This analysis discusses a five-step approach to understanding and addressing the new challenges that preceded, and now are intensified by, the COVID-19 pandemic and economic events of this year. The way that we react to them will be crucial to the nation’s transportation capabilities in the future. The COVID-19 pandemic and the governmental responses to it have reduced overall travel activity and shifted demand to different locations and modes of travel. Demand has shifted away from any form of concentration of passengers in vehicles and terminals, or even at potential destinations of travel. There has been a major shift to relying on household vehicles for any travel demand since there is less personal exposure to others.

1. Call a moratorium on all expansion-based transportation investments—for the obvious reasons.

While being willing to accept some absolutely clear and verifiable capacity needs, we must place a hold on transportation expansion investments, at least until the dust settles. The possible exceptions foreseen could be expansions that have already begun and need to be finished, such as bridge expansions, truck access to ports, storm responses, or natural disasters.

Even before the pandemic and recession—back in the fall of 2019—it was clear to transportation analysts that we were in the most difficult period in our professional lifetimes in which to forecast demand. The central issues were linked to technological and demographic changes.

The focal technological questions were examining the speed of arrival and the ultimate characteristics of autonomous vehicles (AV). Forecasts for the arrival of full-scale AV were anywhere from five to 50 years, and expectations were for a surge in travel volume or a decline. Who would own the vehicles: Hertz, Uber, General Motors, individuals, or governments? The new tech communication tools disrupted the taxi world, transit, and other traditional options.

There were also other questions. Demographically, the central challenge was where would the future skilled workforce come from? Would the retirement-age Baby Boomers work longer? Would the country import workers? Would we hope for the best? Shifting from child-centered travel households to an elder-care focus was on the horizon. Instead of you taking your kids to the dentist, they’d be taking you.

Travel growth that had been close to zero or negative during the 2007-2009 recession experienced a brief recovery but dwindled by 2018. Highway miles of travel grew by a meager 0.8% in 2019. Growth rates for the upcoming decade (2020-2030) were forecast at 1% a year. The only real growth sector was expected to be aviation.

Then COVID-19 hit and all of those very limited forecasts became almost foolishly optimistic. Travel by all modes decreased dramatically through the first half of 2020 and prospects for recovery and growth were not much more than conjecture. Modes that required certain levels of demand to justify services—rail, air, charter buses, cruise ships—sharply curtailed capacity.

At present, it is impossible to answer “when will we be back to the travel levels of 2019?” Without falling into talk of a “new normal,” at a minimum we can see uncertainty for the next several years. At the same time, fuel taxes, sales taxes, and general revenues that fund federal state and local transportation needs have shown massive declines.

With the present dominated by uncertainty in all aspects of travel demand, any proposals for capacity increases have zero credibility. Any modal option predicated on responding to congestion must be suspect. Thus, a hiatus, or maybe a moratorium, on building new facilities is the appropriate policy response. Auto travel, requiring no more than one person to justify a trip, has shown greater recovery.

2. Focus on improving the condition of the existing system—not just restoring, but modernizing.

At this time, the main focus could be the reconstruction of the Interstate Highway System, improving operations to assure safety and environmental enhancements, and rehabilitating— for safety purposes—existing rail transit systems.

In this environment, calls for transportation infrastructure spending need wary—even scrupulous—examination. Even in areas seeing substantial population growth, any investments based on forecasted travel growth must be suspect. Many projects require not just years but decades to develop, and proponents bear the burden of providing plausible situations for future dates that can justify the investment.

In this period, the wise public policy course is to recognize the massive backlog of transportation investment we already have. Bringing our transportation systems up to appropriate standards and investing in them should be the starting point for programs.

The National Highway System needs on the order of a trillion dollars in investments to restore and modernize the system. Looking at the physical condition of the Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago transit systems, restoration investment is a matter of safety as well as efficiency. The more modern transit systems developed in our time—Washington, D.C., and San Francisco—have already reached the level of massive needs for rehabilitation. All in all, the major transit systems could similarly identify ”trillion” as the basic investment level.

Certainly, no transit system—given six years of declining ridership and now the very serious health concerns of rail and bus riders—should be expanding while its massive rehabilitation needs are unmet. A national moratorium on the expansion of services along with efforts to rebuild, renovate and modernize should be the basic national infrastructure theme.

3. Assess ways to determine the role and prospective impacts of Work at Home trends—which already exceeded transit in share in 2017.

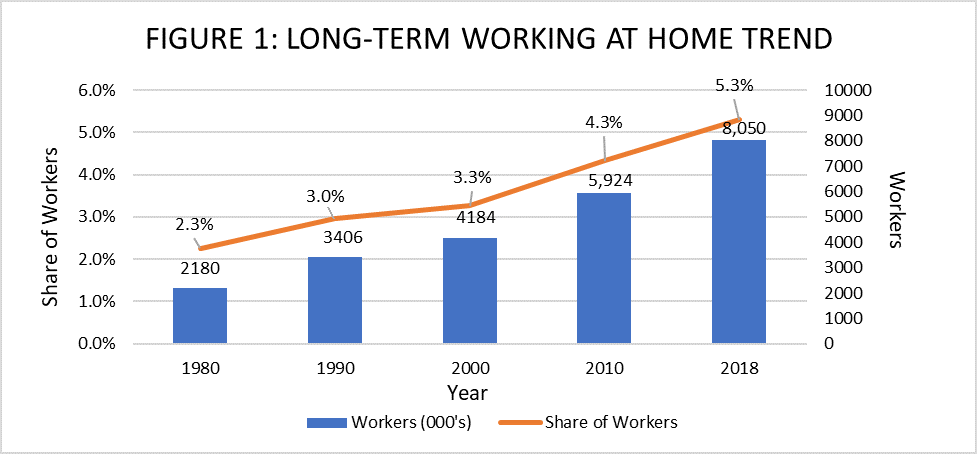

In addition to the above challenges, we have also seen a new world emerging regarding working at home. Working at Home (WAH), has been the fastest-growing “mode” of travel to work in America since 1970, growing at twice the rate of worker growth. In 2017, more than 5% of “commuters” worked at home, surpassing the percentage of people across the country that used mass transit. Working at home now has the third-highest share of work travel, trailing only car-pooling at 9%, and driving alone at more than 76%.

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic coincided with the ongoing trend of a massive increase in workers shifting to working at home. Many of those workers, engaged in this forced experiment, have found working at home an acceptable or even attractive option, providing both time and cost savings. Perhaps more significantly, employers are finding it to be an effective tool with limited near-term losses in productivity and prospective cost savings in office size and location.

The evolution of working at home in the longer term will depend on current unknowns, such as which activities can be justified in terms of sustained productivity over time, and how team-oriented activities and the acculturation of new employees can be structured.

Heretofore, the great majority of those working at home were typically individuals conducting personal service businesses, whether incorporated or not. Instead of writing the next great American novel, they were creating the next great American software program. Those working in traditional activities that are not always computer-based, such as childcare, also represented a significant share of “employees” working at home.

The immense power of today’s home-based tools—smartphones, computers, printers, scanners, and the internet— empowered many small businesses. However, since 2010, and certainly now in the COVID-19 environment, large private corporations have been the major growth source. It is unrealistic for everyone who is working at home to continue after the pandemic eases, but there is a new tolerance—even acceptance for it—among employees and management.

Working at home doesn’t generate greenhouse gases, consumes far fewer resources, and does not require significant public investments in infrastructure. Lower greenhouse gas emissions, decreased traffic congestion, and lower financial costs—what’s not to like?

The entire workforce structure has been moving towards a more flexible environment in this century, accommodating the needs of the hard-to-attract skilled workforce and recognizing the increasing influence of working women, who are now close to half of the workforce. At the very least, we can expect an environment where a large segment of the workforce operates on a split workweek at home and a meeting place—perhaps two or three days on each side. Recognizing that roughly two-thirds of workers live in a household with other workers, this opens many opportunities for shifting residence locations that are focused more on access to other things people value rather than job access. In the past this has permitted people to optimize their housing or other non-work-related preferences, resulting in moving farther from the occasional workplace. In many cases, our massive communications connections will continue to increasingly permit the work-from-anywhere workforce to locate wherever they find it attractive—a beach, a forest, a mountaintop.

4. Focus further on shifting transportation funding to be responsive to the accessibility needs of lower-income populations.

In many cases, that means buses, vans, and jitneys. Anything on rails would be exceptional.

The skilled workforce will continue to be in demand wherever they choose to locate. Often their only work needs will be the internet, a highway, and maybe a large commercial airport. Most of their activities are not resource-based.

Many of the key work-related transportation questions will concern the less skilled, who typically need access to physical workplaces. These can be resource-based, involving minerals, farms, rivers, and ports in rural areas. More typically they can be floorspace-based, requiring commuting trips to various structures such as factories, warehouses, hospitals, shopping centers, hotels, restaurants, and construction sites to provide services. In some cases, these are in the center of the metro area, but more frequently they are located in suburban work locations. Serving these businesses’ needs will require a far more flexible structure of public and private transportation services.

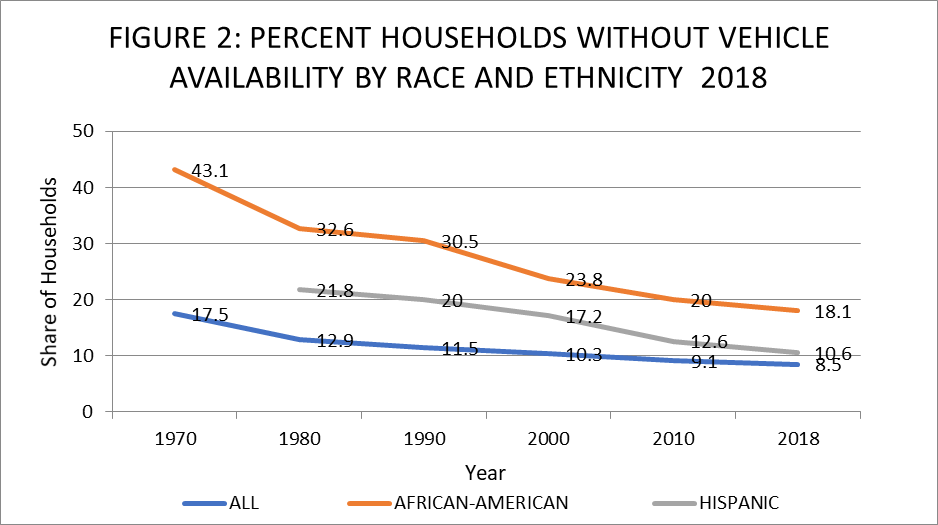

One of the great unrecognized advances in American transportation that benefits this population has been the increased longevity of the vehicle fleet, now at an average age of more than 10 years. Very serviceable, low-cost used vehicles are a major transportation benefit to lower-income workers. Both Hispanic and African American workers have made substantial gains in auto ownership, expanding their access to a broader reach of job opportunities.

Accessibility research in our major metro areas shows that in 30 minutes of travel, automobiles can reach approximately 30 times the number of jobs that can be reached by mass transit. Even among the best transit systems, such as Washington, D.C., cars can reach 90% of all the jobs in the region in 60 minutes, whereas transit can reach fewer than 11%.

5. Emphasize a strong focus on private sector solutions to respond to needs in this transportation world—utilizing the disruptive technologies that can serve users’ needs rapidly.

Rural connectivity will be a major concern. As jobs move farther into the suburbs, they become more accessible to rural workers, However, with the exception of resource-based employment, developing self-sustaining economic centers in rural areas has been very challenging. The tourism connection and the more recent tendency of retirees to locate near amenities like national parks will prove to be a major potential resource. One of the “resource-based” industries in rural areas will likely be providing services to newcomers to the area, as retirees seek services, health care, and attractive lifestyle amenities.

The almost-standard response over the years to these sorts of challenges has been to generate ideas for fleets of carpools, vanpools, and small buses. Frequently, this really is the answer, but it has suffered due to public constraints. To fully succeed, it will require eliminating or reducing the regulation of private vehicles that “compete” with transit. This may require action by governments to assist prospective operators by restructuring the many agencies that operate their many separate programs to facilitate new private initiatives.

All of the necessary responses seem to suggest small, focused entrepreneurial efforts rather than massive public programs. Private-sector roles in both highways and transit represent the real potential here. If the private sector, as part of a public-private partnership (P3), saw opportunities to invest in toll facilities and van-style services where they were willing to risk their money and become the great experimenters in new services, many “disruptive” new Uber- and Lyft-like experiments could emerge. Establishing a new program, or shifting public-private partnership programs to serve the capital needs of van- and bus-based start-ups along with traditional reconstruction needs could be effective.

The bus or vanpool approach has taken many forms:

- Private firms have developed their own bus fleets to deliver their employees. Microsoft has the third-largest fleet of buses in Seattle;

- Some companies have helped employees to operate a vehicle, owned by the employee or provided by the firm that can serve as a vanpool for groups of employees, given preferential parking, etc;

- The intercity bus industry has developed an important off-shoot of charter buses that deliver people to major job centers;

- In some cases, religious institutions have developed van systems to serve their members in daycare and other services; and

- Entrepreneurial opportunities, functioning like airport vans as something of a model, could emerge to serve large centers. It might be a great time to experiment with the many parked airport and hotel shuttles.

These are areas in which public, private, institutional, and market-based approaches can all play far greater roles than they have succeeded in doing so far. One reality is to establish how far they have succeeded and in what roles. It would not be surprising that the airport auto rental bus fleets and the airport-to-hotel fleets have a market role comparable in scale to public transit in many areas, which a Reason Foundation policy study pointed out more than two decades ago.

The lack of information on the functions the various systems perform obscures their potential to expand their services. We do not know how many fleets of vans/buses/vehicles there are and what they accomplish, how many passengers they carry, how far they travel, and at what cost. The new Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey (VIUS) being re-established by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics at the Census Bureau has the potential to address this issue. The transportation statistical system has a unique universe to sample to gain this information: the vehicle registration files of the states. The VIUS originally addressed only trucks and is now being redesigned to expand observations to further understand the vehicle fleets that serve the nation.

An important place to start an inventory would be in the federal aid programs that support local agencies assisting the elderly and disadvantaged. There are multiple programs, within the U.S. Department of Transportation and other agencies, among them the Section 5310 paratransit programs and Section 5311 rural and small city assistance programs under the Federal Transit Administration. These programs have been criticized as over-organized and over-scheduled, requiring previous day reservations and long wait times rather than their modern private counterparts serving on-demand travel. They can be modernized and expanded to reach low-income workers.

The new concepts of micro-mobility and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) are potentially helpful to van-based systems in the sense that more real-time information and rapid real-time responses could energize a new approach to transportation services. It would be delightful to believe that our transportation systems and public policies are up to these very serious challenges and from it more effective systems can emerge.