Despite a strong economy, the federal deficit grew sharply in the fiscal year 2018 and it is expected to reach $1 trillion in 2019. The headline national debt numbers — over $21 trillion, of which nearly $16 trillion is publicly held — drastically understate the enormity of federal obligations in accrual accounting terms.

Although this red ink has yet to trigger a crisis, complacency is unjustified. As we have seen this year in Turkey and Argentina, excessive debt leaves a nation vulnerable to devaluation, inflation, financial instability, political chaos, and even sovereign default and hyperinflation. The fact that US debt is repayable in US dollars is no guarantee of repayment: a Bank of Canada report identifies 27 local currency sovereign defaults since 1960. (Even the US has previously defaulted on dollar-denominated debt under some circumstances.)

Because Treasury securities are so widely held, a US sovereign default could trigger a global financial crisis far worse than the meltdown we experienced in 2008. The relative strength of the US economy protected the dollar in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. But it cannot be assumed that that pattern will continue.

Our precarious fiscal situation is the result of budget-busting actions taken by both Democrats and Republicans, as well as the failure of both political parties to implement serious remediation measures. Because Republicans more often pay lip service to the deficit issue, their failure is a particular concern, and their economic rhetoric is rooted in misconceptions that, while politically convenient in the near-term, are doing great damage to the nation’s long-term financial health.

A Look at the Numbers

Each year the US government publishes audited financial statements based on federal accounting standards that use accrual accounting principles. Under accrual accounting, new obligations are recognized — i.e., included in the financial statements — when they are incurred. This is conceptually more accurate than budgetary accounting, which only considers cash inflows and outflows, and thereby misses long-term obligations, such as pensions.

As federal employees work, they accrue pension benefits to be paid during retirement. Actuaries — using assumptions about longevity, payroll growth, inflation, etc.— can make reasonable estimates of these future benefits and then report their discounted value in current dollars. The present value of these retirement benefits, about $8 trillion, is excluded from national debt statistics but included on the federal balance sheet as liabilities.

While Treasury does not include unfunded Social Security, Medicare and other social insurance obligations on the federal balance sheet, these amounts are reported in a supporting schedule, and can thus be easily added to reported liabilities.

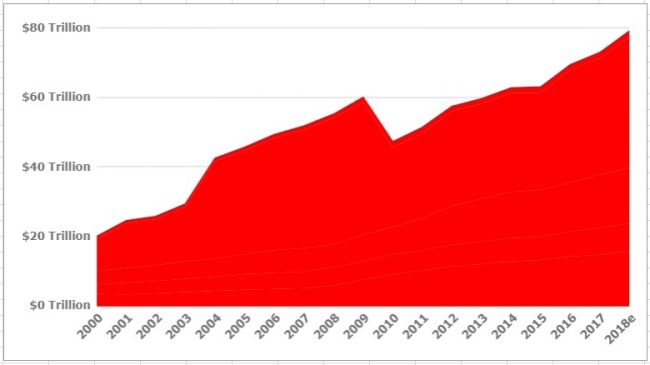

Chart 1 below shows federal debt liabilities reported on federal financial statements for fiscal years 2000 through 2017 with social insurance obligations added. Amounts for 2018, which will be published early next year, are estimated by the authors. Debt held by the public has increased from $3.4 trillion to $15.7 trillion since 2000. But this is only part of the story. Total obligations grew from $20.0 trillion to $79.2 trillion.

Source: Federal Financial Statements, Authors’ Calculations

Given the significant inflation and substantial economic growth since 2000, it is also useful to look at the growth of federal debts relative to nominal GDP. Debt/GDP ratios are provided in Chart 2. Since the beginning of the century, debt held by the public increased from 33 percent to 77 percent of GDP while total obligations grew from 195 percent to 388 percent of GDP.

Source: Federal Financial Statements, National Income Accounts, Authors’ Calculations

Trump Era Legislation

Despite Republican control of the House, Senate and executive branch since January 2017, the flow of federal red ink has increased. Two key measures that widened deficits were the December 2017 tax reform bill and the March 2018 omnibus spending bill. (The “minibus” spending bill passed in late September 2018 will add further debt.)

On paper tax reform is expected to add at least one trillion dollars to deficits over the next ten years. Further, Congress repeated the Bush-era approach of allowing personal income tax cuts to expire within the CBO budget measurement window as a way of limiting the reporting deficit impact. As we saw in 2010 and 2012, Congress is averse to allowing tax rates to rise for lower- and middle-income taxpayers. So, it seems likely that the new lower brackets will be extended beyond their scheduled expiration in 2025, with the effect of adding up to $140 billion annually to budget deficits in subsequent years. Because CBO makes projections according to current law, it ignores the possibility of tax-cut extensions, likely underestimating long-term deficits.

Congress followed up with an FY 2018 omnibus spending bill that sharply increased discretionary expenditures and essentially killed the sequestration process that had been restraining defense and non-defense appropriations. Passed almost halfway through the fiscal year, the omnibus was hardly a case of sober, deliberate budgeting: most members had little time to comb through the bill’s 2,200 pages before it was put to votes in the House and Senate.

Further, Congress and the Trump administration have done nothing to reform entitlements, which are inexorably growing, regardless of tax revenues. With Baby Boomers retiring, Social Security and Medicare caseloads are swelling rapidly and we face another decade during which the number of annual retirements will exceed the number of deaths.

With the youngest boomers entering their mid-50s, it is now hard to see how any entitlement reform can kick in before the dependency ratio (i.e., the ratio between the number of beneficiaries and social insurance taxpayers) peaks in the 2030s since previous reforms (both enacted and proposed) have required long phase-in periods to be politically palatable.

Misleading Ideas About Tax Cuts, Military Spending, and Deficits

Republican Congressional leadership is doing serious damage to the nation’s fiscal health in promoting two questionable ideas: tax cuts increase revenues and defense spending doesn’t drive the deficit.

The idea that lower tax rates lead to greater revenues is partly a misapplication of Laffer Curve theory. Economist Arthur Laffer described the relationship between tax rates and tax revenues and concluded that revenue would be zero at both a 0 percent rate and a 100 percent tax rate, but would peak somewhere in between.

Unfortunately, Laffer’s theory alone does not tell us enough about the shape of the curve to judge the impact of any given tax change. All we know is that as rates rise above zero, revenues first increase, and then at some point, they begin to decrease as the tax chokes off economic activity. But we don’t know with any precision which rate is associated with maximum revenue. Theoretically, it could occur anywhere; it is an empirical question.

It seems doubtful that cutting relatively low tax rates will increase revenues on its own. If, for example, the income tax rate changes from 15 percent to 12 percent, as it does for many workers under the 2017 tax cut, it is hard to imagine a lot of people entering the workforce or signing up for extra overtime just to get an additional three cents on each new dollar of income.

While many of these workers will spend more of their higher after-tax income, this additional spending is unlikely to generate enough new revenue to offset the impact of lower tax rates. As a result, the net effect of these personal income tax cuts is to increase the deficit.

The 2017 tax reform also notably broadened the tax base by limiting the deduction of state and local taxes, by capping mortgage interest deductions somewhat, and in a few other ways. But those provisions will not close the revenue gap resulting from the tax cuts. The economy should grow as a result, but federal government deficits will rise in spite of that.

While we might welcome tax cuts from a moral and economic growth perspective, we should avoid unrealistic estimates of their effects. Unless accompanied by sufficient spending reductions, lower taxes today that are unmatched by spending cuts have to be paid for in the future through tax hikes, inflation, or lower economic growth (as increased government borrowing crowds out private capital formation).

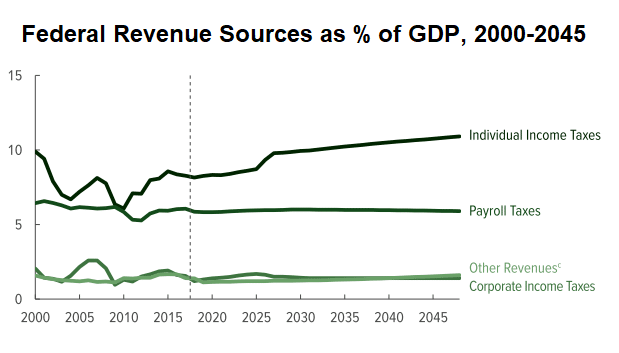

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts that revenues as a percentage of GDP will decrease through 2025 mostly due to the bill’s decreases in individual income tax rates. While the CBO estimates that tax reform will benefit the overall economy (particularly from business tax cuts), these benefits are insufficient to offset losses in income tax revenue. Corporate and capital income tax revenues represent only roughly 1.3 percent of GDP, while individual income tax revenues make up nearly 10 percent. Even as the model assumes overall economic growth, tax revenues as a share of GDP fall over the next eight years due mostly to the individual income tax cuts.

Another Republican argument that undermines fiscal reform is the assertion that defense spending isn’t responsible for the deficit. As with the tax cut/revenue increase meme, it stretches a fair observation to an inappropriate conclusion. It is true that in constant dollars defense spending is about the same as it was in the late 1980s, and also true that the explosion of entitlement spending is largely responsible for the run-up of the national debt.

Yet all spending contributes to the deficit equally. The deficit is simply the gap between expenditures —whether on entitlements, domestic discretionary purposes, or the military —and revenues. A dollar increase in any type of expenditure increases the deficit by exactly one dollar.

Thus, it is misleading to say that defense spending does not contribute to the deficit. And, since it accounts for about 16 percent of total spending, the defense budget offers significant cost saving opportunities. Reducing military spending will not on its own balance the budget, but it could help to slow the flow of federal red ink.

If the purpose of defense spending is to purchase security, there are many reasons to think that the money is spent inefficiently, i.e. we could get the same security for less. The Defense Department is almost unique among federal agencies in its consistent inability to pass external audits. We also know that defense construction projects are spread across numerous Congressional districts to maximize political support at the expense of efficiency. So even those Republicans who believe that the military needs to do all that it is currently doing cannot convincingly argue that DoD could not achieve all its objectives at a lower budgetary cost.

Deficits in the Democratic Future

If and when Democrats regain control of the government, fiscal sustainability is unlikely to be high on their agenda. While budget balancing was a major priority and a major accomplishment of the Bill Clinton era (thanks, in part, to the Republican Congress), it was noticeably less important to President Obama, and no longer has a place on the Democratic checklist. Many Democrats decried the revenue loss caused by tax cuts, but ascendant thinkers on the left are even more dismissive of spending cuts, dismissing it as “austerity”. To them, collecting taxes is more about reducing inequality than it is about covering the costs of government.

Since Democrats target younger voters and use the language of long-term sustainability when discussing the environment, they ought to be open to ideas about budgetary discipline. After all, government spending today that is financed by borrowing will be a burden on citizens having to pay higher taxes or enduring inflation, or encountering economic decline in the future.

But, at this point, it is hard to imagine what kind of crisis might prompt Democrats to adopt serious budget balancing measures. While in the past, Republican rhetoric may have forced Democratic budget balancing action, that seems less likely going forward given the complete loss of Republican credibility on the issue.

A Place for Third Parties?

In the 1990s, Ross Perot’s Reform Party was a major impetus for balanced budgets. Although Perot was eccentric (and mistaken on some issues like trade), he correctly focused his major attention on the national debt. Back in the early 1990s, interest rates were much higher than they are now, and, as a result, interest on the debt was a major drag on the economy. Perot’s 1992 campaign emphasis on the national debt arguably drove Bill Clinton’s policies to combine tax increases and spending cuts to shrink the deficit. Newt Gingrich’s Contract for America made it a bipartisan effort that resulted in a temporary respite from massive deficits.

But that deficit plateau is now only a distant memory. During the George W. Bush years, Republicans, particularly, showed no spending restraint either domestically or militarily and ended with a financial crisis that both major political parties thought justified massive deficit spending. The recession, low economic growth and stimulus package ambitions of the Obama years accelerated the trend. Low-interest rates moderated the need to finance debt with more debt, but that is coming to an end. Many trillions in new debt will soon need to be refinanced at higher interest rates.

With the Republicans back on a spending spree, could a third-party again play the role of the Reform Party? The two third parties that exist nationally, the Green Party and the Libertarian Party, have very different philosophies. The former is especially ill-equipped to act as a proponent of deficit reduction. While Greens favor lower military spending and higher tax rates, they have grandiose domestic spending plans. Also, like progressive Democrats, they tend to believe that austerity is an evil, foisted on us by the greedy rich.

Libertarian views are more compatible with fiscal sustainability. They favor across-the-board spending cuts; sparing neither entitlements, nor the military, nor subsidies for agriculture or business, nor education. And they often specifically deplore deficit spending.

Libertarians often advocate tax cuts while regarding tax increases as heresy. Taking a “starve the beast” approach, they trust that tax cuts will ultimately force spending cuts. The fact that we are now staring at trillion-dollar annual deficits as far as the eye can see, should belie the idea that limiting federal revenue necessarily limits federal spending. So a 2020 Libertarian Party presidential candidate re-enacting Ross Perot’s role of injecting balanced budgets into political discourse might have to depart from the usual LP script. Advocating across-the-board budget cuts with few or no tax reductions until the budget is balanced could be part of that. Tax reform to improve economic efficiency should also be pursued. This could involve a mixture of cuts mostly for business and capital, as well as tax base-broadening measures such as eliminating more special, carved-out income tax deductions, especially the mortgage deduction.

If the LP doesn’t fill the deficit reduction space, a new centrist party could also do the trick. While the emergence of a neo-Reform Party may seem unlikely as almost all of the political energy is being channeled toward opposing or supporting our 45th President, that ignores the fact that more Americans feel unrepresented by the major political parties right now than at any other time in history. As Morris Fiorina argues, the political dynamic is such that the Democrats and Republicans stake out extremes on many issues, leaving a plurality of Americans unsatisfied. Could a Howard Schultz or Mark Cuban give voice to concerns of currently unrepresented Americans by making a third-party effort? Perhaps Michael Bloomberg, if rejected by leftist Democrats, will try this route.

Procedural Reform

Relying on politicians of any stripe to balance revenues and expenditures has proven to be a fool’s errand. The temptation to spend the next generation’s money is simply too great for elected officials who face voters every two, four, or six years. One way to restrain politicians is to leverage the system of checks and balances by subjecting their budgetary actions to judicial review. In other words, we could use a Constitutional amendment to restrict fiscal imprudence. Free-spending legislators would then be forced to balance their desires to spend money against the difficulty of raising it. Likewise, Constitutional limitations on reckless spending would provide cover for fiscally prudent legislators.

In the 19th century, American states frequently became insolvent and failed to meet their bond obligations. Most reformed their constitutions to require balanced operating budgets, borrowing only to build infrastructure. The 20th century witnessed only one state default, Arkansas in 1933, and none have yet occurred in the 21st century. So, procedural reform improved state financial stability. This is true despite the many subterfuges states have used to pretend that their budgets are balanced, most notably underfunding their pension plans. But the restriction on issuing bonds to finance operating expenditures has acted as a bulwark against debt accumulation. The recent counter-example is Puerto Rico, where borrowing to cover operating deficits contributed to the Commonwealth’s fiscal tragedy.

Given the successful experience at the state level, a federal constitutional balanced budget amendment has some promise. Republicans control Congress but failed to pass such an amendment, House Joint Resolution 18, in April. It called for a balanced budget 10 years after enactment along with a cap on total spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product. The resolution had two loopholes: First, a three-fifths vote of both the House and Senate would be enough to override the requirement and pass an unbalanced budget. The March omnibus bill surpassed this level of support in the Senate and came within five votes of getting 60 percent of the votes in the House, showing how easy it would be to get around this requirement. Second, the balanced budget requirement would not apply when a declaration of war is in effect. The United States has been continuously involved in (although not Congressionally-declared) wars since 2001 with no end in sight. So a balanced budget amendment could simply lead Congress to replace its Authorization to Use Military Force against terrorists with an outright Declaration of War: a distinction without much of a difference.

Further, since economic orthodoxy calls for the national government to stimulate the economy by deficit-spending during recessions, the balanced budget amendment is not popular with policy analysts. The fact that the balanced budget requirement could be easily overridden does not seem to soften this opposition. Nor does the historical failure of countercyclical economic policy quell their concerns. Could a balanced budget amendment be made more effective and ideologically palatable? Perhaps the three-fifths majority override could be replaced with an exception based on negative economic growth. Thus, if GDP growth reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis falls below 0.0 percent in any quarter, the balanced budget requirement could allow a modest deficit for the remainder of the fiscal year.

We would also recommend taking out the spending limits which are unrealistic given the increasing numbers of entitlement recipients. By weighing down a fiscal sustainability measure with small government language, Congressional Republicans sabotage the odds of this amendment ever being enacted, given the need for it to be adopted by both blue and red states.

Perhaps there are procedural reforms that could impose incremental spending discipline on Congress, rather than relying on a year-end balance. One option might be to elevate Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) rules to constitutional status. Under PAYGO each individual spending bill has to be deficit neutral or deficit reducing.

Congress enacted PAYGO, Pay As You Go, in 1990 and it restrained spending into 2002. It had a less effective reincarnation a few years ago. Because PAYGO was only implemented as a statute, Congress has been free to circumvent it by majority vote, as it does constantly. A PAYGO constitutional amendment would require legislators to bear the political cost of raising revenue whenever they increase spending. It would give them political cover to vote against excessive spending by criticizing the concomitant taxes.

The Price of Inaction

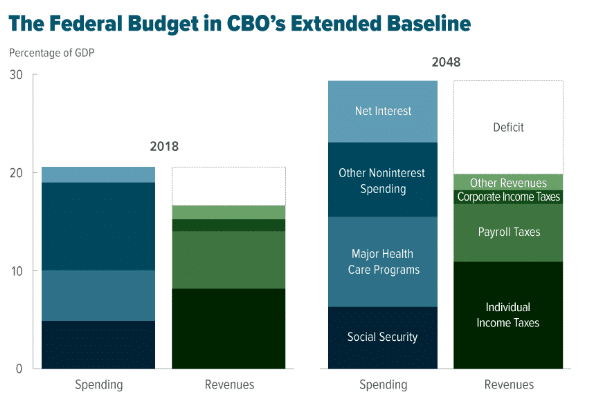

Barring procedural reform, it is hard to see how we avoid another string of trillion-dollar deficits. Indeed, another major recession could trigger multi-trillion-dollar deficits. This ongoing failure to balance revenues and expenditures will hasten the date of America’s fiscal reckoning. The debt accruing every year is reaching levels where within the next three decades the interest payments on our debt will amount to a significant portion of GDP. CBO projections show federal interest costs rising from 1.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 6.3 percent of GDP in 2048.

Under the CBO’s forecast, the public held debt-to-GDP ratio will surpass 150 percent by 2048 with annual deficits exceeding 8 percent of GDP. The risk is high that bond investors will stop accepting this type of fiscal performance, and the risks of inflation and default that it may cause. While a catastrophic devaluation of the US dollar seems most likely, an outright Treasury default with an attendant disruption of capital markets is also possible.

At a minimum, every dollar borrowed in the present requires one of three things: raising a dollar plus interest in taxes in the future; imposing a hidden tax of inflation to repudiate it; or undergoing ongoing high interest-rates as debt that comes due is continually rolled over. As the national debt continues to exceed GDP, a stagnant economy and political unrest will result. Default is unlikely in the next few decades, but how do we avoid it if we long remain on the same track?

While the idea of constraining politicians through constitutional measures may sound appealing, in the end, these will be ineffective unless the American public demands fiscal prudence.