Public pension funds nationwide use different fiscal year start and end months. When analysts and policymakers compare yearly returns among public pension funds, the different fiscal years are often overlooked. The disparity in end months can significantly influence a pension fund’s reported investment performance, skewing single-year comparisons in volatile market conditions and obscuring the true disparities in financial outcomes of public pension systems. Before comparing the investment returns of pension funds, it is essential to understand the impact of fiscal year-end months.

This analysis uses data from the Reason Foundation’s 2024 Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report, which is built from data on 296 public pension plans that manage 88% of the total estimated assets within U.S. public pensions.

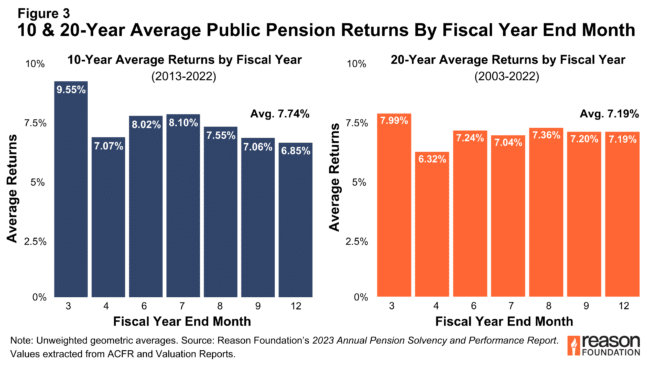

Figure 1 plots the number of public pension funds that filed in each fiscal year-end month for 2022.

In Reason Foundation’s database, 67% of the public pension plans end their fiscal years (FY) in June, 22% end their fiscal years in December, 6% end them in September, 2% in August, 1% in July and April, and 0.7% in March (representing solely New York’s public pension plans).

The problem with same-year comparisons: Using FY 2022 as a case study

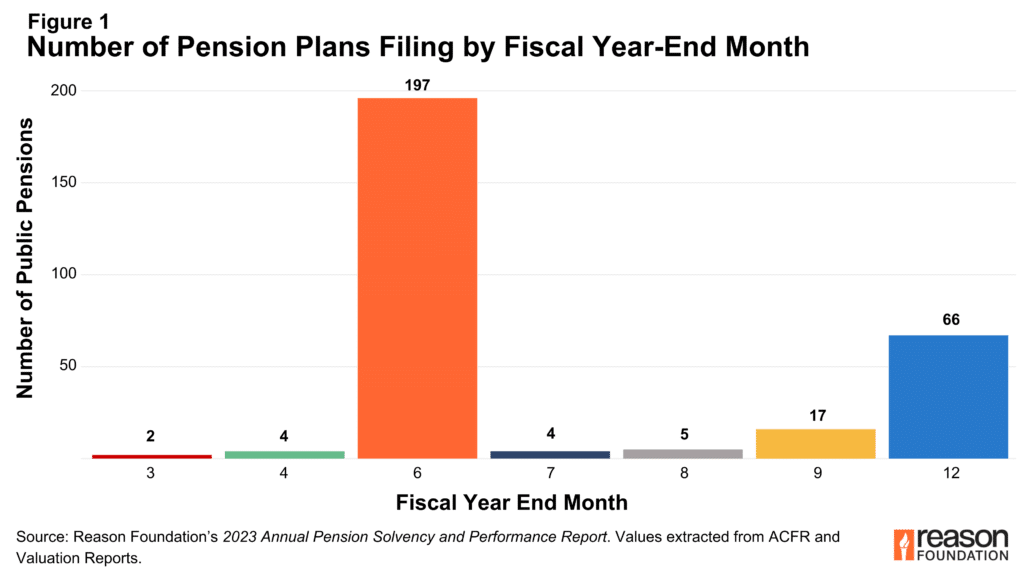

The year 2022, the latest year of complete data available for public pension systems, offers a case study into how fiscal year-end timing can affect reported investment returns. The prior year was characterized by historic levels of market volatility driven by inflation, rising interest rates, and supply chain disruptions. Early in 2022, markets corrected sharply as the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates in response to inflation. As Figure 2 displays, pension funds filing at different points throughout the year experienced vastly different market conditions, illustrating how same-year comparisons of investment performance between pension plans are problematic.

For pension funds whose fiscal years ended in March 2022, the average rate of return was an impressive 9.51%. By contrast, those that ended in June 2022 reported an average return of -5.56% for the year, while those with a December fiscal year-end reported an average return of -10.84% for 2022. The average rate of return declared by public pension funds in our sample was -6.89%.

This wide disparity demonstrates that pension funds closing their books at different times within the same calendar year can capture vastly different market environments, revealing the need to understand the timing of financial reporting when analyzing pension performance and putting into question the usefulness of yearly pension investment rankings.

Do differences dissipate in the long run?

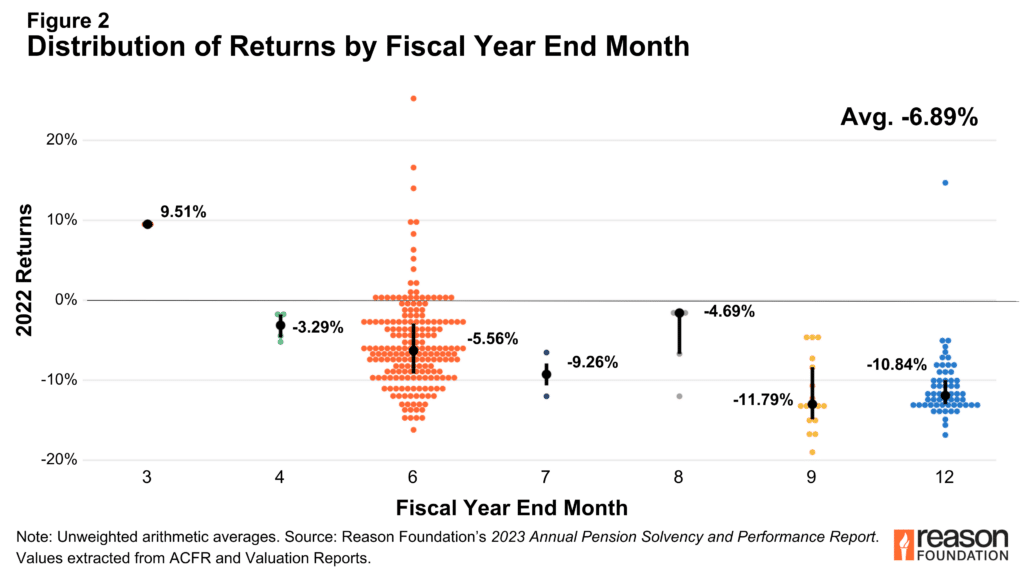

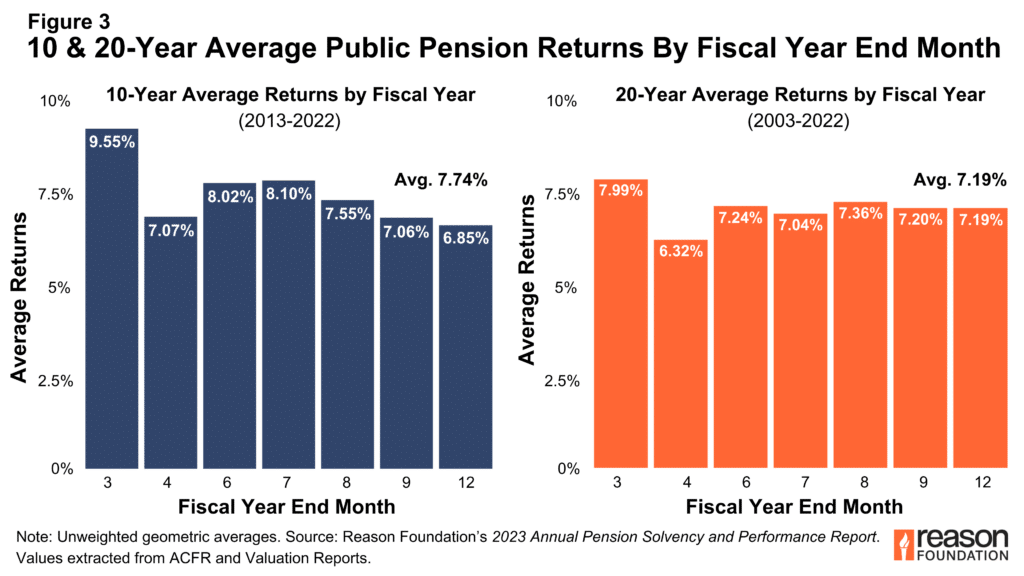

If the disparities observed in Figure 2 are attributable to capturing different periods of market rallies and sell-offs—i.e., booms and busts—we should expect the differences observed in Figure 2 to dissipate in longer time horizons. For example, public pension plans that avoided capturing a large share of market downturns in FY 2022 should then have them reflected in either their FY 2021 or FY 2023 returns and so forth.

Figure 3 reveals that the disparities in investment returns observable in Figure 2 dissipate in the long run, but some differences remain. Pension plans filing in December tend to report lower rates of return than those reporting in June, and plans reporting in less common reporting months tend to perform near the average, except for those filing in March.

Given the small number of plans that report in any month besides December and June, it is hard to make decisive judgments about whether long-term differences are attributable to fiscal year-end month and returns. It is most likely a feature of the plans, not meaningful cohort trends.

For example, the disparity in returns for plans ending in March stems from only two plans in our sample report investment returns during this month. Both are from New York: the New York State and Local Employees Retirement System and the New York State and Local Police and Fire Retirement System. These public pension plans consistently outperform most other pension plans across all time horizons. Therefore, the elevated average investment returns observed in March are not a consequence of fiscal year-end timing but are instead attributable to the strong investment performance of New York’s pension systems.

Pension returns are skewed by fiscal year-end timing, but long-term results converge

Fiscal year-end month is a significant factor in short-term return variability. However, these differences disappear over a longer time horizon, reinforcing the conclusion that fiscal year-end timing is not a determinant of long-term pension investment performance.

Comparing same-year returns of pension plans with different fiscal year-end months, such as June versus December, is inappropriate and can lead to misleading conclusions due to fluctuations in market conditions within the same calendar year. For performance assessments of plans with different fiscal year-end months, comparing 10- or 20-year investment return averages is more appropriate.

Policymakers, researchers, consultants, and anyone who desires to comment on the investment outcomes of pensions should examine this dynamic. Fiscal year month-end matters tremendously when comparing yearly returns, but this bias fades away over longer time horizons.

The data in this article are extracted from the first iteration of Reason Foundation’s Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report, which compiled financial measures declared in static PDF financial reports from 296 public pension plans, of which 192 are state-administered pension systems, and 104 are local. The full report and database are here.