Proponents of pension benefits often argue that this system helps recruit and retain public employees. In truth, most public employees do not remain in their roles long enough for their retirement benefits to vest, and only a small minority of those who remain accrue significant benefits.

This analysis focuses on 12 state-run public pension plans, representing two primary groups of public workers—teachers and general employees. These plans were chosen primarily because they are relevant to the Pension Integrity Project’s engagement with policymakers to improve the solvency and efficiency of public retirement plans. Politically, these pension plans are all in red or purple states, but this information is relevant to all states because all public pensions are experiencing similar trends in employee separation, and there is little variation in the assumptions used to estimate costs.

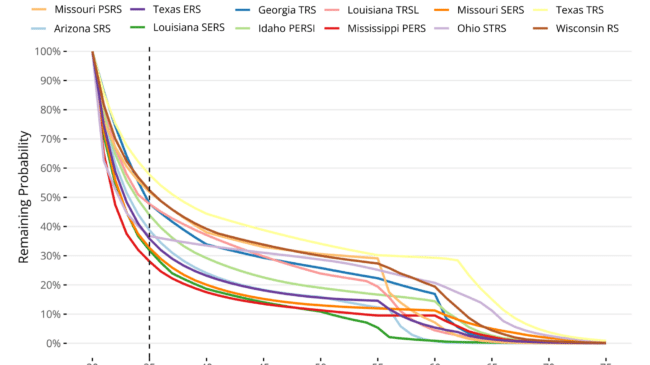

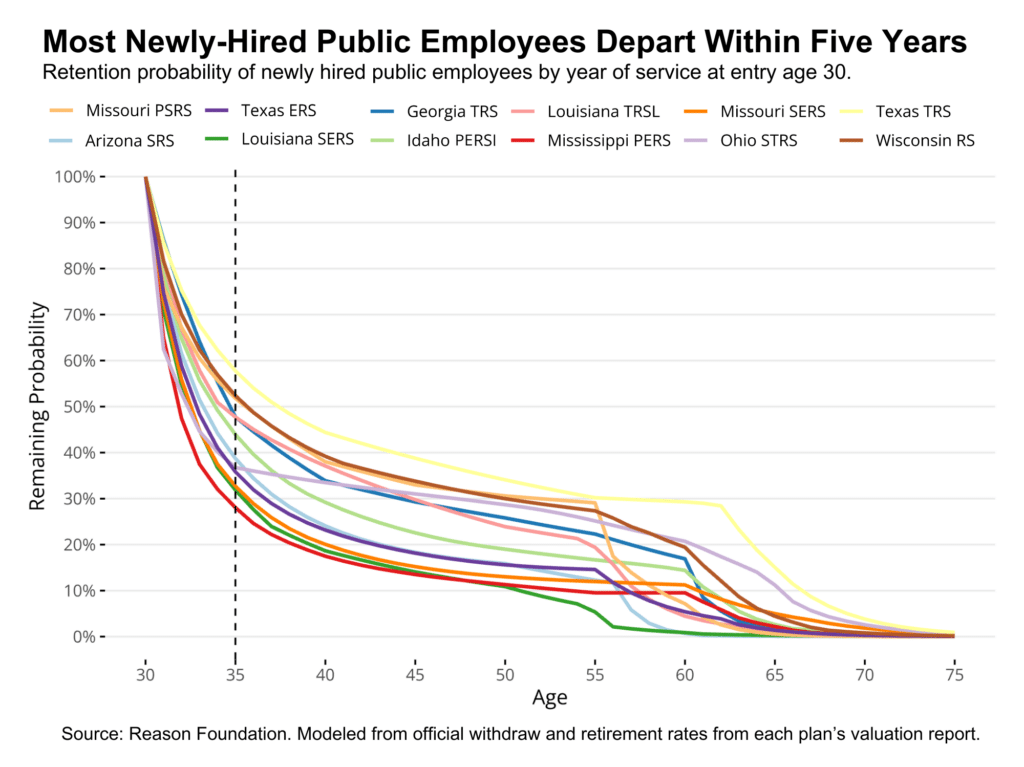

We analyze expected withdrawal and retirement rates from these 12 pension systems to find the likelihood of a newly hired public employee (age 30) continuing in various retirement systems over time. Given typical vesting periods for defined benefit (DB) pensions, our analysis shows that most newly hired public workers are unlikely to receive any significant return on their pension contributions.

This graph plots retention probability derived from the withdrawal and retirement rates declared by actuaries of the 12 pension plans in our sample. These rates, which are determined based on historical data and future expectations for each plan’s workforce, reveal much about the dynamics of public employment.

Finding 1: Public employees often leave before vesting

A newly hired employee with a DB plan will likely not remain in their role long enough for their retirement benefits to vest. Combining the 12 plans reviewed, approximately 62% of public workers leave before vesting in their pension plan.

Consider the Teacher Retirement System, TRS, of Texas, which has the highest assumed retention rates in this sample. Even though the plan vests benefits after only five years of service, only 57.8% of newly hired members entering at age 30 will still be in service by this time.

Conversely, the Public Employees’ Retirement System, PERS, of Mississippi has one of the lowest assumed retention rates in the sample and yet requires eight years to vest pension benefits. Mississippi’s actuarial assumptions indicate that only 20.4% of age-30 new hires are expected to remain in service until then.

According to a 2022 Equable study, the average minimum vesting period for a state-defined benefit pension plan is 6.9 years. Public safety plans, on average, require eight years of service, with several plans stipulating 10 years or more of service for retirement benefits entitlement. The average pension vesting requirement for teachers and public school employees is 6.4 years. This means that, across the board, most public employees must often serve around seven years to fully vest their benefits. However, for the plans in our sample, only 35.9% of new hires reach seven years of service.

In short, only a minority of new hires into a plan remain long enough to vest.

Finding 2: Approaching vesting does not increase retention

In the retention curves, we do not see a pronounced change or plateau as employees approach or pass their vesting milestones. This indicates that—according to actuarial estimates based on historical data—public employees do not stay marginally longer in their roles to ensure they vest in their pensions.

This makes sense from the point of view of employees who have not been in their roles for decades because their pension benefits, even if fully vested, are often only accessible far into the future and are insufficient to sustain them through retirement. Most growth in a defined benefit pension occurs in the last few years of service. As the retention graph shows, a minority of newly hired public employees reach 15-plus years of service. For the 12 plans studied, only 24.8% of workers reached the 15-year mark. For those fully vested but not close to 15 years of employment, the expected annual retirement benefit is not enough to provide adequate retirement security, and each additional year of service only slightly increases that amount.

Vesting requirements do not appear to impact public employees’ behavior, suggesting that factors other than pension benefits likely influence their decisions to stay or leave public employment.

Finding 3: Turnover is concentrated among new employees, so pension enhancements are unlikely to improve recruitment and retention

The retention curves illustrate that turnover is heavily concentrated among new employees, with the sharpest drops in retention probability occurring in the first few years of service. Most workers who depart public employment tend to do so early in their careers.

The curve tends to plateau after a decade or two of service, revealing that employees who served for longer tenures are increasingly likely to stay until retirement.

Thus, enhancements to retirement benefit formulas (such as multipliers or years of service) are likely counterproductive to improving public employee turnover. Such benefit enhancements reward those later in their public careers, where retention probability has stabilized.

Since most turnover in public offices is concentrated among newer, less-tenured employees, employers should focus on improving the early years of employment to reduce turnover. Addressing commonly cited grievances and providing desired benefits—such as flexible schedules, remote work options, or higher salaries—are likely more effective in retaining employees.

Finding 4: Only a minority of public workers tend to earn significant pension benefits

Finally, this analysis demonstrates that only a minority of public pension participants will earn substantial lifetime retirement benefits. Most new hires—who leave before vesting—will only get back their contributions upon leaving, but not the significant amounts contributed by their employers to their retirement plans. Even among public workers whose pension benefits do vest, most will go with meager lifetime guarantees that will be significantly diminished by inflation by the time they reach retirement age.

Pensions are designed to accommodate career employees, with benefits becoming most optimal in the later years of a long stint working as a teacher or public worker. However, as this analysis demonstrates, this situation is the exception for the modern public employee, not the rule. Proponents of pensions argue that pensions motivate employees to stick around, but with lengthy vesting requirements and the undeniable majority of new hires leaving before they can enjoy the full advantages of a pension, this is more akin to gating off crucial retirement benefits for most public workers.

With most newly hired public employees leaving before vesting in pension plans and turnover concentrated on the first few years of service, it’s clear that current structures are misaligned with today’s employment patterns. Policymakers should keep the revealed preferences of public employees in mind as they design more sustainable and effective compensation and pension systems that keep and reward talent in the public sector.