A recent study written by University of Michigan researcher Roland Zullo claims that the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) spent $90 million more (roughly double) on contracting engineering services with the private sector compared to what government workers would have cost to perform the same services.

However, the origin of the work, its methodology, and the lack of available data raise serious questions about the findings and make the cost comparisons problematic. At best, the study can be said to provide an unclear answer to a narrow question.

According to the study, the lion’s share of the cost difference lies in “overhead” costs. While MDOT employees are assumed to have a 10 percent overhead, the state says this is “conservative, and in most circumstances will understate the actual indirect costs experienced by agencies.” Contractor overhead costs, in Zullo’s words, “exceeded their charges for direct labor. Overhead expenses by the private contractors exceeded their charges for direct labor. When taking into account overhead and profit, the cost of private consultants became roughly double the cost of comparable MDOT output.”

But where is the data for this claim? Since Zullo provides no actual figures relating to contractor overhead (only a bar chart with a large shaded area representing contractor overhead costs that appears to almost double wages), it’s difficult to say what the study’s overhead total for contractors includes. Indeed, other than an assumption on the cost of health benefits, the only dollar amounts that appear in the entire seven-page report are basic descriptive statistics: average contract amounts and estimated totals for in-house and contracting work over the three-year period.

The report’s main methodology matches in-house engineering consultant positions to their contractor equivalents. While the author notes that the MDOT employee solely responsible for the matching exercise has “over 30 years of experience,” the author failed to disclose in the study (unlike a Detroit Free Press article that flagged the issue) that the employee in question is also member of Local 517M, the union affected by the contracting practice in question.

The data used for the study presents its own problems: The author’s research partner—the Service Employees International Union (SEIU, of which Local 517M is one office)—purchased the data for the study via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, which was said to be a “random” sample of engineering consulting contracts, but no information was given on the size or characteristics of contract data excluded from the originally purchased sample. Zullo and the SEIU obviously cannot be blamed for not possessing the missing contractor data, but without any understanding of the size or the contractor data excluded from the study, the applicability of the findings to all engineering contract consulting positions is questionable.

Zullo then made the random sample into a smaller random sample that represents only 23 percent of the original. Though, to his credit, he does provide some descriptive statistics from data excluded, which appear to be close to what the author excluded from the original random sample. Regardless, the amount of contracting data excluded by the original random sample provided by the FOIA request remains a mystery, as do the methods employed to make the data “random.”

Even giving the author the benefit of the doubt with respect to the sample of contractor data used, making cost comparisons of services provided between public and private actors are difficult to fine-tune and include guesswork. For starters, governmental agencies and private organizations use different accounting methods, thus making line-by-line cost comparisons difficult.

Another concern is that the three-year time period studied gives short shrift to post-retirement costs of government workers. While the author’s 7 percent of pay assumption for pension contributions appears reasonable for the state’s defined-contribution plan beneficiaries (mostly, those hired after March 1997), at least some active state employees at MDOT remain in a legacy defined-benefit plan for which 7 percent estimates are highly optimistic if the costs of both pre-funding current pension benefit accruals (the “normal cost”) and the cost of amortizing unfunded pension liabilities are fully covered on an actuarial basis. The latest comprehensive annual financial report for the Michigan State Employees’ Retirement System indicates an employer contribution rate in excess of 20 percent of payroll for this particular cohort of employees.

State workers receive retirement health care benefits—which aren’t accounted for in the study’s assumptions of around $4,200 per year—also exceed 20 percent of payroll in terms of the employer contribution rate, according to the same report. The Zullo paper cites a $12,500 figure per full-time equivalent worker for the three-year period, which only reflects health care plans for current employees, without any retirement health benefits.

Failing to consider fully loaded retirement costs in the public sector inherently stacks the deck against a private contractor with respect to cost comparisons.

But even if costs are accurately compared between public and private providers of government services, the quality of service must be measured as well. For many outsourcing functions, performance standards monitored by government actors can be included in contracts to ensure service quality, by financially punishing contractors who fail to meet such standards.

While the author doesn’t state so, it appears that monitoring costs are included in contractor “overhead,” but it is unclear if similar monitoring services for in-house employees are included. They should be. If we’re going to require performance assessment and management for contracted services to ensure taxpayers are getting the deal they paid for, we should expect public agencies to similarly invest in performance measurement/management for the exact same reason. If government workers cannot commit to being held to the same accountability standards as contractors, then why would their quality of work be equivalent?

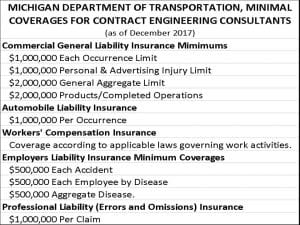

One way to partially assess performance resides how work risk is assessed and indemnified by insurance markets. For state employees, the state mostly assumes all such risk itself. In Michigan, private engineering consultants seeking contracts are required to hold a host of coverages for themselves and, in the case of general liability insurance, policies must also include an endorsement to add “’…the State of Michigan, its departments, divisions, agencies, offices, commissions, officers, employees, and agents’ as additional insureds.”

While the study does account for Workers’ Compensation (1 percent of wages), it fails to account for the costs of the other coverages and the benefit of transferring general liability and other insurance risks to contractors.

Further, the study compares workers with similar levels of experience (years on the job) but not similar skillsets. MDOT requires its civil engineers to hold a four-year degree in the field; private consultants often obtain Master’s degrees in transportation engineering requiring six years of school. Workers with more advanced degrees receive higher pay based on specialized skillsets such as National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) modeling, which four-year degree programs do not provide. In addition, since specialized consulting is needed in unpredictable patterns, it probably does not make sense for MDOT to hire full-time employees for such hard to predict tasks, as opposed to hiring qualified contractors for limited durations. Hiring contractors who possess advanced specialization, when needed, is cheaper and provides better quality services than the DOT could produce by itself.

It is certainly possible that Michigan may have overspent on engineering consulting contracts over a three-year period, but this particular study lacks the rigor needed to make such claims. By making assumptions that understate governmental costs and provide little transparency with respect to data used, the Zullo study can best be said to suggest that the state may have overpaid for engineering consulting services over the period in the study. A comprehensive and transparent analysis would be required to validate that claim.