In a recent meeting, the Arkansas state pension board of trustees touched on growing concerns revolving around pension underfunding. But they fell short of constructively discussing solutions.

The numbers show that there is good reason for concern. In 2018, the pension plan covering state employees had more than $2 billion in unfunded pension liabilities (i.e. pension debt). These pension solvency challenges are already straining Arkansas budgets, and if left unaddressed could put the state’s ability to honor pension promises made to public workers at risk, while also passing the debt and problem onto future generations.

Ever since the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, followed by the 2007-08 financial crisis and recession, many U.S. jurisdictions have found themselves perpetually grappling with rising public expenditures amidst tepid budget growth. Arkansas is no exception.

Luckily, Arkansas is among the states that are enjoying positive net-migration, which could likely increase its chances of replenishing state coffers with greater tax revenues in upcoming years.

One might expect such an uptick to adequately fund schools, road maintenance, and other public needs, but, unfortunately, in virtually all jurisdictions the rising costs of public pensions are increasingly crowding out other public priorities.

Last year alone, state employers contributed as much as $275.8 million (mostly in taxpayer dollars) into the Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System (APERS). Likewise, a considerable share of state funds in 2020 and beyond are likely to bypass many crucial public priorities to service the unfunded portion of pension liabilities.

“What is our plan for the unfunded actuarial liability?…[I] have heard one board member say it is zero. I don’t know if it is zero or not,” asked David Hudson, a Sebastian County judge, during the meeting of APERS pension board trustees, which featured pension discussions and a presentation from Callan Associates, the pension plan’s investment consultants.

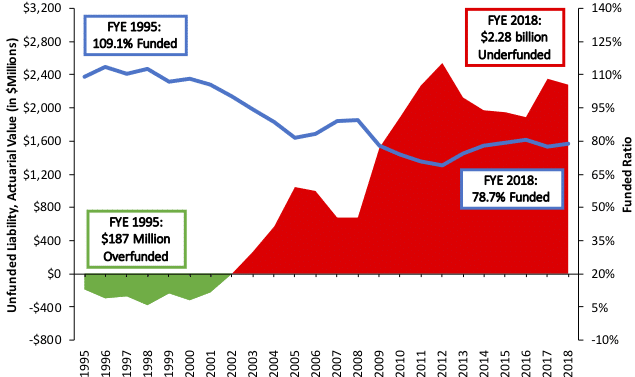

That’s a great question, because APERS’ unfunded pension liability is obviously above zero, well above it, in fact. Last year PERS was $2.28 billion (on an actuarial basis) in the red and only 78.7 percent funded (see graph below).

Figure 1: Arkansas PERS Historical Solvency

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of Arkansas PERS valuation reports and CAFRs.

Trustee Larry Walther, director of the state Department of Finance and Administration, said during the same meeting that he wants to work toward reducing unfunded liabilities “toward zero again.”

“That’s going to require some work on our part,” Walther added. In the last session, most of the trustee-backed bills to reduce the system’s unfunded liabilities and bend the pension cost curve down over time failed to clear the legislature.

How would tackling pension debt save costs for the public?

The logic is simple: when unfunded liabilities grow, it leads to higher contribution requirements because like any debt, once pension debts accrue, they need to be paid down along with any accrued interest. Because well-funded pension plans—like those in Wisconsin, South Dakota and Tennessee—have consistently kept pension debt under control, they are only required to pre-fund actual pension benefits without making additional pension debt payments, which plays into maintaining a low impact on state budgets.

But, that’s an enviable position not enjoyed by Arkansas and many other states. For APERS, the main culprits driving APERS debt are: poor investment returns (relative to overly optimistic return assumptions), followed by benefit increases, changes in actuarial assumptions, interest accrued on past pension debt exceeding amortization payments, and spurious actuarial assumptions on demographic changes (including overestimating retention rates and salary increases given).

Figure 2: Factors Driving APERS Pension Debt, 2002-2018

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of Arkansas PERS valuation reports and CAFRs

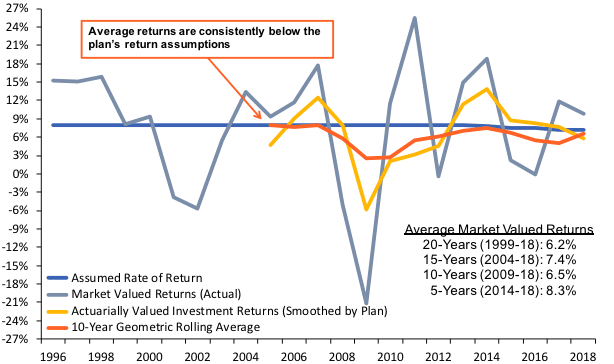

Investigating the causes of pension debt can assist governments in identifying the main culprits that increase risks of insolvency, allowing them to effectively correct their course. For example, many pension plans started adjusting both their rate of return assumptions and discount rates (often, but mistakenly, set to equal each other) in the wake of the financial crisis so as to reduce the risk of future underfunding a recession. According to a Milliman analysis of major public pension plans, the median discount rate fell from 7.75 percent in 2013 to 7.25 percent in 2018. These revisions also fall in line with sober projections from financial advisors.

Last year, APERS joined this trend by changing its assumed rates of return to 7.15 percent, which was a step in the right direction. However, the revised target still exceeds even the plans’ historical returns —APERS investments averaged out only to 6.5 percent and 6.2 percent (geometric mean) returns over the past 10 and 20 years, respectively.

Figure 3. APERS Investment Return History, 2001 – 2018.

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of Arkansas PERS valuation reports and CAFRs

And while it seems that APERS has a chance to hit its return target this year, ending Q3 (January to March 31, 2019) with 9.65 percent return, a rough and tumble play with capital markets this year may yet put another dent in the financial health of Arkansas public pensions. This matters as investment return proceeds are instrumental in shaping both the pension solvency and anticipated contribution requirements.

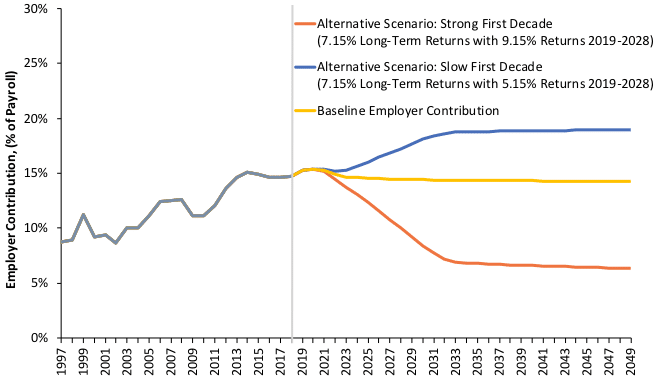

For example, based on the Reason Foundation Pension Integrity Project’s actuarial projections of APERS funding returns averaging out 200 basis point above and below the 7.15 percent return assumption over the next decade, portend significant volatility in future contribution requirements (see graph below).

Figure 4. APERS Employer Contributions Under Different Return Scenarios

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of Arkansas PERS.

Arkansas public pension trustees are likely to continue their discussions on viable recommendations to fix public pensions for the 2021 regular legislative session.

Reducing—or even better, eliminating—unfunded pension liabilities could be one of the best bets in improving the solvency of the state’s retirement systems over the long-run. Arkansas wants to ensure that it continues attracting more people and talent to the state, so it would be well-served to alleviate unnecessary strain on future taxpayers and prevent erosion of the state’s fiscal position.