Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy is proving to be bad news not only to municipal bondholders but to public employees and retirees as well. Last year, Puerto Rico’s government stopped making employer contributions to the island’s three pension systems, shifting them to pay-as-you-go plans. Members of the Employees Retirement System are no longer accruing new service credits; their employee contributions are instead going into a defined-contribution plan.

The government enacted these changes at the behest of Puerto Rico’s federal oversight board, which was created by the US Congress in 2016. However, the Puerto Rican government is resisting an additional reform being demanded by the oversight board: means-tested cuts to the pensions of current retirees. The board wants to achieve an overall benefit reduction of 10 percent, with the burden falling mainly on relatively high-income pensioners. While those receiving pensions below the poverty level would not see any cuts, pensioners receiving the largest benefits would face reductions of as much as 25 percent.

The domestic support of retiree benefits is an understandable political position from the current leaders of Puerto Rico. However, Congress created an oversight board and gave it the power to control Puerto Rico’s budget as the price of giving Puerto Rico access to federal bankruptcy court. Because Puerto Rico’s elected officials had proven unable to address the Commonwealth’s fiscal crisis, they needed Congress to provide them relief from having to make debt service payments. According to a recent GAO report, Puerto Rico has now defaulted on over $1.5 billion of interest and principal.

A Chronic Problem

Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis has been long in the making. In a 2016 Mercatus Center study, I traced many of the problems to the government’s reliance on debt issued by public corporations starting in the 1940s and to a translation error in the 1952 Constitution that allowed the government to borrow to cover operating expenses.

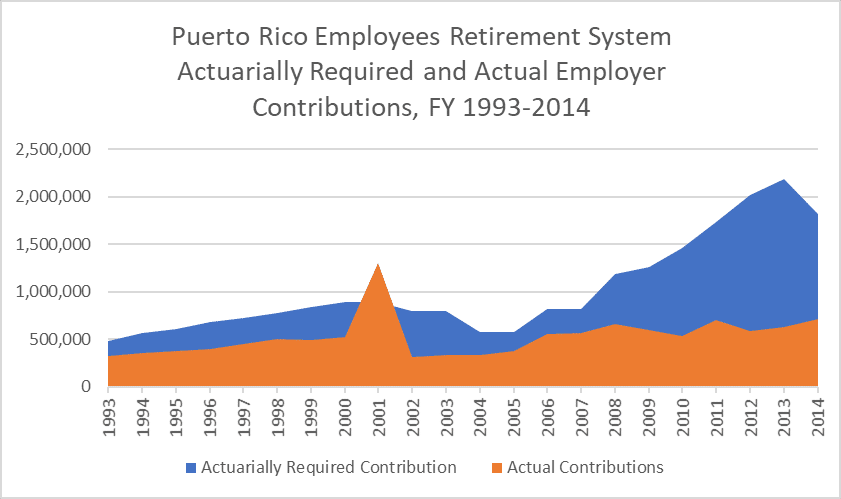

Puerto Rico’s pension woes were also long in coming. As the accompanying chart shows, Puerto Rico’s government employers persistently underfunded the island’s Employee Retirement System. During the 22 fiscal years ending June 30, 2014, the full contribution was made only once — when the Commonwealth government applied proceeds from the sale of its telephone monopoly to the pension system.

Even if employers had paid the full actuarially required contribution (ARC), the system would have remained underfunded. The ARC was too low due to an overly optimistic assumed rate of return. But, by failing to pay even the underestimated ARC, the government allowed the system to become deeply underfunded.

In 2008, Puerto Rico tried to remedy ERS’s funding crisis by issuing $3 billion of Pension Obligation Bonds (POBs). When a government resorts to POBs it is essentially gambling that the borrowed funds will generate investment returns greater than the interest it must pay on the bonds.

While it is true that pension funds can generally outperform municipal bond coupon rates, there are some important caveats. First, because POBs are not tax exempt, they carry higher interest rates than ordinary municipal bonds to attract investors. Second, even back in 2008, Puerto Rico already had relatively poor bond ratings, further escalating the interest rates it was obliged to pay. Many of the Puerto Rico POBs carried coupons above 6 percent — not far below ERS’ assumed rate of return of 7.5 percent.

Then there is the issue of timing. While a pension fund may return 7 percent or more over the long term, annual returns can fluctuate wildly. In retrospect, Puerto Rico’s timing could not have been much worse: it borrowed funds to invest in capital markets that were collapsing in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Between early 2008 and early 2009, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined by about 50 percent.

ERS disclosures do not allow us to see precisely how poorly the investments purchased with the POB money performed, but we do know that the total value of the system’s assets fell from $5.77 billion on June 30, 2008, to $5.07 billion on June 30, 2009 – a decline of about 15 percent. One saving grace for ERS is that a lot of its assets were held in cash or cash equivalents. Although that is not normally a good policy – since pension fund assets should be invested for the long-term — in this case, the ERS’ heavy use of cash cushioned the blow.

Conclusion

In Puerto Rico, a persistent failure to pay required contributions and poorly timed Pension Obligation Bond issuance has led to the collapse of its defined benefit Employee Retirement System. As a result, the system will not be there for new employees, while current employees and retirees will likely receive less retirement income than they expected.

The moral of the story is that imprudent pension fund management can have serious consequences for public employees. While it is now too late for Puerto Rico, public employees in the rest of the US should ensure that elected officials are properly funding the pension promises that they have made and that they avoid the use of risky strategies like Pension Obligation Bonds to paper over shortfalls. As stock indexes once again flirt with all-time records, downside risks are especially pronounced. Now is not the time to gamble with public employee’s retirement security.