California Proposition 20: Criminal Sentencing, Parole, and DNA Collection Initiative

Summary

California’s Proposition 20 would make significant changes to criminal justice reform laws passed by the legislature and Propositions 47 (2014) and 57 (2016), which were approved by voters. It would roll back many changes to the classification of crimes, creating more felonies and violent crimes. Proposition 20 would also create two new crimes—serial and organized theft as well as reinstate DNA collection for less serious crimes, make fewer people eligible for parole, and change what parole boards must consider when making parole decisions.

Fiscal Impact

The Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that Prop. 20 would lead to an increase in state and local correctional costs likely in the tens of millions of dollars annually due to an increased number of incarcerated Californians. In addition, there would be court-related costs of more than several million dollars annually, as well as increased law enforcement costs—not likely to be more than a few million dollars annually—related to collecting and processing DNA samples.

Proponents’ Argument For

Proponents of Prop. 20 argue that the changes from Proposition 57 (2016) allowed more parole for “nonviolent” crimes and ignored that California has narrow definitions of “violent.” With respect to crimes, “violent” excludes crimes such as sex trafficking of children, rape of an unconscious person, battery on a police officer or firefighter, and felony domestic violence. Supporters say that this means more people who were convicted of crimes that thee average person thinks are violent are getting out early on parole. At the same time, Prop. 20 would require parole boards to consider an inmate’s entire criminal history, not just current offenses and circumstances.

Proposition 47’s (2014) shift of some crimes from felonies to misdemeanors has meant law enforcement can collect DNA samples from fewer suspects. Studies show DNA collected from crime suspects helps solve other violent crimes. Since Prop. 47, cold-case hits have fallen by around 2,000, about one-quarter of which are unsolved violent crimes. Prop. 20 would fix this by allowing DNA testing for many crimes that were reduced to misdemeanors, proponents say.

Supporters of Proposition 20 say California has too many career criminals. Prop. 20 would close a critical loophole that allows thieves who repeatedly steal property just below the felony threshold to only face misdemeanor charges—now a third offense of stealing items worth over $250 would be a felony.

Opponents’ Argument Against

Opponents of Prop. 20 argue that the changes would cost tens of millions of dollars every year on a failed approach to crime that California and other states have already learned does not work. Locking more people up for crimes and for longer times in prison didn’t work in the past, and won’t work now, but will demand wasting more money on prisons. Opponents of Prop. 20 say this money could come from cuts to pre-release rehabilitation programs, mental health programs proven to reduce repeat crime, schools, healthcare, housing, homelessness programs, public safety, and support for victims.

Prop. 20 means petty theft, like stealing a bike, could lock up more teenagers and people of color for years for low-level, non-violent crimes. At a time when Californians are demanding changes to the criminal justice system and after a decade of voting to end wasteful prison spending and develop alternatives to arresting and imprisoning people, Prop. 20 is a huge step backward. The best way to reduce crime is to rehabilitate people before they are released from prison, not lock them up longer and more often.

California’s crime rates are at historical lows thanks to the criminal justice reforms approved by voters over the past decade. Now is not the time to allow Prop. 20 to reverse that progress, opponents argue.

Discussion

In the 1990s, California adopted strenuous ‘tough on crime’ policies like the 1994’s ‘three strikes’ law. These policies led to a massive increase in incarceration and the state’s prison population exploded. During the 1990s the state of California opened 12 new prisons. Despite that massive growth, the system still became extraordinarily overcrowded, leading to a string of lawsuits and court rulings that culminated in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling upholding a judicial order to reduce the state’s prison population.

In response, the legislature passed Assembly Bill 109 in 2011 which realigned the state correctional system and shifted the imprisonment of non-serious, non-violent, and non-sexual offenders, as defined in state law, from state prisons to local jails. Within a few years, voters also passed Prop. 47 (2014) and Prop. 57 (2016) further changing state law to refocus the criminal justice system on alternatives to both incarceration and longer sentences to punish crime. California has since been a national leader in reducing incarceration rates. However, law enforcement groups have criticized the reforms for being lax on criminals and for raising crime rates.

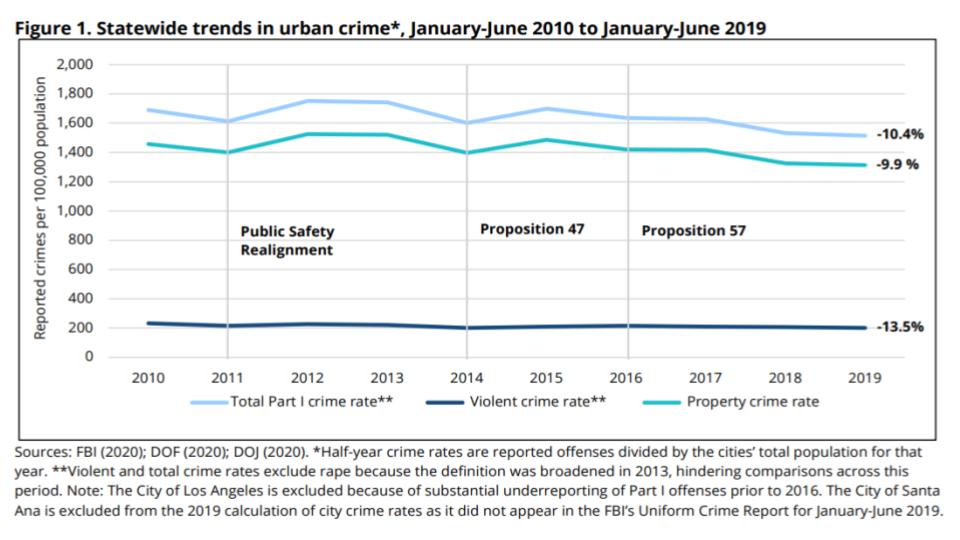

Crime rates in California fell during the 1990s and the state’s tough on crime era, but they also fell in the rest of the country. And more importantly, as Figure 1 shows, crime rates continued to fall in the last decade as criminal justice reforms were enacted. Unfortunately, most people think crime rates have been rising.

Source: Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, 2019

Where crime in California did increase in recent years, some of it was due to the way crimes were counted, but a noticeable increase in larceny-theft could be linked to Prop. 47, with three-quarters of the increase due to motor vehicle thefts. Even opponents of Prop 20. agree that fixing that error in Prop. 47 is crucial, but the other changes Prop. 20 makes would be harmful to criminal justice reforms the state has made.

Between 2011 and 2015, recidivism and felony re-conviction rates in California fell by 27 percent across 12 counties that represent nearly two-thirds of the state population. The re-conviction rate for all crimes fell by 15 percent.

Proposition 20 therefore would seem to be rolling back successful reforms based on arguments about increases in crime that are not true. A study of the effects of Prop. 20 concludes it would cost hundreds of millions of dollars each year, not just tens of millions, leading to cuts in crucial services and alternatives to prison, which would return California to overcrowded prisons and expensive lawsuits, and set back the state’s success at reducing crime and recidivism.

The state Department of Finance estimated that Proposition 47’s reforms resulted in savings of $228 million from 2015 to 2019 and predicted $122.5 million in savings in 2020. That money is invested in programs to reduce crime such as mental health, substance abuse and diversion programs for criminal offenders, school programs for at-risk kids, and trauma recovery services for victims.

A crucial matter in judging if Prop. 20 makes sense is understanding whether more imprisonment and longer sentences actually reduce crime, improve public safety, and further justice. California’s experience with criminal justice reforms casts doubt on that idea, but there is much more extensive evidence.

A massive research project by the National Academy of Sciences has shown that the increase in prison populations nationwide since 1980 is driven by increases in sentences more than increases in crime. Put another way, it shows that decades of the rising use of imprisonment and longer sentences to punish crime did not much affect crime rates. Similar research has found that the return to prison of repeat offenders was mostly due to technical violations and failures in post-prison community supervision rather than changes in sentences.

Some research has found that longer sentences for repeat offenders do reduce crime, specifically by deterring crimes on which the sentences were lengthened, but also finds that the effects are small and the costs may exceed the benefits.

Most research on how longer sentences affect crime conclude they “have become counterproductive for promoting public safety” because:

- long-term sentences produce diminishing returns for public safety as individuals “age out” of the high-crime years;

- such sentences are particularly ineffective for drug crimes, as drug sellers are easily replaced in the community;

- increasingly punitive sentences add little to the deterrent effect of the criminal justice system; and

- mass incarceration diverts resources from program and policy initiatives that hold the potential for a greater impact on public safety.

Indeed a large body of research and basic guidelines from the National Institute of Justice shows that crime is deterred much more by the certainty of punishment than by the severity of punishment. The National Institute of Justice guidelines points out that longer sentences may actually increase crime, while better policing deters crime through both increased certainty of punishment and sentinel effects: “A criminal’s behavior is more likely to be influenced by seeing a police officer with handcuffs and radio than by a new law increasing penalties.”

Several periods of reduced sentences for federal crimes have shown they did not lead to more repeat offenses. A large panel of criminal justice researchers looking at the overall evidence argue that, while more time in prison can mean less time for an individual to do crime and thus reduce their recidivism and in aggregate might reduce crime, this effect is not large overall and has been declining over time, and increasing sentences has almost no deterrent effect on criminals. What the evidence shows is that:

Increased incarceration at today’s levels has a negligible crime control benefit: Incarceration has been declining in effectiveness as a crime control tactic since before 1980. Since 2000, the effect on the crime rate of increasing incarceration, in other words, adding individuals to the prison population, has been essentially zero. Increased incarceration accounted for approximately 6 percent of the reduction in property crime in the 1990s (this could vary statistically from 0 to 12 percent), and accounted for less than 1 percent of the decline in property crime this century. Increased incarceration has had little effect on the drop in violent crime in the past 24 years. In fact, large states such as California, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Texas have all reduced their prison populations while crime has continued to fall.

Prop. 20 also reclassifies violent crimes. Punishments in California law are established for each crime based on many factors, including violence. Prop. 57 (2016) introduced the technical classification of “violent” crimes into the state constitution to indicate that certain crimes are not eligible for parole. To say a vast list of clearly violent crimes are not considered violent by state law is misleading because courts always take that into account in adjudicating and sentencing. Prop. 57 created the current definitions so that that parole could be used for more felony offenders who show progress on rehabilitation. Prop. 20 would dramatically curtail this.

Finally, Prop. 20 would reinstate DNA collection for some offenses. In 2004, voters approved Prop. 69, requiring the collection of DNA from anyone arrested for a felony. The idea is that this DNA information goes into law enforcement databases and can be used to solve crimes where DNA evidence is found. And that does happen. When Prop 47 reclassified some offenses from felonies to misdemeanors, DNA could no longer be collected from those arrested for such offenses. Prop. 20 would reinstate DNA collection for those offenses.

The problem is that collecting DNA from those convicted of a crime is one thing, while collecting it from those merely suspected and arrested is another. Our criminal justice system is based on everyone being innocent until proven guilty. Taking DNA from someone who has not been convicted of a crime puts them into a law enforcement database and treats them like a criminal when they have not been convicted of a crime.