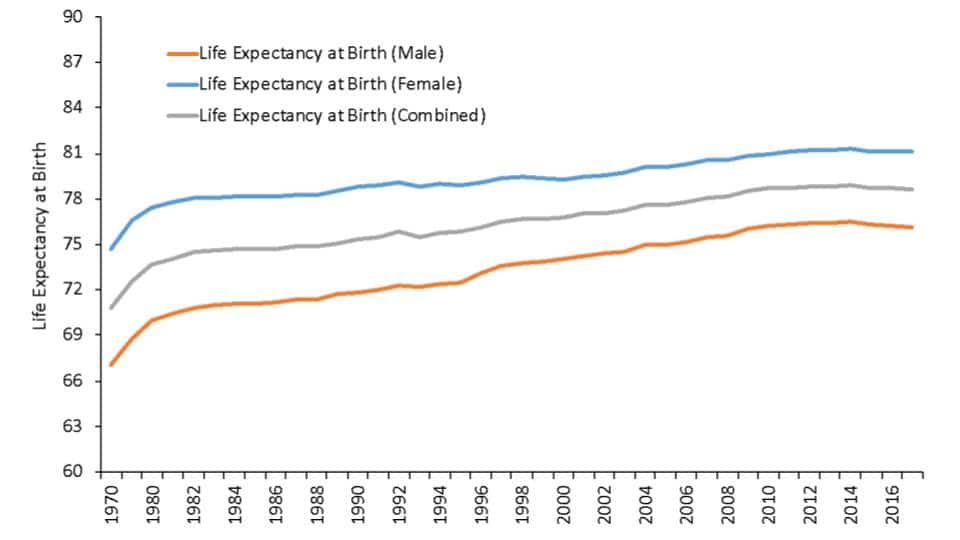

Reversing a secular upward trend, U.S. life expectancy has declined for three years in a row: from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017, the latest year for which data is available (See Figure 1).

This trend is concerning on a variety of fronts and experts are also examining ways it impacts the financial pressures on social insurance and pension systems obligated to pay lifetime benefits. In most cases it would seem straightforward: the shorter beneficiaries live, the fewer benefits they receive. But for public sector employee pension plans, the financial implications of this life expectancy trend are less clear.

Figure 1: Life Expectancy at Birth, U.S.

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis based on the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2018.htm?search=Life_expectancy.

Drilling deeper into the vital statistics, we see that although life expectancy at birth has declined by 0.3 years, life expectancy at the traditional retirement age of 65 has held steady at 19.4 years and has remained unchanged for those aged 55 and 60. This is explained by the fact that the increase in deaths is occurring among adults aged 25 to 64 years old. According to Brookings Institution research, more people in this age cohort are struggling with drug and alcohol dependence and are committing suicide at higher rates.

As noted in the literature on “deaths of despair,” the biggest impact has been felt by non-Hispanic white males between the ages of 45 and 54. In this group, the death rate from alcohol, drugs, and suicide has more than doubled since the beginning of the century, reaching a rate of 91.6 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

But once one reaches retirement age, longevity, and, thus the length of benefit eligibility, remains the same. Put another way, mortality rates among those around, or above, the retirement age did not change much. That said, more deaths among those aged 45 to 54 could reduce the initial pool of those eligible for pension benefits, but are those deaths impacting the membership of public employee pension plans?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, roughly 51 percent of private- and 83 percent of public-employees participated in a workplace retirement plan in 2017. If the trend toward greater middle-aged mortality was affecting pension-eligible workers, it should have affected a larger share of public workers. But it is not clear if this trend includes a significant number of government employees at all.

For example, deaths of despair are most prevalent among less-than-college-educated white men. However, public employees have higher education levels, on average, than private-sector employees. Further, despair tends to be concentrated among those who are either unemployed or out of the labor force, and thus not likely participating in public employee pension systems. Further, higher job security in the public sector might be expected to limit despair and the premature deaths it causes.

While life expectancy among those aged 55-65 has not changed overall, mortality rates do seem to deviate among public and private workers. For example, a 2015 study by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (CRR) analyzed data from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study (NLMS) and found that women and men in the public sector who reached ages 55-64 experienced 1.2 percent and 0.6 percent fewer deaths, respectively, than their private-sector counterparts.

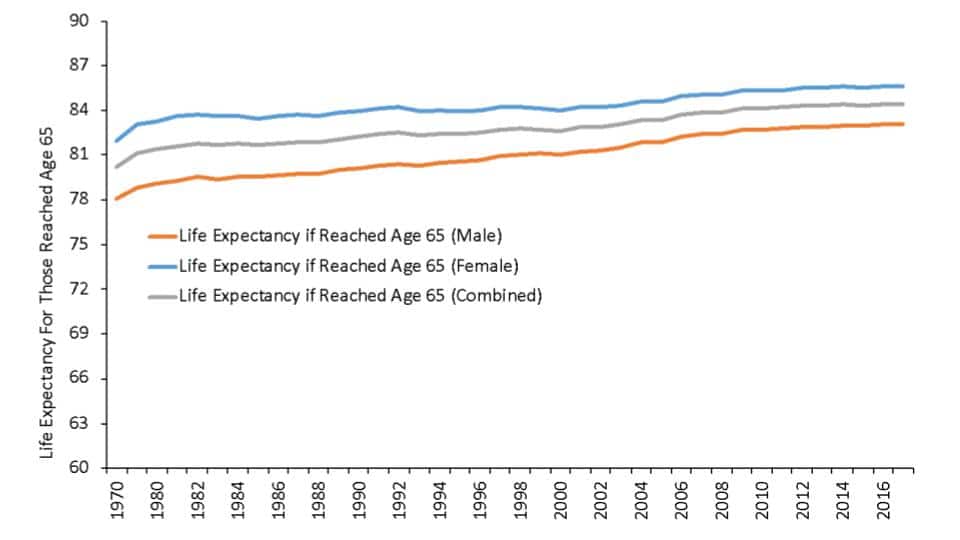

Also, as my Reason Foundation colleague Anil Niraula reported, a recent Society of Actuaries (SOA) mortality study found that public sector employees have longer life expectancies than the general population. For example, “Female and male teachers who reach age 65 are expected, on average, to live to 90 years and 87.7 years, respectively” — exceeding the expected 84.4 years achieved by the general population (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Life Expectancy at age 65, U.S.

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis based on the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2018.htm?search=Life_expectancy.

Per the CRR study cited above, education may be the key ingredient that explains the difference. Their conclusion was simple: 1) public sector workers, on average, are more educated than private-sector workers; and 2) more educated people have lower mortality.

But although public sector retirees are underrepresented among the “deaths of despair” population and live longer than private-sector retirees, it is possible that the rate of life expectancy increase is slowing for this population segment. To have a firmer understanding, we may need to wait a few years until SOA updates its public employee mortality tables in four or five years.