The Alaska state legislature is currently considering reintroducing a pension benefit for public safety workers in hopes of increasing workforce retention among first responders in the state. Unfortunately, rather than achieve its stated aims, the proposed policy would introduce major financial risk at a time of market volatility and commit Alaska to a near-certain future of growing unfunded liabilities—debt—because the state would be unable to pay the full costs associated with promising guaranteed lifetime income in retirement to generations of future first responders.

House Bill 55 (HB 55)—currently under committee consideration in the State Senate—would open a new tier in the pension plan that was closed to new entrants back in 2006. The legislation would make minor adjustments to employee contributions and retirement eligibility relative to the pre-2006 public pension system. While a defined benefit pension plan can be structured in ways to limit and share risk, HB 55 does too little to prevent growing unfunded pension liabilities, as discussed in the following sections.

In 2005, facing a massive drop in funding and growing annual costs, Alaska closed the state’s pension plan, the Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS). Since that time, new workers were placed in the state’s Defined Contribution Retirement Plan (DCR), which has generally served as an effective retirement benefit for members (though potential improvements to the DCR design will be the subject of a future article). Alaska’s current defined contribution plan has the advantage of providing a competitive retirement benefit to public workers with a predictable and stable cost to state employers.

Opening a new tier in the previously closed PERS defined benefit pension system, as proposed in HB 55, would move the state away from its current risk-free retirement design for new public safety hires. Today, employers bear no further liability once their DCR contributions are made to the employee’s retirement account and this proposal would expose the state to the same types of unfunded liabilities that prompted closing the pension 15 years ago. Notably, the state still has $4.6 billion in unfunded PERS liabilities today despite having no flow of new plan entrants for 15 years.

House Bill 55 does include a few tweaks to the proposed new PERS tier (relative to the pre-2006 pension) that proponents suggest are intended to lower the financial risk to the state. Below is a list of these adjustments, as well as comments on these proposed changes based on the Pension Integrity Project’s experience and analysis:

- Setting a minimum retirement age of 55 if members have 20 years of service.

- The legacy PERS pension had a 20-years-and-out feature, which meant that a firefighter hired at 21 could retire at 41 with his/her fully accrued retirement.

- “55-and-20” would improve upon that by setting a minimum retirement age, but at the same time, age 55 is also a fairly low bar as a minimum age.

- Raising employee contribution rates from 7.5% in the legacy pension to a min 8% and max 12%.

- While these employee rates are higher, they still fail to share the risk of unexpected costs of the plan with employers.

- The employee rate cap also means all future underperformance beyond that limited contribution increase is placed on the backs of state and local employers and their budgets.

- Because the plan’s assumptions and funding design are flawed, a long-term risk of insufficient contributions still exists.

- Suspending the post-pension retirement adjustment if the plan falls below 90% funded, and completely removing the annual Alaska cost-of0living adjustment.

- These are both prudent cost-control measures relative to the previous policies.

To date, HB 55 has faced minimal actuarial scrutiny and there is no publicly available long-term actuarial forecasting or stress testing to justify such a financially profound policy decision. Public pension systems operate over generations, but state legislators have only been presented with minimal five-year cost projections based on an assumption that the proposed pension tier would do the impossible: get 100% of its assumptions 100% right, 100% of the time.

While the five-year cost analysis—performed by the PERS consulting actuary, Buck Global—is limited in its scope and rigor, it does raise some major concerns that should alarm state policymakers. The report states, “Adverse plan experience (due to poor asset returns and/or unexpected growth in liabilities) or changes to more conservative assumptions will increase the plan’s unfunded liabilities, which results in higher Additional State Contributions.”

It also notes that:

“[t]he impact of HB 55 on projected Additional State Contributions depends on how large the unfunded liabilities become. If the Actuarially Determined Contribution rate for HB 55 members’ pension and healthcare benefits exceeds 9%, then HB 55 will lead to larger increases in Additional State Contributions compared to what would have happened without HB 55…By shifting active P/F members (and all future P/F hires) from DCR to DB, the State will be taking on greater risk of higher contributions in future years.” (emphasis ours)

Given that the limited actuarial analysis that exists warns that the proposed reintroduction of a pension plan would also be committing Alaska to unpredictable long-term costs in the future, it is crucial for state decision-makers to first consider the implications of HB 55 over multiple decades, not just a few years.

Examining the Actuarial Impacts of the Proposed HB 55 Pension Tier

Recognizing the need for a long-term perspective on funding and costs, the Pension Integrity Project has prepared preliminary modeling of the proposed new HB 55 tier; it is important to note that these results do not include potential impacts on the legacy PERS tier and its current $4.6 billion in unfunded liabilities.

The results of our analysis indicate that, despite efforts to manage risk relative to the pre-2006 pension system available to first responders, HB 55 would still expose the state to obligations that are likely to cost much more than initial estimates indicate.

Pension Integrity Project modeling of House Bill 55 finds that the new pension plan would require a total of $743 million in employer contributions over the next 30 years, but this assumes that the fund:

- Meets its current actuarial assumption (7.38%) each and every year—which is virtually impossible—and;

- Never faces any unfunded liabilities along the way.

A complete evaluation of the potential costs of this bill needs to also include scenarios in which investment returns do not match the pension plan’s expectations. What is more, it is important for state policymakers to understand how the proposed plan would respond to market stresses.

With that in mind, our analysis below applies a scenario in which two economic recessions occur over the next 30 years (one in 2023 and another in 2038), and investment returns for other years come in at 6%— in line with the average 10-to-15 year forecasts in a survey of 39 financial experts.

The stress scenario applied to the new pension proposed in HB 55 would result in unfunded liabilities that would require higher contributions from state employers. Instead of the $743 million paid in employer contributions over the observed 30-year window if all current actuarial and demographic assumptions are met, Alaska would be responsible for paying $887 million instead due to the need to service growing unfunded liabilities.

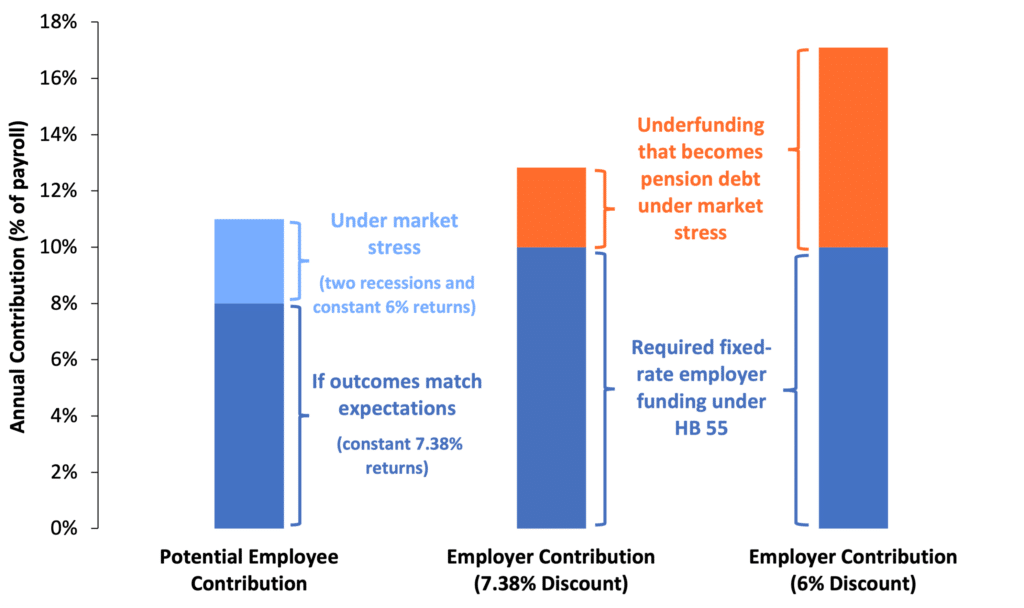

Figure 1 breaks down the ranges of annual contributions both employees and employers could expect under the proposed plan. As explained above, HB 55 includes the potential for increases in employee contributions, depending on need. Predictably, the market stress scenario used in this analysis would bring rates up for employees. Market stress would also require more of the state. While employer contributions are set at 10% in the proposed plan, these rates would also need to go up to meet the demands of unfunded pension liabilities.

Failure to answer the call for higher employer contributions in this scenario would result in the accrual of expensive public pension debt. Alaska does not have a set policy to enforce these necessary contribution increases and the proposed reform does not establish one. With that in mind, we are left to assume that contribution rates would remain static, thus passing these unfunded obligations—debt—onto future generations and weighing on state and local government budgets perpetually.

Figure 1: Market Stress on Employee and Employer Contributions Under Proposed HB 55 Tier

A great deal of the risk the state would be taking on is also hidden with discounting policy. The proposed plan would discount liabilities at PERS’ current 7.38% rate. Considering most state pension plans across the country are adjusting their investment return rate expectations down to, or below, 7%, this would place the new Alaskan defined benefit discount rate on the higher end of investment expectations, meaning a good portion of the state’s potential risks and costs could be hidden.

Adjusting the discount rate of the plan down to 6% reveals that a stress scenario could result in actuarially required contributions rising more than 7% over the currently reported and expected rate, totaling 17% of payroll annually within 20 years.

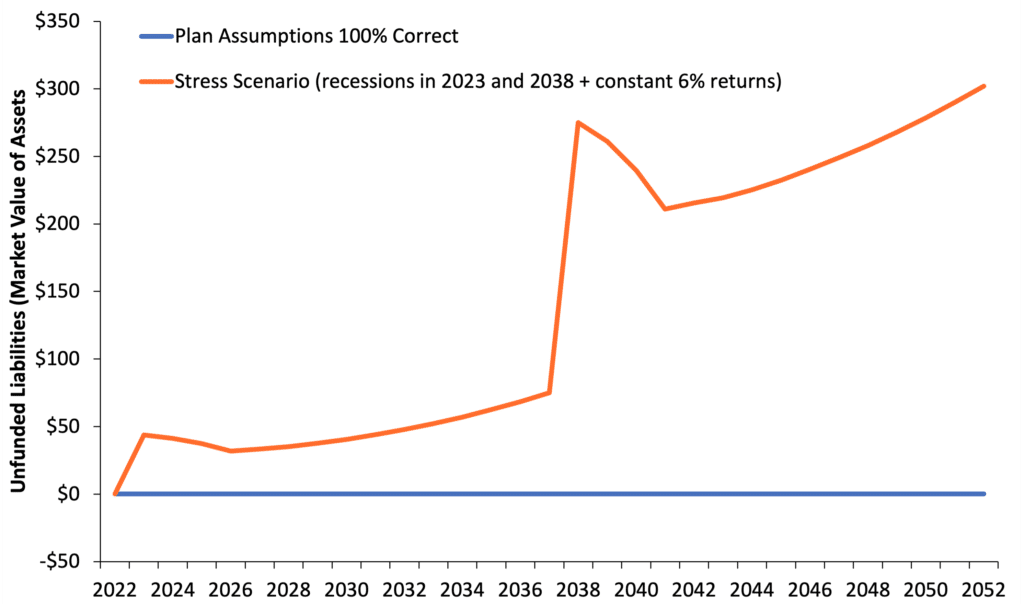

The stress scenario also reveals the risks of pension debt that would still exist under the proposed reform. While the pension plan would accrue no unfunded pension liabilities under a scenario in which plan assumptions are met, recessions and overall returns that fall below the plan’s overly optimistic assumptions would create significant funding shortfalls.

Applying the two-recession stress scenario shows that the new plan could go from no unfunded obligations to having as much as $302 million in pension debt by the end of the modeled 30-year window (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Unfunded Liability Forecast of New Pension Plan Proposed in HB 55

This issue would not be exclusive to long-term perspectives, either. The proposed HB 55 pension tier would be immediately susceptible to accumulating significant unfunded liabilities due to the decision to allow current DCR plan members to transfer their defined contribution plan assets into the new pension as if they had been in the new pension the entire time. This practice would essentially use these funds to have existing members buy into guaranteed pension benefits in the middle of their careers. This policy would also represent a large and immediate new exposure to market risks for Alaska.

Proponents of the bill argue that this is a cost-neutral way to allow members to switch a defined benefit pension midstream, but this again is relying on a very improbable 7.38% rate of return. If market outcomes end up diverging from the plan’s very optimistic assumption, the funds transferred will end up being inadequate to provide the promised pension benefits, with the responsibility for the shortfall once again falling to the state.

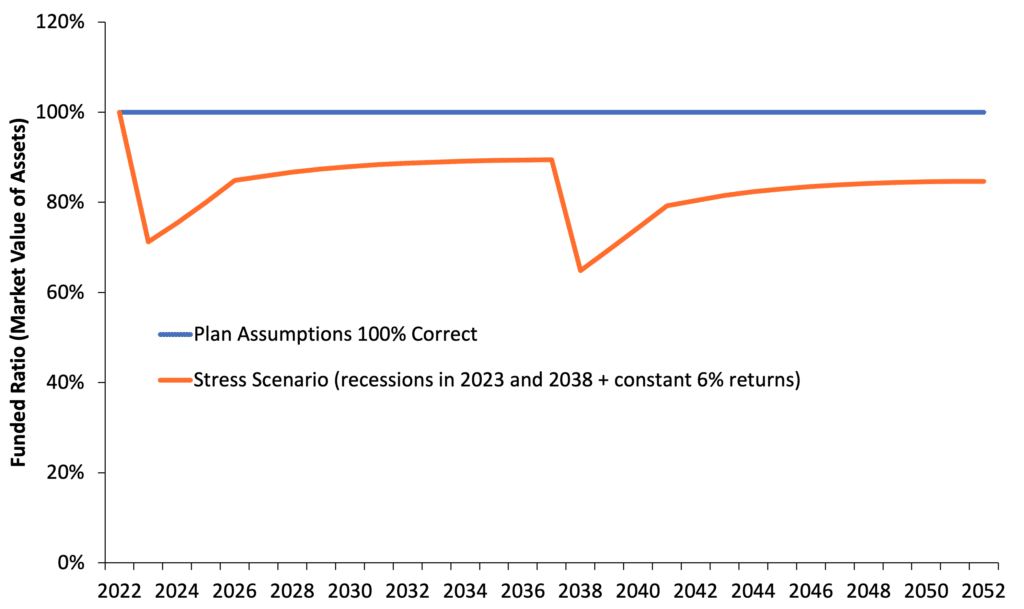

The immediate threat of this problem surfaces in our actuarial analysis. Modeling of the new pension shows that a single recession year in 2023 could immediately generate unfunded liabilities and go from fully funded to 71% funded after just one bad year of losses.

This type of scenario should be very familiar to Alaska legislators. The state’s funding woes that precipitated the 2005 pension reform began after 2001 losses, where they saw the pension fund go from $50 million overfunded to $1.5 billion underfunded in just one year, dropping from the pension system being 100% funded to just 75% funded. According to this analysis of HB 55, those same risks that existed in PERS before its closure would still largely exist in the newly proposed plan.

Figure 3: Funding Forecast of New Pension Plan Proposed in HB 55

Had a long-term actuarial forecast been requested to accompany this legislation, and had there been a review of the financial outcomes of HB 55 in underperforming investment scenarios, Alaska policymakers would clearly see that the proposed HB 55 pension tier for first responders resembles nothing like the supposed “low-risk” or “risk-free” pension described by bill proponents.

By allowing the transfer of funds held in members’ defined contribution accounts immediately into the new pension system at an unreasonably high discount rate, the “new” pension tier would, within the first few months of existence, become a somewhat mature pension plan—with all the attendant financial risks of traditional defined benefit pension systems.

The national trend since the Great Recession of 2007-2009 has been for states to adopt greater risk controls in their traditional public pension systems and move towards a variety of plan design options with the goal of avoiding re-exposing state and local budgets to the risks of worsening unfunded pension liabilities over the long-term.

Unfortunately, House Bill 55 does not resemble those types of prudent retirement reforms. Considering the serious levels of risk that Alaska could be taking on with HB 55, policymakers should seriously consider going back to the drawing board on more effective methods of managing and sharing risk. Once risk policies that are more in line with modern reforms are agreed upon, a rigorous long-term actuarial analysis should be performed on those proposals to ensure lawmakers aren’t entering into the risky retirement commitments that created debt and fiscal challenges for Alaska in the past.