Last month, the 10-year Treasury yield rate hit an all-time daily low of 0.52 percent. The rate, which is often an indicator for other interest rates, has serious implications for public pension fund investment returns. As Pensions & Investments notes, “Public pension plans can expect to feel the squeeze, as lower [Treasury] rates will drive up their liabilities.”

Why the squeeze? Government and corporate bonds currently make up about 23 percent of US public pension investment portfolios and when the yield on these fixed income securities drops, so do the returns on these assets. This puts pressure on pension fund managers to find yields elsewhere in order to meet their set investment assumptions.

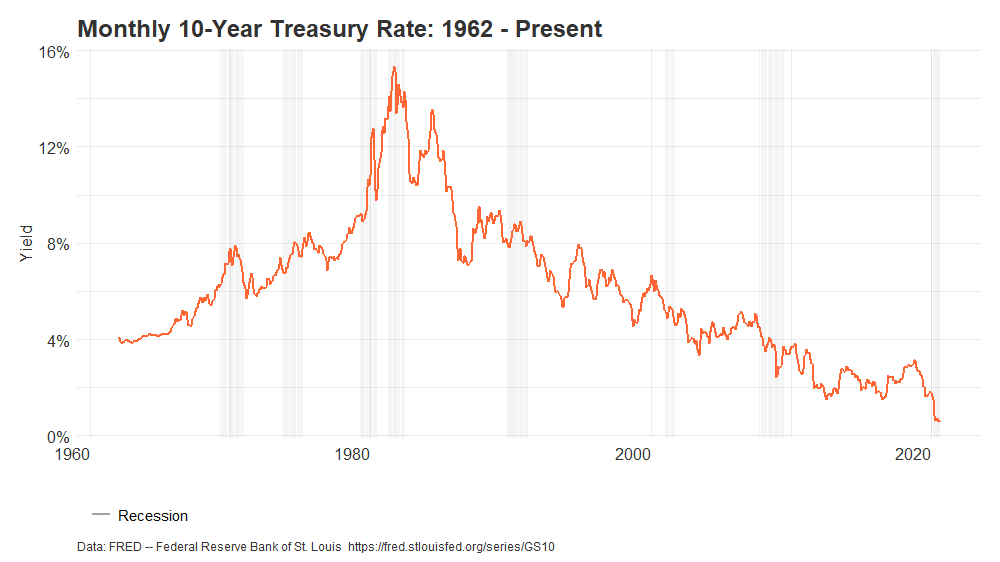

Low interest rates have hampered public pension asset returns for the last two decades. Coming off of the highs of the 1980s, the 1990s still saw decent yields with a decade average just below 6.7 percent on the 10-year note. Throughout the 2000s interest rates dropped, with an average yield of 4.46 percent. Since 2010, the rate has averaged only 2.32 percent. The lowest monthly yield was July 2020, with an average of 0.62 percent. The animated chart below displays this decline in 10-year Treasury yields.

New forms of monetary policy like quantitative easing and interest on reserves have depressed both long- and short-term rates. Unfortunately for public pension systems, these policies are unlikely to be unwound for several years, if not decades.

Seeking yield, public pension systems have shifted away from bonds (like Treasuries) and towards riskier portfolios that include more real estate, private equity, and alternative investments.

In 2001, fixed income made up 31.5 percent of US public pension system investments, but by 2019 that percentage had fallen to 22.9 percent, reflecting the rising levels of pension system risk-taking.

The all-time low on the 10-year note is the latest reminder of the new normal in institutional investing—an environment characterized by low interest rates, low economic growth, and eventually low equity returns. As the graph below shows, the new normal is a stark deviation from the 1980s and 90s.

Unfortunately, as the growing public pension debt shows, pension plans have been slow to adjust their investment return rate assumptions to this reality. Moving forward, outdated and artificially high assumptions on investment returns will likely continue to cause unfunded liabilities to soar and could put pressure on public pension plans to consider pursuing even riskier strategies in search of higher yields as they attempt to fund the retirement benefits they’ve promised to workers.