Concerned over rising pension contributions, policymakers in Chicago are contemplating borrowing millions in the form of pension obligation bonds (POBs). However, city leaders may ultimately reject the idea as many other state and local governments with underfunded public pensions have found POBs bring long-term risks that can in fact worsen—not improve—a government’s fiscal health over time.

To say that Chicago’s pension systems for public employees have solvency concerns would be an understatement. Last year, for example, the Chicago’s two largest pension funds: Municipal Employees’ Annuity & Benefit Fund of Chicago (MEABF) and Chicago Teachers Pension Fund (CTPF), were just 28.0 percent and 46.6 percent funded, respectively (as reported under current GASB accounting rules). The same year, the city funneled more than $1 billion, or approximately 10.5 percent of its 2017 budget, into four of its six pension funds, more than doubling the city’s contribution a decade ago. And the city officials hope that POBs would save future taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Chicago is hardly the only jurisdiction considering this idea, however. Omaha Public Schools—which was less than 60 percent funded last year—was seeking $300 million in POBs this April. And the state of Illinois was seriously considering a whopping $107 billion POB borrowing earlier this year, despite already shooting itself in the foot with bad POB deals in the past.

However, “there is no free lunch” in the public pension realm. Despite the pension funding boost, POBs do not make the issuer any healthier. Rather, they shift the financial risks away from within the pension fund to the municipal authority (city, state, school district, etc.) itself. In a sense, POBs trade “hidden” pension debt buried within pension accounting for formal, bonded debt. If not accompanied by systemic reform, this can leave pension funds exposed to the same types of long-term risks in the future that have produced the kinds of pension underfunding seen today in many plans by burying the problems with a dump truck of money. That, in turn, yields an environment of long-term budgetary uncertainty for government employers.

At an operational level, a POB is created when a municipal government issues a series of bonds, collects the revenue, and transfers that revenue to the pension fund(s) like any other contribution. The pension fund then invests it and manages those contributions as if they came from the government employer as an overpayment using dollars from a budget surplus.

From the perspective of the pension fund, it doesn’t matter where the dollars come from—POBs simply create a one-time pool of funds that can be used to increase the overall asset base of the pension system, and—on paper, at least—improving a plan’s funded ratio.

However, the source of the funds matters a great deal to the state or municipality who needs to cover the debt service on issued bonds and navigate a range of factors all of a sudden in play, including market conditions, credit ratings (which shape bond rates), and flexibility to raise taxes if budgetary hurdles arise.

In extreme cases when a state or municipality can’t possibly keep up with required annual pension contributions due to enormous claims they have on government finances, POB issuance might perhaps be justified as part of a larger pension reform effort designed to lower or eliminate long-term financial risks, similar to the approach taken by Houston last year. In that case, taking out a loan in the form of POBs can serve as a bridge to prevent any further degradation in pension solvency while “buying time” for the long-term reforms to work at de-risking the pension system.

But that is not what often happens. Instead, time and time again these bonds are used as a stand-alone tool by the governments failing to make good on their annual pension contributions and wanting to put a quick Band-Aid on growing pension debt.

Ironically, these often tend to be states and municipalities poorly equipped to shoulder the long-run risks packaged with POBs, exacerbating the problem. A 2014 study by the Boston College Center for Retirement Research (CRR) found that the top three POB issuers since 1985—when the city of Oakland, California, made history issuing the first POB—have been Illinois, New Jersey, and California, states with some of the worst-funded retirement systems in the nation.

One of the key risks that POBs pose comes from the implied pursuit of so-called “actuarial arbitrage.” This is when a government bets on the proceeds—which are invested by the struggling public pension plan(s) as part of its overall asset portfolio—to generate investment returns higher than the rate of debt service payments on the issued POBs. Such a bet is essentially a gamble with public money. With the “new normal” lower yield environment there is a considerable chance to generate a net loss and increase the budgetary burden in the long-run if pension investments underperform relative to the POB borrowing rate.

Additional long-run risks associated with POBs include:

- Moving liability risks away from public pension plans to states and municipalities;

- Undermines intergenerational equity, where future taxpayers are required to continuously foot the POB bills;

- Sharp increases in public debt because of POBs that can trigger credit rating downgrades, increasing future borrowing costs;

- Instead of somewhat flexible pension debt (amortization of which could theoretically be smoothed out), governments face a stream of inflexible annual debt payments;

- Provides no incentive to de-risk pension portfolio allocations, leading to continual chase for higher yields, thereby risking more volatile returns.

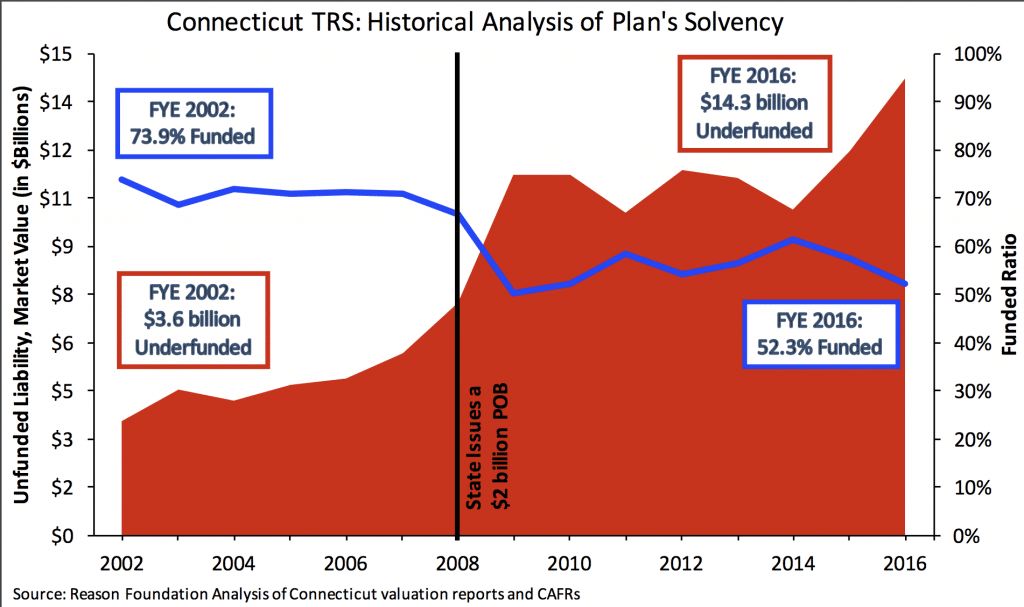

Examples abound of risky POB bets. “We achieved a favorable borrowing cost of 5.88 percent, which is well below the 8.5 percent assumed long-term return on assets of the Teachers’ Retirement Fund (TRS),” said former Connecticut Treasurer Denise L. Nappier back in 2008 when the state issued a $2 billion POB. Since then, however, the Connecticut TRS’s actual returns have averaged out to just 4.08 percent, far below the POB rate and the plan’s return assumption. The pension plan is now more than $14 billion in the red (market value).

In a similar vein, the aforementioned CRR study shows that as of 2009, POBs nationally had lost 2.6 percent in earnings for its issuers. That is not to say that reinvested funds can’t generate net positive results, given that most such bonds have yet to mature. However, there is no guarantee that the gamble will pay off in the long-run, as growing evidence suggests that much lower investment returns are likely over the next 10-15 years, relative to the past few decades.

And, with uncanny timing, this year’s “favorable” borrowing rate might turn out particularly ugly during the next market downturn – if the steadily flattening yield curve actually inverts.

Cities like New Orleans, Detroit and Stockton have already been negatively affected by bad POB deals during previous market downturns, the last two cities seeing POBs as one factor among those leading to Chapter 9 bankruptcy proceedings. And New Orleans—which in 2000 sold $171 million in bonds with a fluctuating coupon rate—ended up paying 11.2 percent instead of 10.7 percent interest, refinancing the debt a decade later.

There can be occasional silver linings. Connecticut’s state and local (e.g. town of Hamden) POB shows, for example, that POBs can be designed with covenants to bondholders that include a promise to pay 100 percent of actuarially determined employer pension contributions until the bond matures, a move that could nudge otherwise fiscally imprudent policymakers toward some degree of pension funding discipline.

Even that, however, should be taken with a grain of salt because annual actuarially determined pension contributions tend to be undercalculated whenever a public pension plan sets an over-optimistic investment return assumption, and in some cases continuously re-amortizes its unfunded liability. Thus, even a pension plan that receives every dollar of pension contributions as calculated by the plan actuaries may still fall short of fully funding its liabilities.

Still, even if one succeeds in garnishing positive net returns on a POB, the Government Finance Officers Association rightly points out that continuously failing to achieve the targeted rate of return alone would burden the issuer with both inflexible (i.e. almost impossible to renegotiate) POB debt service requirements, as well as rising unfunded pension liability payments—a “double whammy” from a fiscal perspective.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to public pension underfunding. And state and local governments often have to strike a delicate balance between short-term budgeting and long-run pension solvency. But, more often than not, POBs serve as a poor substitute to meaningful pension reforms and should be avoided when possible.