With the rise of the affordable automobile in the 20th century, Americans overwhelmingly switched to cars, which offered private, door-to-door service. By the 1960s, privately-owned streetcars and bus lines, operating under municipal franchises, were almost all replaced by public sector buses receiving government subsidies. Unfortunately, today, government-operated mass transit has low overall ridership and is highly subsidized, with each ride costing taxpayers $5 in operational and capital expenses.

Over the course of a decade, the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 provided more than $3 billion in federal subsidies to transit capital projects. Despite substantial taxpayer money being directed toward mass transit, ridership continued to decline. By the 1980s and 1990s, local governments felt the pinch of mass transit’s financial burden, even with all of the federal and state subsidies.

As a result, the United States and Western Europe saw an initial wave of transit contracting. A 1998 survey of 259 American transit agencies found that 20.4 percent of transit vehicles, 16.5 percent of vehicle revenue-miles, and 9.4 percent of operating expenses were delivered through purchased services. Contracting for demand-response services far outpaced contracting for fixed-route bus services, as 74.7 percent of demand-response vehicles were operated under purchased services compared to only 6.7 percent for buses. The discrepancy in contracting prevalence between the two modes is primarily due to the higher labor costs associated with demand-response systems.

For fixed-route buses, the initial wave of contracting brought direct savings ranging from 30 percent to 60 percent, and the competitive market brought down public sector costs as well.

For example, prior to adopting a competitive contracting program in 1979, San Diego’s mass transit costs per mile increased at a similar rate to U.S. transit overall. After the conversion, costs per mile increased at half that rate through 1990. This initial wave of transit contracting also saw service quality maintained or improved in cities such as Denver.

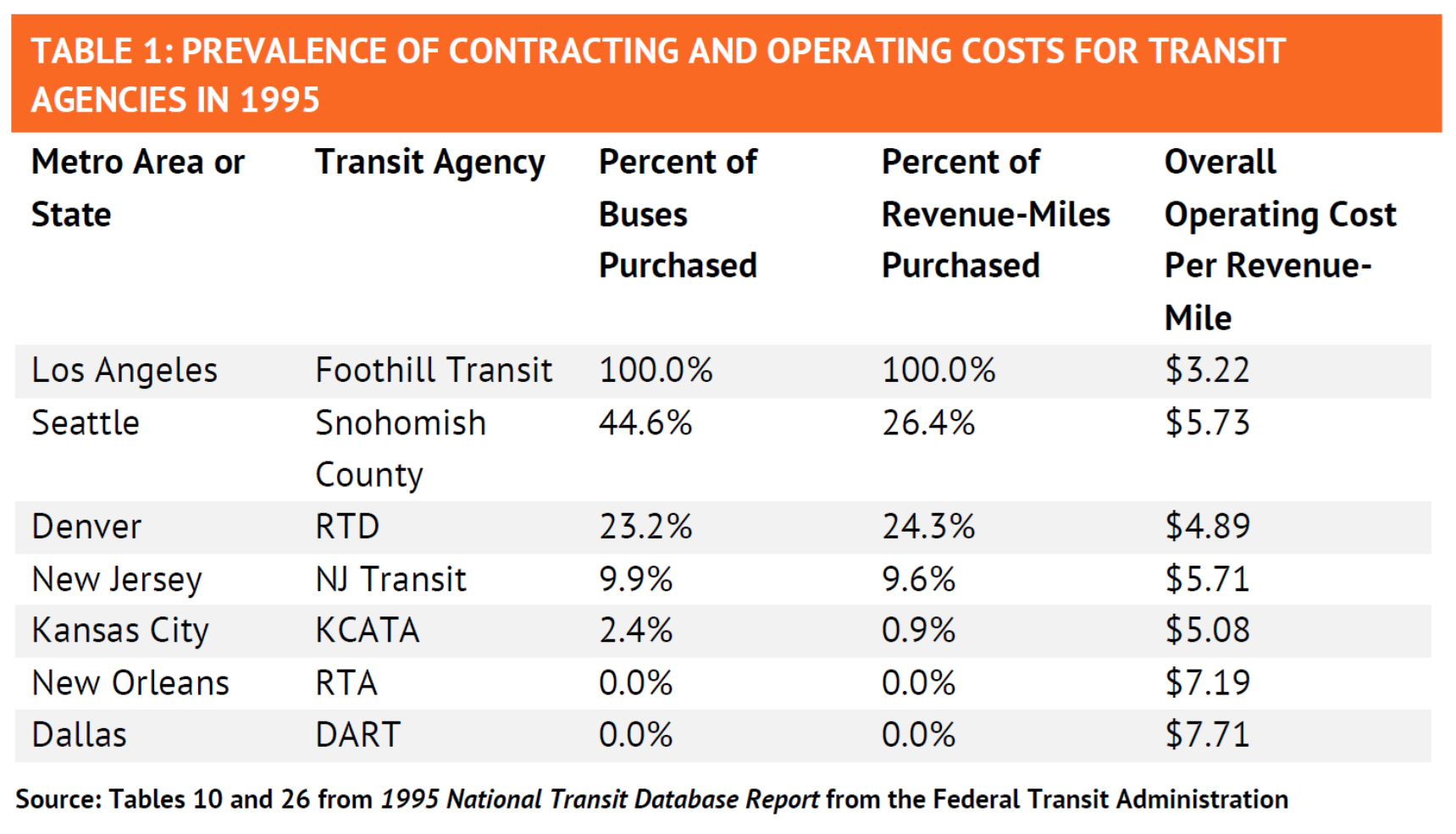

Table 1 provides an overview of the prevalence of fixed-route bus contracting and overall bus operating costs at select transit agencies in 1995.

Like any newly adopted practice, mass transit contracting’s best practices were not entirely known by the 1990s. For example, the conservative government that enacted transit contracting in the United Kingdom switched the contract structure, allowing the private operator to retain all fare revenue as the sole source of funding. However, service quality declined as providers looked to cut costs and focus only on transit-dependent riders. Reforms in 1997 created service quality standards and incentive bonuses based on providers exceeding requirements. Today, London continues to contract out its bus service.

In the United States, however, transit contracting, particularly for fixed-route bus services, stagnated among principal cities and their transit agencies. In 1992, the Kansas City area contracted 10 percent to 14 percent of its buses but contracted none in 2018.

While Los Angeles’ principal transit agency contracts only 7.6 percent of its buses, the total contracting rate across the metropolitan area is 30 percent in 2018, up from under 15 percent in 1992.

A 2013 Government Accountability Office survey of 463 transit agencies found that 42.3 percent of agencies with fixed-route buses contracted at least some of their service, with the remaining 57.7 percent operating all bus routes directly.

As in 1998, a greater percentage of transit agencies contracted their demand response service than their fixed-bus routes. Fifty-seven percent of Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, paratransit systems utilized purchased services, as did 62.4 percent of non-ADA demand response systems.

The current scope of the private intracity bus industry is a testament to the effectiveness of contracting, as the metropolitan areas of Las Vegas, Austin, Phoenix, and Reno, among others, contract out all bus services successfully.

While private-sector transit and the deregulation of micro-mobility and ridesharing can decrease demand for traditional transit services, contracting transit offers governments a more widely applicable method to decrease transit costs and increase service quality.

Direct savings, which can be over 30 percent, are only one of the benefits, as savings will ripple throughout a city’s and state’s transit sectors.

San Antonio, for example, doesn’t contract buses due to its current low cost of $7.24 per revenue mile. It does, however, contract all of its vanpools and half of its paratransit service, employing contracting’s cost savings where needed. Other cities in Texas, a state comfortable with contracting, sees transit costs well below the largest 50 transit agencies’ cost of $14.32 per revenue mile. For example, Austin’s and Dallas’ costs are $9.89 and $9.40 per revenue mile, respectively.

The private sector typically brings a business-like approach that is more willing to adopt new technology and work hard to establish positive experiences for its passengers. European cities such as Stockholm have allowed private companies to innovate by letting them choose exact routes within a given service area. In the US, private contractors also helped New Orleans begin to address transit pension challenges and restore much of the service lost to Hurricane Katrina.

Barriers exist in contracting transit but they can be overcome. Unions, fearing contracting will decrease labor prices and their political influence, sometimes prevent contracting through collective bargaining agreements. Policymakers should reach out and work with unions to explain why contracting, financial stability, and improved transit service quality constitutes a mutually beneficial proposition. Private operators can follow collective bargaining agreements, pay workers more, and still cut costs.

When unions do not cooperate, cities and counties should leave established centralized transit agencies and provide transit outside of a legacy union’s jurisdiction. Even in states that require private transit workers to be part of the public sector union, contracting has been found to bring down costs and improve service quality.

Most other barriers to contracting transit are largely perceived. Mass transit agencies can maintain and expand control of service with a well-crafted contract. Savings, service quality improvements, and preparing for the future of on-demand private transit are ample impetus to pursue contracting. Federal regulations, such as Section 13(c) of the Federal Transit Act, have never actually prevented a transit agency from contracting. Policymakers and transit agencies should work to communicate the effective and long-term benefits of transit contracting within the context of their metropolitan area.

Setting up a contract begins with determining if the transit agency can provide service with the best overall value. Often it cannot. The procurement process, from informal market sounding to financial close, must set clear expectations that encourage participation and, thus, competition. The final proposal should be chosen from a predetermined rubric that calculates the best overall value, factoring in service quality, scope, and cost.

The contract must be detailed and encompass all areas including duration, bonding, service scope, maintenance, insurance, and pricing. Pricing is the most important component of the contract, as it must encourage competition and mitigate taxpayer risk. Fixed-priced contracts work well when coupled with financial penalties and discretionary incentives set at predetermined levels to promote service quality. Net-price pay fosters a direct relationship between riders and the private entity through the farebox, fostering service quality; to attract bidders to a net-pricing system, a pass-through arrangement can be used to address unpredictably escalating costs such as for fuel.

Transit contracting should always follow three principles: guaranteeing public control, promoting competition, and ensuring transparency.

Public control allows transit to serve its desired function, which is best delivered by private operators. Those operators are, in turn, more cost-effective. A transparent process is one that encourages competition, has clear expectations, and establishes trust, decreasing costs further and promoting service quality.