The Census Bureau has been tracking public pension systems for decades and provides useful information on funding trends every year. For example, the Census Bureau’s first survey, in 1941, found that state pension systems had collected $145 million in revenue and paid $58 million in benefits. Over the years, the bureau has expanded its overage to local pension systems and added information about pension plan membership and the composition of assets.

Relative to private data sources, such as the Center for Retirement Research’s Public Plans Database, the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of Public Pensions provides data on more systems but has far fewer attributes for any given system.

Last month, the Census Bureau added new data elements to its coverage. The latest data set includes total pension liabilities, net pension liabilities, and the discount rate applied to expected future benefits in order to compute liabilities. The new data file released on Oct. 6 has liability information for 870 pension systems nationally. While this is a small fraction—by count—of the more than 5,000 state and local pension systems the Census Bureau has identified, the sample includes most of larger public pension systems and thus covers most actuarial liabilities reported nationally.

The Census Bureau’s 2019 survey found that state and local pension plans were 73.6 percent funded on a dollar-weighted basis, meaning for every dollar of liabilities these systems reported, they had 73.6 cents in assets. Actuarially determined liabilities totaled $4.7 trillion while the assets to cover these promised benefits totaled just $3.5 trillion.

The Census Bureau also found that 76.1 percent of surveyed pension plans made actuarially determined employer contributions (ADEC) that equaled or exceeded amounts calculated by system actuaries. ADEC is the amount calculated each year by the plans’ actuaries to determine how much the employer needs to contribute to a pension fund’s pool of assets to maintain full funding. ADEC typically consists of the employer’s share of the normal costs plus any unfunded liability amortization payments needed to cover the existing debt.

The goal of pension plan managers is that these contributions accumulated over the years, together with the interest gained on them, are sufficient to pay for promised pension benefits. Failure to pay ADEC in full in any year results in the growth of unfunded liabilities and a decline of the funded ratio of the pension plan.

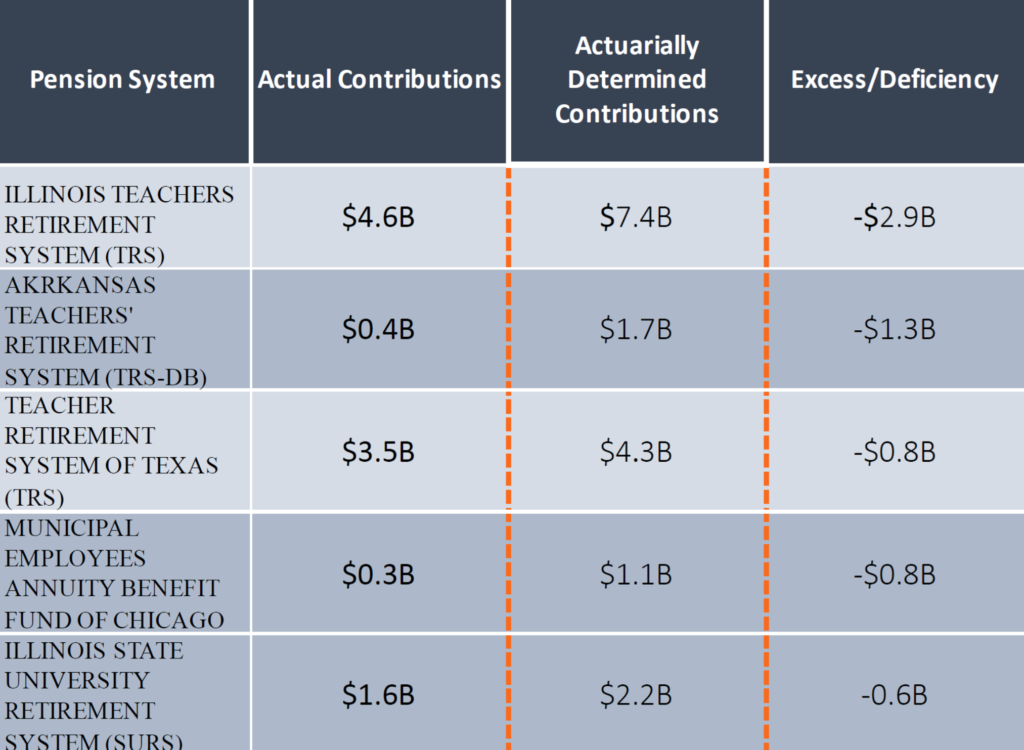

Underpayments by just five systems accounted for the entire nationwide gap between actuarially determined employer contributions and actual payments (across the other 865 systems, overpayments and underpayments roughly offset each other). Across the Census Bureau’s sample, total ADEC requirements were $149.3 billion in 2019, while actual contributions were $144.2 billion.

The five systems driving the gap were the Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois, Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago, State Universities Retirement System of Illinois, the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

According to a report by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), pension plans that fail to pay their ADEC in full increase unfunded liabilities, and thus increase the long-term costs of funding their pension plans.

Any pension funding shortfall represents a portion of assets that a system will not be able to use for gains through investment returns, a key to the success of a retirement plan. If a plan is losing out on investments, this deficit must be made up with additional contributions down the road.

To keep a public pension plan’s funding on track, the ADEC needs to be paid in full. Pension plans fall into one of two categories when it comes time to make contributions—those that tie their annual contributions to the ADEC, and those with a statutory contribution requirement. The latter has a predetermined amount of employer contributions each year. While the amount could coincide or be above the ADEC, problems will arise when it is below ADEC and no supplemental contribution is made to close the difference. Without those supplemental contributions to make up the difference, the plan will not put enough money into the pension plan, therefore increasing unfunded liabilities.

Other than statutorily determined contributions, another reason for not paying ADEC in full could be overall budgetary constraints. The long-term nature of pension liabilities could tempt policymakers to underpay the actuarially determined employer contributions in times of market fluctuations and extraordinary circumstances in order to divert funds to more immediate priorities.

To guarantee the long-term solvency of public pensions, plan stakeholders need to prioritize adequate payments into the system. Failing to pay enough can derail the plan from accumulating enough funds to pay out pension checks for future retirees. The latest results from the Census Bureau demonstrate some major shortcomings in funding policy for public pensions and should be addressed by states and localities quickly.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.