agreed to jointly champion a bipartisan pension reform bill to be introduced starting in the Senate. Additional co-authors on the bill included Sen. Kevin Priola (R) and Rep. Dan Pabon (D).

The elements of SB200 as introduced were grounded in a set of recommended changes by the PERA board from late 2017 and supplemented with ideas developed by the Chamber of Commerce working group and best practice policies recently adopted in various state-level reform efforts.

The final version of SB200 as enacted was the result of two months of vigorous debate on the various aspects and components of the bill and included a number of compromise positions such that it could be collaboratively embraced by the Republican-controlled Senate (passed 24-11), Democrat-controlled House (passed 34-29), as well as the Governor’s office, employer groups, and PERA itself.

SB200, as adopted by the Colorado legislature in 2018, makes the following changes:

Contribution Changes

- Employees will contribute more of their pay towards PERA. Increases will begin in 2019 and will gradually ramp up to an increase of 2 percent of pay by 2021. The employee contribution rate will at that time total 10 percent for most PERA workers.

- All employers besides those in the Local Division will chip in an additional 0.25 percent of their payroll towards PERA, putting the contribution rates for the State, Schools, DPS, and Judicial Divisions at 10.4 percent.

- Future contributions will be based on gross compensation instead of net compensation (because benefits are based on gross compensation).

- It is noteworthy that no one has a clear sense of how much the shift from “net-to-gross” compensation as the basis for determining contributions will generate for PERA. Estimates range from a 1 percent increase in total contributions to a 5 percent increase — both relatively small amounts on an annual basis, but that could add up to a considerable amount in the long-run.

Benefit Design Changes

- Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs) — known as the Annual Increase — will be suspended for two years and reinstated in 2020 at a reduced rate. PERA members who are eligible for an Annual Increase will have that adjustment capped at 1.5 percent, down from the up to 2 percent increase before.

- New hires starting January 1, 2020, will have an increased retirement eligibility age, up to 64 from the previous age of 60 for state workers and 58 for teachers.

- New members will also have to satisfy a “Rule of 94” — the combination of age plus years of service should equal at least 94 — in order to receive unreduced benefits.

- The option to take part in the PERAChoice plan — a defined contribution retirement plan with 10.25 percent employer contributions and 10 percent required employee contributions — will be expanded to employees in the Local Division and to the non-professor staff at colleges and universities

- This option was previously only available to employees in the State Division (such as staff at state agencies, district attorneys, and members of the legislatures).

- Professors at colleges and universities already have access to DC plans if desired — managed separate from PERA — but non-teaching staff did not.

- PERAChoice will still be unavailable to the Denver Public Schools Division and the Schools Division, which together comprise the largest group of public employees in the state.

Structural Changes

- PERA will adopt an “Automatic Adjustment” feature for future contribution increases, should the above changes to contributions and the COLA not be enough to keep PERA on a trajectory towards being fully funded in 30 years.

- When total contributions are less than 98 percent of the total Actuarially Determined Contribution (ADC) the employee and employer contribution rates will increase (by up to 0.5 percent of pay a year) and COLAs will decrease incrementally (by no more than 0.25 percent a year).

- The maximum increase in the employer and employee rates is an additional 2 percent of payroll.

- The COLA can never drop below 0.5 percent.

- The funding policy for unfunded liabilities will be adjusted so that pension debt payments are paid on total payroll of PERA. This allows for expansion of the DC option without reducing crucial debt payments to the pension fund.

- The Legislature will establish a bicameral PERA oversight committee, which can request reports, propose legislation and make recommendations to PERA.

- The Legislature established an objectives statement for the optional DC plan that emphasized the role of PERAChoice as being a retirement plan intended to build retirement income for members.

- Many DC plans fall short of meeting this objective because they are only focused on general wealth accumulation in a supplementary capacity, and not designed to explicitly target the production of retirement income for the participant.

Grading the changes in SB200 according to the Pension Integrity Project’s seven objectives of good pension reform provides a useful evaluation of the enacted legislation. Judging the changes to PERA according to this grading method shows that the bill falls short in achieving a full remedy in some instances but manages to accomplish—at the very least—slight improvement in all of the seven objective categories.

Keeping Promises: The adopted legislation will improve the solvency of PERA through increased contributions with automatic adjustments and a reasonable adjustment to the supplementary Annual Increase. The increased retirement age for new hires establishes a more realistic and achievable promise and also improves the plan’s ability to reach solvency. All of these changes are made without cutting any earned pension benefits already made to members and retirees.

Without the adopted changes, PERA was forecast to have perpetual growth in unfunded liabilities, as shown in the figure below. With the adopted changes — particularly the automatic adjustment feature — there is a path to fully fund PERA as long as actuarial assumptions are reasonably accurate. If investment returns average less than 5 percent over the next few years and decades, the state will need to come back to the drawing board.

Retirement Security: Expanding PERAChoice to the local government division will mean a slight expansion of the availability of retirement security, but this option remains unavailable to the schools and DPS divisions. The PERAChoice Defined Contribution (DC) Retirement Plan has a generous employer match that provides a path to retirement income security. The back-loaded pension plan works best for full-career workers, and it remains available to all future hires.

Predictability: The current political practice in Colorado favors the near-term illusion of predictability in contribution rates by putting them in statute, while dealing with the need to increase contributions every few years because actuarial assumptions used by the plan have not matched positively with actual experience. This was not changed with SB200, meaning the annual contributions will continue to be slow to adjust, which was a major source of growth in the unfunded liability over the past two decades.

One small improvement in favor of long-term predictability was the expansion of access to the PERAChoice DC Retirement Plan, whose contribution rates are wholly predictable, to the local government division. However, continuing to use fixed contribution rates in statute that are dependent on an unrealistic 7.25 percent assumed rate of return means that long-term rates are not as predictable as if more conservative assumptions were used for the new tier of pension benefits (which would avoid repeating the primary cause of today’s problems).

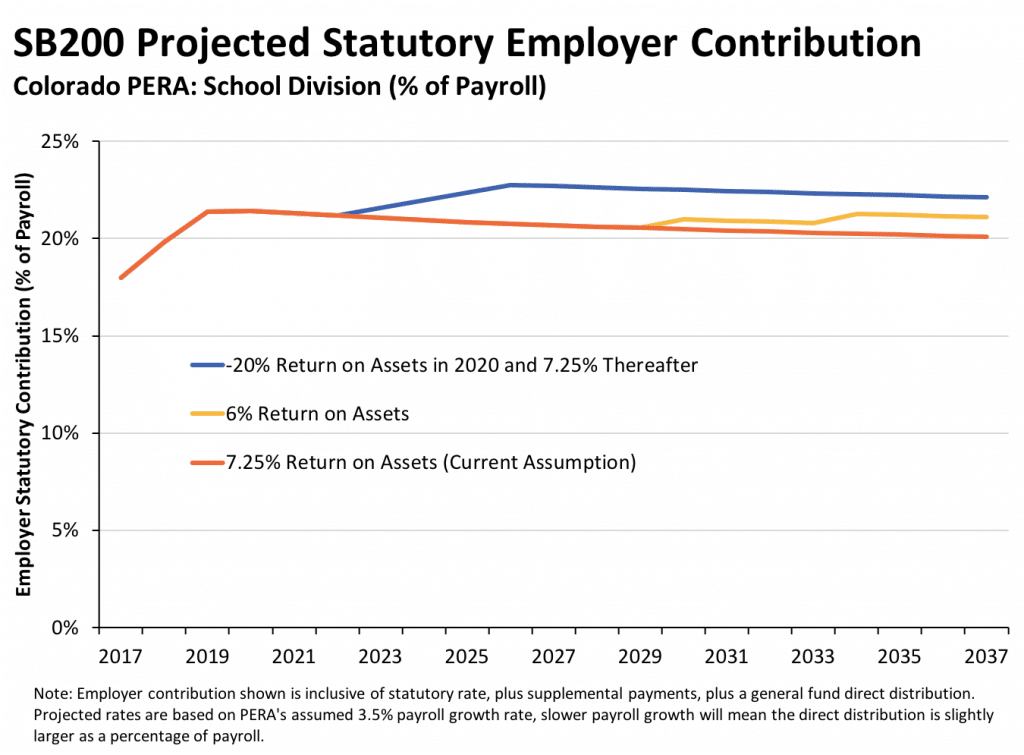

The chart below shows that it is still reasonable to expect a range of possibilities for contribution rates. A lot depends on the timing of investment returns when the assumed return itself has only around a 50 percent probability of being right. Actual volatility could look more wild than this analysis using the same average return for each year.

It is worth emphasizing that in a scenario where investment returns average 6 percent, reductions in the Annual Increase to as low as 0.5 percent in cost-of-living adjustments will be required to maintain the contribution rate trajectory shown. Year-to-year changes in contribution rates will depend on how exactly the PERA board decides to put the automatic adjustments into practice.

Risk Reduction: The pension plan will continue to be exposed to market volatility with PERA’s 7.25 percent assumed rate of return, which has only about a 50 percent probability of success. The expansion of PERAChoice provides a slight reduction in risk, as it will reduce PERA’s overall exposure to market risk and volatility.

Affordability: SB 200 will have enough additional contributions to ensure there is a path to pay down the unfunded liability in a reasonable time only if experience meets PERA’s actuarial assumptions. A lower return rate will prevent this plan from reducing the total amount paid into PERA in the long-run, and interest costs will continue to be a problem. The automatic adjustments help mitigate this risk, but the limits on the adjustments could render them insufficient within a few years — even if investment performance is strong over the long run.

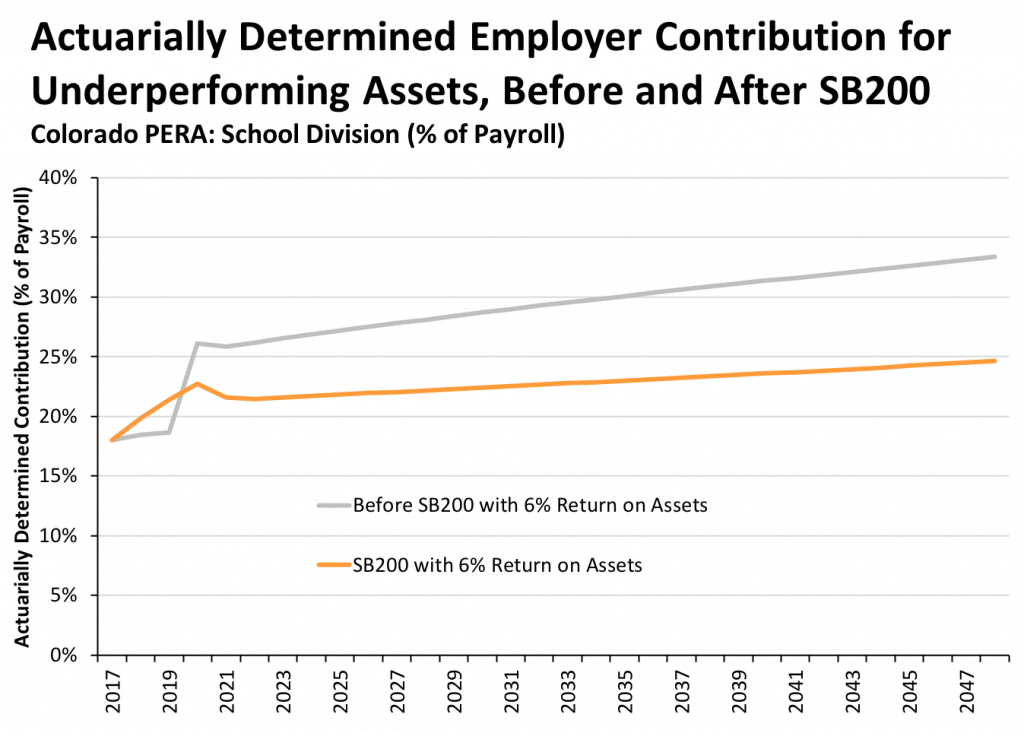

For example, when we look at the forecast for the actuarially determined contribution rate in the chart below, it is clear that the long-term trajectory is growth in required employer dollars, even after SB200. To be clear, a huge improvement from SB200 is that the total contributions for an underperforming market scenario will be less than if the status quo had been preserved. But SB200 still leaves PERA exposed to risk and the potential for an expensive future.

Attractive Benefits: Expansion of the PERAChoice DC Retirement Plan option gives the local division access to a competitive and attractive retirement plan for 21st Century employees, but this option still isn’t available to teachers in the schools and DPS divisions (Colorado’s largest category of workers).

Good Governance: The bill establishes a new Public Pension Legislative Oversight Committee to create a more robust framework for legislative oversight of PERA. The committee will ensure greater transparency, accountability, and the long-term sustainability of a secure and affordable retirement system.

4. Conclusion & Next Steps

SB200 made positive steps in most of the categories of good pension reform, but several key areas saw only slight or incremental improvements. In some ways, the bill falls into similar traps that eventually made the 2010 law known as SB1 a failure in retrospect.

The adopted bill doesn’t do enough to reduce risk. As is evidenced by the previous twenty years and projections going forward, PERA has a problem with investment returns not meeting the assumed rate of return. Previous reductions in the assumed rate have curtailed the risk for the fund, but our analysis shows that even more reductions are necessary.

Without a major change to the current assumption policy, PERA is likely to still have unexpected growth in liabilities resulting in yet another pension quagmire in the future. In the following years, Colorado policymakers (including the new Pension Oversight Committee) ought to consider a reform that reduces the assumed rate of return for the entire plan or for just the incoming hires of the newly established DB plan.

The expansion of the DC option does help with reducing risk, but this round of reforms still fell short of expanding this choice to the largest group of public employers in Colorado—teachers. By restricting access to the program, PERA is missing on an opportunity to reduce future risk in a way that is mutually beneficial to both the employer and the employee.

By limiting the expansion of PERAChoice from teachers, the reform also limits PERA’s ability to fulfill the important objective of providing attractive benefits. The defined benefit plan is an excellent option for many Colorado workers but lacks the flexibility and portability that some workers—i.e. the more than half employees who do not plan on staying for the rest of their career—may value. Future reform efforts in Colorado should prioritize making this program available to teachers as it is already for the rest of the state’s public workers. Expanding the DC plan is, after all, a positive step in two ways. It provides an additional option to those who would like to choose a DC and it reduces the risk carried by the government and its taxpayers.

In SB200, the Colorado Legislature has enacted meaningful improvements to the state’s pension system, which will lead PERA to a considerably improved long-term position. By improving policies in a way that is focused on keeping promises, retirement security, affordability, and good governance, policymakers of the Centennial State have greatly improved the post-employment security of their workers as well as the fiscal security of the state. Slight improvements in the objectives of predictability, risk reduction, and attractive benefits suffer from some unfortunately missed opportunities, but will also improve the overall security of the plan for all stakeholders. After a grueling legislative process filled with difficult decisions, Colorado lawmakers deserve credit for adopting effective, bipartisan pension reform.

Does Colorado’s 2018 Legislation Meet Objectives for Good Pension Reform? A Final Grade

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.