A pension fund’s assumed rate of return is meant to represent the most accurate average long-term return on assets, but recent events in New Jersey are a clear demonstration that this assumption can also be the product of political factors that go beyond accurate financial projections.

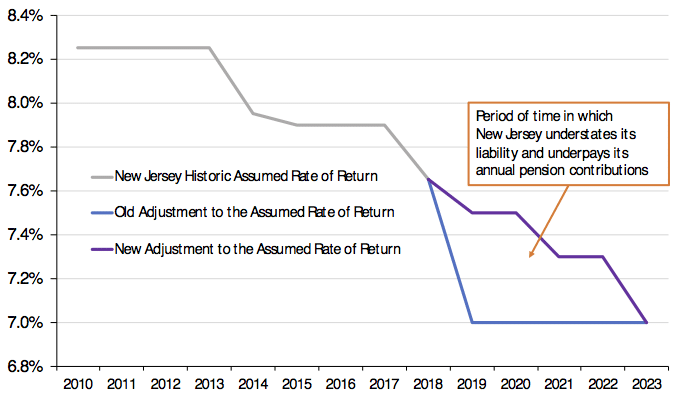

The state’s new acting State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio—who has yet to be confirmed by the Senate—announced her intention to roll back the previous administration’s decision to lower the assumed rate of return of the state’s struggling pension system last fall. In November just before leaving office, then-Gov. Chris Christie’s administration enacted a policy to lower New Jersey’s expected rate of return from 7.65 percent to 7.0 percent, effective fiscal year 2019. This move was consistent with previous actions of the administration, which had already lowered the rate twice from the original 8.25 percent.

The move to a 7 percent assumed return is also in line with nationwide trends that recognize the emergence of a “new normal” in what pension funds are able to earn from investment assets.

As is the case with any lowering of the assumed rate of return, the move would have increased the annual required contributions towards the pension fund. New Jersey already makes payments severely below the annually required amounts, but this change in policy would have been a positive step in the direction of more accurately acknowledging the true liability of the state’s struggling pension system.

The change to a 7 percent assumed rate of return stirred up some controversy, however, as it represented a large drop that was enacted just one month from the end of Christie’s time in office. The drop to 7 percent would have increased the state’s 2019 contribution by $390.3 million, or $234 million if they continue to pay just 60 percent of the required contribution. Total contributions from New Jersey’s more than 460 municipalities would have gone up by $422.5 million. The increases would have been particularly difficult on municipal budgets, as they are unable to pay below the required amounts as the state does.

To minimize the drastic increase in required contributions, Treasurer Muoio will roll back the immediate change and instead lower the expected rate of return gradually over five years. This move is similar to what California’s Public Employees’ Retirement System (the largest pension system in the country) is doing. The rate for fiscal year 2019 will now be 7.5 percent (still a reduction from the current 7.65 percent. The rate will then be lowered in fiscal year 2021 to 7.3 percent, followed by a final reduction to 7.0 percent in 2023.

Explaining the policy change, Muoio said the gradual change will help “mitigate the undue stress” on state and municipal budgets.

A gradual adjustment to a 7.0 percent assumed rate of return may be more palatable for policymakers and budget directors than an abrupt one, but to label it as a method to alleviate state and local budgets in the short term fails to acknowledge the fact that those savings only represent funds that will need to be paid later in future budgets.

Since there appears to be a consensus that using a 7 percent rate of return is the most responsible way to calculate New Jersey’s required payments going forward, every fiscal year in which a higher rate used will theoretically result in paying below the necessary amount, adding even more to the state’s unfunded liability.

New Jersey’s Assumed Rate of Return, FY 2010-23

This case brings up an interesting question associated with making changes to the assumed rate of return: is the decision to lower the rate gradually based on sound accounting principles? In the case of New Jersey, they acknowledge the “correct” rate of return as 7.0 percent but will spend the next five years calculating their liabilities and required payments based on a higher rate. In short, it is an accounting gimmick that will synthetically present the system’s liability as less than it really is.

This is not to say the stress on the state and local budgets isn’t real during drastic changes in the pension fund assumed rates of return. These factors must be considered and ought to be mitigated when necessary. Last year, Kentucky lowered its assumed rate of return from 7.25 percent to 5.25 percent. The change wasn’t made gradually but in one jump. Kentucky’s large change didn’t ignore the crowd out that would inevitably occur from the increased annual required payments to the pension fund. Instead, it simply acknowledged the rate of return that made sense for the fund’s risk and asset characteristics, and are now considering other methods to alleviate the stress on the commonwealth’s budgets that resulted from the adjustment.

There is nothing wrong with phasing in the cost of a lowered assumed rate of return, in fact, it is oftentimes necessary. But using the assumed rate itself as a tool to this end undermines the entire purpose of this assumed metric. The rate of return is meant to be the most accurate projection possible, keeping in mind a fund’s asset allocation and risk profile. If experts and policymakers have determined a lower rate to be more accurate, the change ought to be made immediately. Any gradual change, as New Jersey is now doing, is a case of making the accounting subservient to politics. Policymakers, therefore, should apply a new assumption right away and seek out other methods to phase in the added costs.

Despite rolling back the previous policy, New Jersey continues to maintain a policy that eventually lowers the assumed rate of return to its proper level. Using an assumption in the transition years that is knowingly above the proper level is dishonest to the workers, retirees, and citizens of New Jersey, but this policy will be short-lived. By 2023, the plan’s reports will show the most accurate calculation for the state’s pension liability and policymakers will be in a better place to address the full magnitude of the promises made to public workers.