Rent control is a central focus of discussion in the ongoing national debate about housing affordability. While big rent control initiatives like Proposition 33 in California and commercial rent control previously proposed by the outgoing Biden administration seem to be out of the picture for now, municipalities in Maine (Old Orchard Beach) and California (Santa Ana) have approved rent control measures, and a measure to deregulate a similar policy in Hoboken, N.J., failed during the November election.

As a producer and director of Shabbification: The Story of Rent Control, I wanted to explore how these policies, intended to protect tenants, often lead to unforeseen and damaging outcomes for cities like New York. The idea for Shabbification came from witnessing the growing challenges faced by small property owners and tenants alike in New York City and New York State. Through this film, I wanted to capture the personal stories that statistics often fail to convey—stories of landlords trying to keep their buildings from falling apart and tenants navigating a system that no longer serves them.

At its core, rent control—and its other forms, like rent stabilization—is a form of government-enforced price limits on rental properties. These policies set caps on how much landlords can charge their tenants, aiming to make housing more affordable. Yet, New York City, the epicenter of long-standing rent control policies, is a cautionary tale of what happens when such regulations are allowed to linger for decades.

Since the late 1960s and early 1970s, New York has implemented and expanded rent stabilization programs. These programs have been recently bolstered with the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act of 2019 (HSTPA) and the Good Cause Eviction Law of 2024. Today, about one million apartments in the city fall under these laws. Initially conceived to address housing shortages after World War II, rent control has worsened the very crisis it was meant to alleviate.

My documentary shows the harsh realities of rent control, offering viewers an intimate look into the lives of small property owners who bear the brunt of these regulations. Small landlords, many of whom own just one or two buildings, struggle to maintain their properties under the crushing weight of government-imposed rent caps. What was meant to increase housing access by keeping rents low has stifled development and reduced the availability of livable units when landlords no longer earn enough money from rent to maintain them.

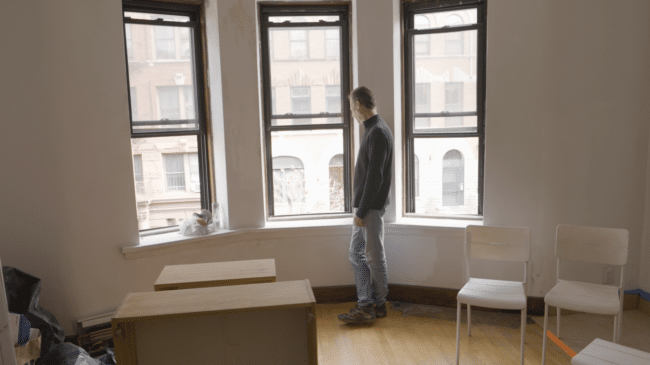

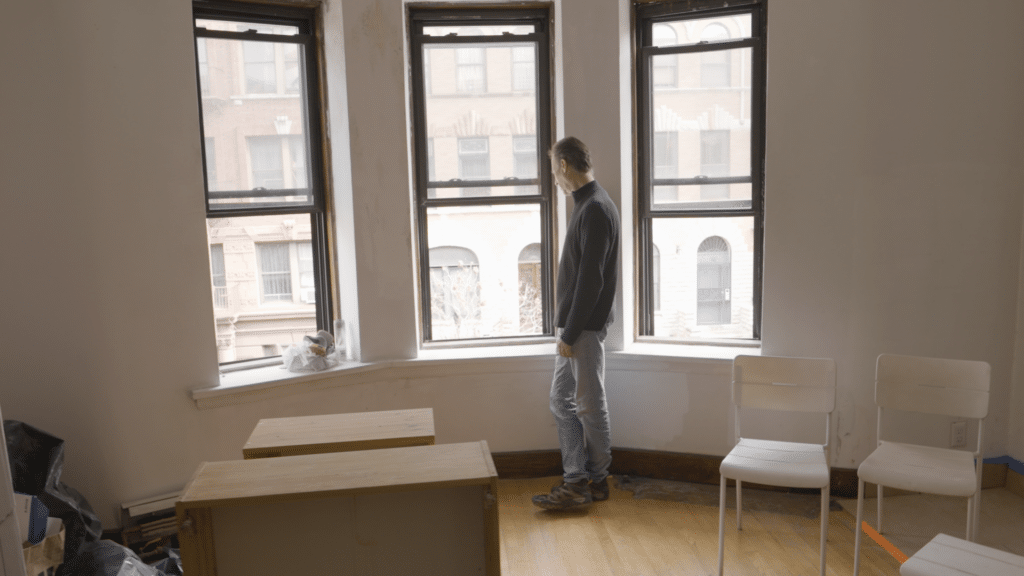

The documentary brings us into the deteriorating apartments of New York, revealing how these outdated policies have led to crumbling infrastructure, deferred maintenance, and vacant units. In the opening scene, Eric Dillenberger, a board member of the Small Property Owners of New York, walks through an Upper West Side building where a tenant lived from 1969 until 2021. The unit is currently vacant. He explained that, with current rent control regulations, it would take him 180 years to recoup the investment needed for renovations. This is because the unit requires extensive renovations—estimated to cost $200,000—just to make it livable again. Under the HSTPA, rent increases for Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs) are capped at a mere $89 monthly. The law further limits the amount of reimbursable IAI spending to $15,000 every 15 years for up to three improvements—the reason why it will take just under 200 years to make up for the renovation. The math is staggering and underscores just how unsustainable the system has become for small landlords.

The story of Bryan Liff, a small property owner in Harlem, offers a striking example of how rent control policies can disrupt both tenants and landlords. Bryan bought his building—a set of studio apartments—just a few months before the HSTPA took effect, intending to renovate, modernize, and make the property environmentally sustainable. At the time of purchase, the building was largely vacant except for one rent-stabilized unit.

After HSTPA, Bryan was no longer allowed to charge market rates for the other vacant units, making his renovation plans financially unfeasible. Additionally, under New York rent stabilization laws, Bryan cannot claim more than one unit for himself and his family, even though the building remains mostly empty. This leaves Bryan unable to move his family into the building or make the necessary structural improvements, as the capped rental income would not cover the costs.

Bryan’s story reflects a larger crisis playing out across New York City, where small landlords face mounting financial hardship. Policies that were intended to protect tenants have inadvertently prevented landlords from maintaining or utilizing their own properties, contributing to the very housing shortage these laws were meant to solve.

This leads to broader implications for the city itself. New York is facing a historic housing shortage, with vacancy rates plummeting to just 1.4%—the lowest in decades. Despite the desperate need for housing, tens of thousands of rent-stabilized apartments remain off the market, left vacant by landlords who cannot afford the upkeep or face regulatory barriers. Rent control, initially designed to protect tenants, has inadvertently locked thousands out of the housing market. Instead of incentivizing property owners to provide more housing, the policy disincentivizes repairs and upgrades, pushing landlords to leave units empty or underutilized.

The situation has become so dire that an estimated 20,000-60,000 rent-stabilized apartments remain vacant during a time when demand for affordable housing is at an all-time high. This paradox of widespread housing shortages coupled with vast numbers of empty apartments is a direct consequence of rent control’s distortion of the housing market.

So, what can policymakers do? There are smarter solutions that could alleviate the housing crisis without exacerbating the problem with rent control. Housing vouchers, for instance, could provide targeted subsidies to low-income tenants, allowing them to access housing in the private market without the need for price caps. This approach would offer tenants immediate relief while giving landlords the flexibility to maintain their properties and invest in their communities. Additionally, easing restrictive zoning and building regulations would encourage new development, expanding the housing supply and driving down rents.

A small property owner from Chinatown (who chose to remain anonymous), whose family purchased a building in the 1980s, reflects on the absurdity of the current system: “Here you have existing housing stock that could be easily made available if the laws changed and allowed property owners to get the necessary income. This is a basic common-sense proposition to addressing the housing crisis in New York City.”

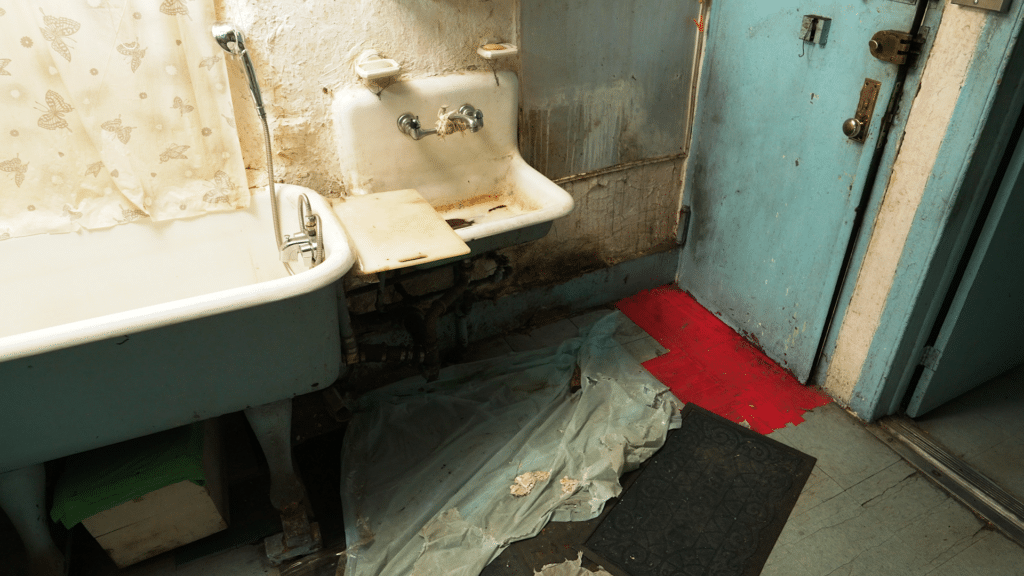

The unit that he walked us through has not been renovated since the 1910s. For decades, a long-term tenant occupied the property, and now, with the unit vacant, the owner faces a familiar dilemma: Under current rent stabilization laws, the restrictions on rent increases make it economically impossible to justify the significant costs of renovation. The unit remains stuck in a state of disrepair, unable to be brought back into the housing market despite a desperate need for available units.

This case highlights a broader issue across the city: rent control policies, while intended to protect tenants, have left thousands of units unlivable and empty. While these laws remain in place, small landlords remain unable to modernize aging buildings, worsening New York’s housing crisis.

Through this documentary, I wanted to provide a window into the reality of rent control, showing not only its failings but also the people who are most affected by it. It reveals that, far from being a simple fix, rent control is a deeply flawed policy that needs serious reconsideration if we are to solve the housing crisis and create a more just and functional system for both tenants and landlords.

It’s a common concern that removing rent control or stabilization policies would cause rents to skyrocket, but the opposite is more likely to occur in the long run. By releasing thousands of vacant, rent-stabilized units back into the market and incentivizing landlords to maintain and upgrade their properties, the overall housing supply would increase. This expanded supply would provide more options for tenants, easing competition and driving prices down. A healthier, less restrictive housing market would ultimately benefit tenants by improving availability, affordability, and quality—without the distortions and scarcity created by rent regulations.