Transportation for America, a division of the progressive advocacy organization Smart Growth America, is currently running an online campaign urging Congress to split federal surface transportation funds equally between highways and mass transit. At current funding levels, this would mean more than doubling mass transit’s federal subsidies.

Transportation for America’s (T4A’s) allies in Congress introduced a nonbinding resolution “declaring that public transit is a national priority which requires funding equal to the level of highway funding.” But, despite its lack of force, the resolution has currently managed to garner support from less than 10 percent of members of Congress, all from the left flank of the Democratic Party.

This symbolic effort coincides with the collapse of mass transit ridership in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, making aggregate funding parity a particularly tough sell to those watching travel trends. But what ought to make it an even tougher sell in the long-term is the large mismatch between pre-pandemic transit funding and transit ridership was already quite favorable to transit.

According to the most recent National Household Travel Survey (2017), automobiles accounted for 81.8 percent of person trips nationwide. Transit accounted for just 2.6 percent of person trips. Yet T4A’s main complaint is that transit only receives approximately 20 percent of total federal highway and transit funding—nearly eight times its 2.6 percent share of person trips—and that this funding share is too low.

It’s important to note that federal funding is only about one-quarter of total government spending on surface transportation. Adding state and local contributions, mass transit’s share of total highway and transit spending by all levels of government rises to nearly 30 percent, according to 2017 data published by the Congressional Budget Office.

And what were Americans getting in return for transit’s outsized share of pre-pandemic surface transportation funding?

According to the Census Bureau, working at home overtook transit’s share of journey-to-work trips in 2017. The 2018 data from the University of Minnesota’s Access Across America series show that U.S. auto commuters in the 50 largest metropolitan areas can access 46 percent of metro area jobs within 30 minutes (one hour of bidirectional daily commuting) compared to just 8 percent of jobs being accessible by mass transit within 60 minutes (two hours of daily commuting).

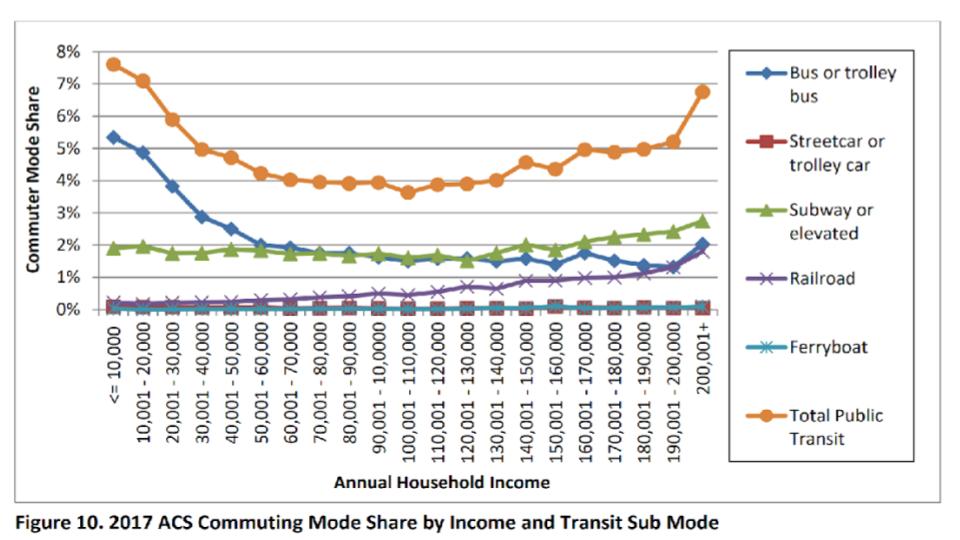

In recent years, transit agencies have increasingly focused on costly rail expansion projects aimed at attracting “choice riders,” those riders with the means to pay for their own transportation and who have access to private alternatives, at the expense of low-income transit-dependent riders who tend to rely on buses. As a result, the relationship between transit commuting and household income looked like this pre-pandemic:

With the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, mass transit ridership collapsed as Americans understandably feared sharing crowded spaces with strangers.

By August 2020, data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics showed rail transit ridership was still down 74 percent from the previous year but bus transit was only down 52 percent. Throughout the pandemic, monthly bus transit ridership has exceeded rail transit ridership, which follows several years of rail ridership surpassing bus ridership nationwide. This reflects the fact that most of the affluent rail riders to whom transit agencies have been catering in recent years are still working from home while low-income bus riders are employed in occupations less suitable for telework and must commute during the pandemic.

In contrast to mass transit’s dismal recovery to date, vehicle-miles traveled by highway vehicles is now down by only around 10 percent of the pre-pandemic baseline.

Taken together, transit’s status quo 20 percent federal funding share looks even more generous for a mode that is currently moving around 1 percent of total person trips. And that 20 percent doesn’t include the $25 billion in supplemental the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) funding, which amounted to nearly two years of pre-pandemic federal transit funding, while highways did not receive any supplemental CARES Act funding.

With working from home increasingly looking to be the “new normal” for many jobs, a significant share of the affluent rail commuters that transit agencies spent recent years chasing may not return. Due to the same potential long-term shift to telecommuting, urban peak-hour congestion on highways may be diminished going forward. These changes may force planners to rethink surface transportation funding. For example, fewer physical capacity expansions of both highway and transit systems may be needed to maintain the performance of our surface transportation networks, which are typically sized to meet rush hour commuting demand during the workweek. If these trends hold, this ought to result in substantial savings for taxpayers.

Rather than increasing the share of federal funding for mass transit systems that may never recover their pre-pandemic travel volumes, a wiser approach would be following recommendations made by Commuting in America author Alan Pisarski in a recent piece for Reason Foundation. Pisarski recognizes the unprecedented amount of uncertainty surrounding travel behavior and proposes five steps transportation policymakers should take to minimize their exposure to this risk:

- Call a short-term moratorium on all expansion-based transportation investment during the uncertainty of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Focus on improving the condition of the existing system—not just restoring, but modernizing.

- Assess ways to determine the role and prospective impacts of work at home trends—which already exceeded transit in share in 2017.

- Focus further on shifting transportation funding to be responsive to the accessibility needs of lower-income populations.

- Emphasize a strong focus on private sector solutions to respond to needs in this transportation world—utilizing the disruptive technologies that can serve users’ needs rapidly.

That being said, there is a more defensible case for equalizing federal transportation funding, but not in the way T4A envisions. Low-income travelers could be given transportation vouchers to use on whichever mode best suits their particular needs at a particular time. This would not only give low-income Americans more choice between different travel options, but it would also help bring their standing to parity with the affluent choice riders in the eyes of transit agencies, which have too often neglected their transit-dependent users.