Conventional wisdom has it that without the ability to deduct mortgage interest from federal taxes, homeownership rates and housing prices would tumble. Worse, middle class families would be relegated a fate worse than foreclosure: renting. Two decades ago, these dire predictions may have had some relationship to reality. But in recent years, the middle class has seen its share of the mortgage interest deduction (MID) steadily erode, undermining the political case for retaining the subsidy.

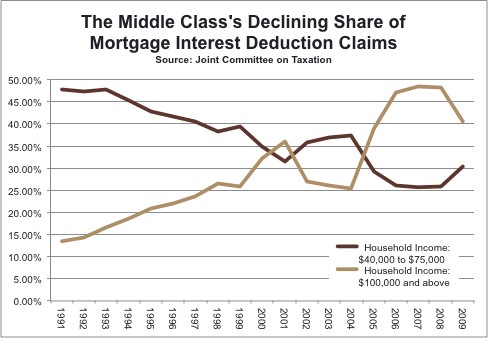

In 1991, households earning near the inflation-adjusted median income of around $50,000 were 48 percent of those benefiting from the MID (see nearby chart). That share has fallen to 30 percent in 2009, while at the same time the portion of households claiming the MID with six-figure salaries or higher has tripled from 13.5 percent to 41.5 percent.

In 1991, households earning near the inflation-adjusted median income of around $50,000 were 48 percent of those benefiting from the MID (see nearby chart). That share has fallen to 30 percent in 2009, while at the same time the portion of households claiming the MID with six-figure salaries or higher has tripled from 13.5 percent to 41.5 percent.

What caused this trend? The answer lies in understanding who really benefits from the mortgage interest deduction, and how much the specialized subsidy is worth.

In 2009, only one-fourth of taxpayers in 2009 claimed the mortgage interest deduction. And this has been a relatively stable historical trend, with between 21 and 26 percent of taxpayers claiming the MID each year since 1991. Of those few who do benefit from the MID, most are households in the top income brackets and younger individuals with large mortgages who have not paid off much of their loans. Families where the head of household is between 25 and 35 years-old with incomes over $250,000 have, on average, a $7,711 deduction from mortgage interest, compared to a similar household with earnings between $40,000 and $75,000 a year, and taking an average $571 deduction. Meanwhile, low-income families, seniors, and Americans without mortgages gain virtually nothing from the program.

Many Americans believe the mortgage interest deduction allows them to deduct their entire interest payments from their tax bills-and make home purchasing decisions based on that misunderstanding. Instead, the MID lowers taxable income. Tax bills are lowered, but that’s a much smaller benefit.

When considering the actual tax savings of the mortgage interest deduction, the benefits to the middle class become even more meager. The average tax savings for households with income between $40,000 and $75,000 is just $152 a year. That’s $12.66 a month. Compare that to the highest earners, those making $200,000 or more, who see an average of $1,862 a year off their tax bills because of the MID benefit.

One reason often cited for preserving the mortgage interest deduction is the belief that it helps increase the homeownership rate. But as it turns out, the MID is an inefficient tool for increasing homeownership. Since 1994, the homeownership level has gone from 64.2 percent up to 69.2 percent in 2004 and then down to 66.4 percent today. The recession and collapse of the housing market is largely responsible for the decrease in homeownership. If the mortgage interest deduction were driving people to buy homes we would expect to see some correlation between homeownership rates and the use of the deduction, but we don’t. The total mortgage interest deduction subsidy has grown from roughly $50 billion to $80 billion since 1994 with little impact on homeownership levels.

This is because those households that rent but would prefer to own a home-if they had just a bit more financial flexibility-are typically low-income families. And if they bought a home they would be much less likely to itemize their deductions and claim the MID because they are low-income in the first place. For median income families that do itemize, a $12.66 per month tax savings is not likely to be the difference between affording a mortgage payment and renting. As a result, rather than increasing the homeownership rate, the primary impact of the MID is to increase the amount spent on housing by consumers who would likely choose to own a home anyway, subsidizing spending on housing rather than homeownership.

The MID also encourages housing consumers to use debt rather than their own assets to finance home purchases. And by creating favorable tax treatment for housing compared to other investments, the mortgage interest deduction encourages individuals to over-invest in housing, arguably one of the main causes of the recent housing bubble.

But wouldn’t eliminating the mortgage interest deduction amount to tax hike? In fact, the impact would be limited, since 75 percent of Americans don’t even claim the deduction each year, meaning the vast majority of people will find their tax bills unchanged.

In a new study I co-authored with economist Dean Stansel, we calculated that if an MID repeal were combined with a proportional reduction in tax rates to make it revenue neutral, average rates could be reduced by 8 percent for everyone. The majority who don’t use the mortgage interest deduction would see a tax cut and the few that do would not see too dramatic an increase in taxes.

The original goal of the mortgage interest deduction was not to help the middle class or promote homeownership. It is an accident of the tax code, left over from the original institution of the income tax in 1913, and deliberately ignored during President Reagan’s tax reform in 1986 for political reasons. A revenue-neutral change would benefit all taxpayers in the form of lower rates and less distortion while the limited adverse effect of the elimination of the deduction subsidy would only pertain to a few. There is no reason to keep it in the tax code, and plenty of cause to remove it.

Anthony Randazzo is director of economic research at Reason Foundation and co-author of the new study: “Unmasking the Mortgage Interest Deduction: Who Benefits and How Much.” A copy of the fully study (PDF) and a four-page summary (PDF) of the study can be found at Reason.org. This column first appeared at Reason.com.