Why did the West Virginia Teachers Retirement System have a dramatic funding ratio improvement after switching back from a defined contribution to a defined benefit plan in 2006?

Such is the question frequently posed by interested parties across the country in their skepticism of public pension reform initiatives. Some claim that the switch back to a pension structure was the key ingredient to improving the teachers’ retirement plan, but an examination of this system’s funding history shows that what progress has been made can be mainly attributed to a shift and continuation in how the state paid for promised pension benefits.

The Funding Ratio Puzzle

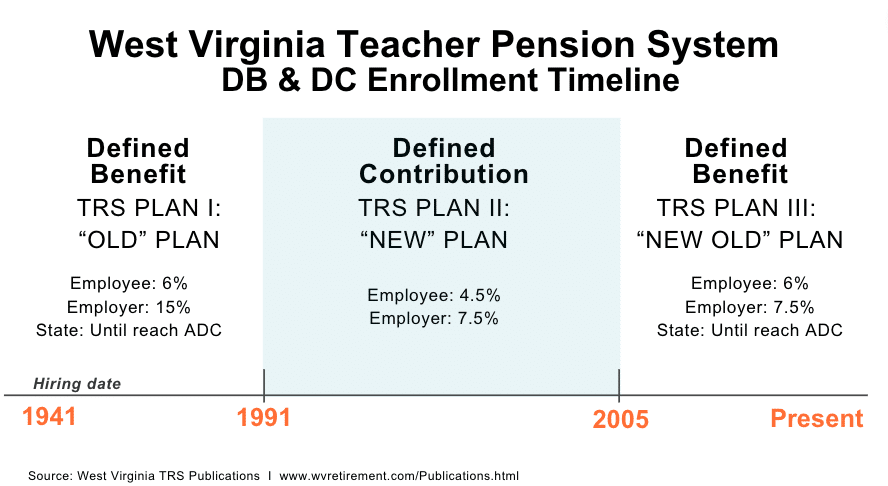

In 1991, bearing a single-digit funded ratio from its "pay-as-you-go" practice through the 1980s, the West Virginia Legislature voted to close new enrollments into the state's defined benefit (DB) pension plan for teachers. From then on, new hires were entered into the Teachers Defined Contribution Retirement System, TDCRS, a plan that gave a flexible individual account to each teacher, eliminating the risk of new members adding unfunded liabilities to the state.

A few years after the closure of new enrollments, funding of the teacher's DB pension had only slightly progressed, reaching a mere 11.6% by 1994. By 2006, the state made some additional progress, with the plan reporting a 32% funding level. This wasn't nearly enough. Frustrated with the continued low funding levels and pressured by state interest groups, the Legislature approved reopening the DB plan.

In 2016, merely a decade after reopening access to the pension, the defined benefit plan reached a 61% funding level. Currently, the Teacher Retirement System's DB plan has reached 78.4% funding, even surpassing the national average of 75.2% public pension funded ratio.

While it might appear from the timeline that the reopening of the defined benefit plan for teachers caused the funding ratio improvement, a closer inspection reveals a different story. To be blunt, West Virginia simply started dedicating enough money to pay for the pension promises it was making.

From DB to DC–and Back

To prevent an increase in unfunded liabilities the defined benefit plan was generating, new teachers hired beginning in 1991 were enrolled in a defined contribution (DC) plan. Members had a choice of allocating their contributions into 10 separate investment options, including government securities and common stock mutual funds, guaranteed insurance funds, individually allocated annuities, or lifestyle funds. The plan was funded through a combination of employee and employer contributions, with plan members contributing 4.5% of pay and their respective employers adding 7.5% to the fund. With a defined contribution design, the plan was to be, by definition, fully funded since inception—in perpetuity.

Enrollment in the defined contribution plan was interrupted in 2005 in response to pressure from employee unions to reopen the defined benefit plan. Newly hired teachers were enrolled in the DB track from there on, and current members in the DC plan were given the opportunity to switch to the new DB plan. More than 78% of the participants in the DC teachers plan (TDCRS) elected to transfer to the defined benefit TRS in 2008. As of 2022, the TDCRS plan has 3,026 members, while the defined benefit TRS plans (tiers I and III, pre and post-reform) have 71,968.

The State Supreme Court Ruling

In March 1989, in the first months of his first term, then-Gov. Gaston Caperton signed an executive order creating the Governor's Task Force to study public pensions. The task force revealed that due to the years of underfunding, the state faced $3.25 billion in unfunded liabilities. Subsequently, the state legislature swiftly moved to address what the West Virginia Supreme Court would later call the "hemorrhaging of the Teacher's Retirement System."

With the 1989 report in their hands, the West Virginia Education Association sued the state, alleging that the TRS pension system was run in an actuarially unsound manner, with unfunded liabilities representing a breach of contractual obligations.

The representatives of the plan members alleged that between 1985 and 1988, then-Gov. Arch A. Moore's administration did not deposit appropriate contributions to the teacher's fund, resulting in TRS having to withdraw from its reserve trust to cover the missing inflow. The net effect of the funding deficiencies was that by July 1994, the Teachers Retirement System had accumulated significant new unfunded liabilities.

The case was fought all the way to the state's Supreme Court, which set a precedent that drastically altered the pension and fiscal landscape of West Virginia. The court determined in the case Kayetta Meadows, et al. v. The Consolidated Retirement Board:

“The inadequate funding of the Teachers Retirement System is invalid since it violates the prohibition against impairment of contractual rights contained in the federal constitution” U.S. Const. art. I, § 10, cl. 1, and in the state constitution, W. Va. Const. art. III, § 4.”

The state Supreme Court did not rule on the underfunding of the plan itself, passing on the question of constitutionality by citing a recently passed State Senate bill intended to eliminate the unfunded liability for the teacher's plan. But the court mandated the full payment of the unfunded liability within 40 years of the decision—that is, by 2034.

The aforementioned funding bill was Gov. Gaston's 1994 Senate Bill 1000, mandating the legislature to set aside enough funds to cover any and all missing contributions from the counties and municipalities to meet actuarially determined contributions. Recognizing the bill but still aiming to ensure the retirement benefits of plan members, the court established that if the state legislature fails to do so, the acting governor would be liable for allocating the funds needed to pay for promised pension benefits.

As described in every West Virginia annual financial report since the ruling:

“The State Supreme Court has required the State to fund the Teachers’ Retirement System in an actuarially sound manner to eliminate the unfunded liability over a forty-year period beginning on July 1, 1994, and to meet the cash flow requirements of the TRS in fulfilling its future anticipated obligations to its members,”

This is why, since the 1995 court ruling, West Virginia has been contributing to their teacher's plan fully up to—and often beyond—the yearly actuarially determined contribution.

The Increase in Contributions

The improvement in the funding ratio of West Virginia's teacher pension fund in the past decade is notable. The plan went from 11.6% funded in 1994 to 78.4% in 2022. As the West Virginia Supreme Court ruling above should make clear, however, the reason has nothing to do with reopening the defined benefit plan.

Because of the Supreme Court ruling and SB 1000, the state legislature has been subsidizing the fund, providing TRS the funds needed to meet and surpass the required actuarially determined contributions (ADC) to fully fund the plan by 2034.

Funding for the teachers' DC and DB plans is set as a fixed percentage of payroll from employees and employers, which are established by state law and not actuarially determined in West Virginia.

Following the ruling mandating the extinguishing of the TRS unfunded liabilities by 2034, West Virginia appropriates state budgetary funds and a percentage of fire insurance tax revenue to supplement employee and employer contributions. Since then, the TRS DB plan has been consistently receiving the appropriate– and often beyond– funds to become solvent by the 2034 deadline.

In fact, the West Virginia Legislature has contributed much more to the teachers' retirement fund than the teachers or school districts combined. The latest actuary report reveals that 22% of contributions came from employers, 16.5% from employees, and 61% from the state—with the legislature most recently contributing $355 million in 2022.

The state also dedicated extra funds to accelerate the eventual full funding of the Teacher Retirement System. The substantial spike in contributions in 2006 and 2007 is from an $800 million tobacco general obligation bond issued by the state to increase funding into the plan. Due to this supplemental infusion of revenue, the funding ratio jumped from 24% to 51% in three years, significantly accelerating the recovery of the plan's funding ratio.

Why Not During the Defined Contribution Regime

But, if the Supreme Court mandated in 1994 that the legislature supplement contributions to the plan, then why didn't the ratio improve as much while new members were being enrolled in the defined contribution plan from the years 1991 to 2005?

It did, but only slightly. The impact of increased funding to the DB takes a few years to recognize its full effect, but funding ratio improvements have been seen since the state contributions started to trickle in—with the funding ratio doubling between 1995 and 2005, from 11.4% to 24.6%.

It is important to note the funding ratio discourse pertains only to the defined benefit plan. All funding figures refer to the funding of the teachers' defined benefit plan only. By definition, the DC plan was, since its inception, and still is, entirely solvent. The plan's benefits are the outcome of the contributions put in, compounded through the years of service. Teachers hired after 1991 were enrolled in a fully solvent plan that did not expose state budgets to unexpected growth in liabilities and costs.

As a Bellwether Education Partners report theorized, "Perhaps lawmakers in West Virginia fell prey to the idea that by switching from a pension to a DC, the legacy cost of the pension would, much like new enrollees in the fund, simply go away."

In reality, a change in plan design—like the one West Virginia took on in 1995—only impacts the future growth of liabilities, and it takes decades to realize the real impact of this type of reform.

West Virginia's switch to a defined contribution plan was never meant to be a comprehensive solution to completely eliminate the unfunded liabilities of the teachers' plan. It was merely a strategy to avoid runaway costs in the future. The massive accrual of unfunded liabilities existed before and after the 1995 reform, and the state's long path to funding promised benefits doesn't really correlate to the type of plan new teachers are going into.

Lessons?

This case will continue to capture the attention of stakeholders beyond West Virginia, searching for lessons in the funding trajectory success that can be replicated in other states. For such purposes, it is essential not to let vested interests obscure the truth.

The remarkable recovery of West Virginia's Teacher Retirement System's defined benefit plan reveals a complex narrative that transcends simplistic observations of the defined benefit reopening timeline. The West Virginia funding journey is not one of a victory of defined benefit or failure of defined contribution structure.

Central to this story is the fact that the catalyst for the TRS plan's journey to financial health was not the switch back from DC to DB, but rather a pivotal court mandate that ensured the funding of actuarially determined contributions by the state legislature. Often overlooked in cursory analyses, this independent intervention leading to appropriate funding of the plan is the true steering force behind the plan's remarkable funding improvement—not the benefit structure switch.