In the wake of unexpected events like natural disasters and pandemics, the concept of resiliency—in supply chains, infrastructure capacity, financial matters, and the like—is often heard as the motivating aspirational goal in reckoning with the aftermath. Chasing resiliency is a fairly routine matter in various aspects of risk management in the business world, and public sector entities are starting to pay more attention to the concept, especially in the wake of infrastructure condition and capacity challenges revealed through major urban flooding catastrophes like Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey. The same thinking should apply on the public finance front too, and with no real progress on improving public pension funding since the Great Recession and unfunded liabilities likely to approach nearly $2 trillion in fairly short order, it’s time for policymakers and stakeholders to embrace and pursue pension resiliency.

Some will, of course, argue that U.S. public pension systems are resilient already today due to several factors, including:

- Their long-lived investment horizon and long-term focus (e.g., the “stay calm, we’re long term investors, we plan for this” argument)

- A belief that long-term investment returns will revert to the historical mean

- The multiyear smoothing techniques employed in reporting investment returns, that then feed back into contribution rate calculations (which limit contribution rate volatility from the stakeholders’ perspective)

- They continue to reliably provide constitutionally protected benefits regardless of the whims in the market

Yet while there are some legitimacy and merit to every one of those commonly heard arguments, the instance of any one of them being true—or all, for that matter—is not sufficient to leap to an assumption of those pension systems being resilient in any real fiscal or policy-relevant way.

That’s because these are no longer theoretical arguments that require faith. We can look to our recent past to help guide better thinking. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the conversations among professional actuaries, their public pension system clients and policymakers tended to revolve around what, in retrospect, appears to be an utterly faith-based argument with the following two core components:

- Accepting a belief that despite the severity of the Great Recession and its impact on state and local budgets and pension funding, public pension funds were large and sophisticated institutional investors that planned for downturns and could “invest their way out” of what at that time was over $1 trillion in aggregate pension unfunded liabilities over the next 20-30 years.

- Accepting a belief that absent a crystal ball for investment returns, the concept of “reversion to the mean” is an acceptable benchmark by which to assume where long-term investment forecasts will land. After all, if your public pension plan has averaged a 9% investment return over the last 40 years, which many have, then would it not be reasonable to do so again into the future when it comes to long-term expectations?

But how did such faith play out in real life, having now over 10 years of experience to look back on? We’ve essentially had a lost decade in U.S. public pension solvency, for all practical intents and purposes.

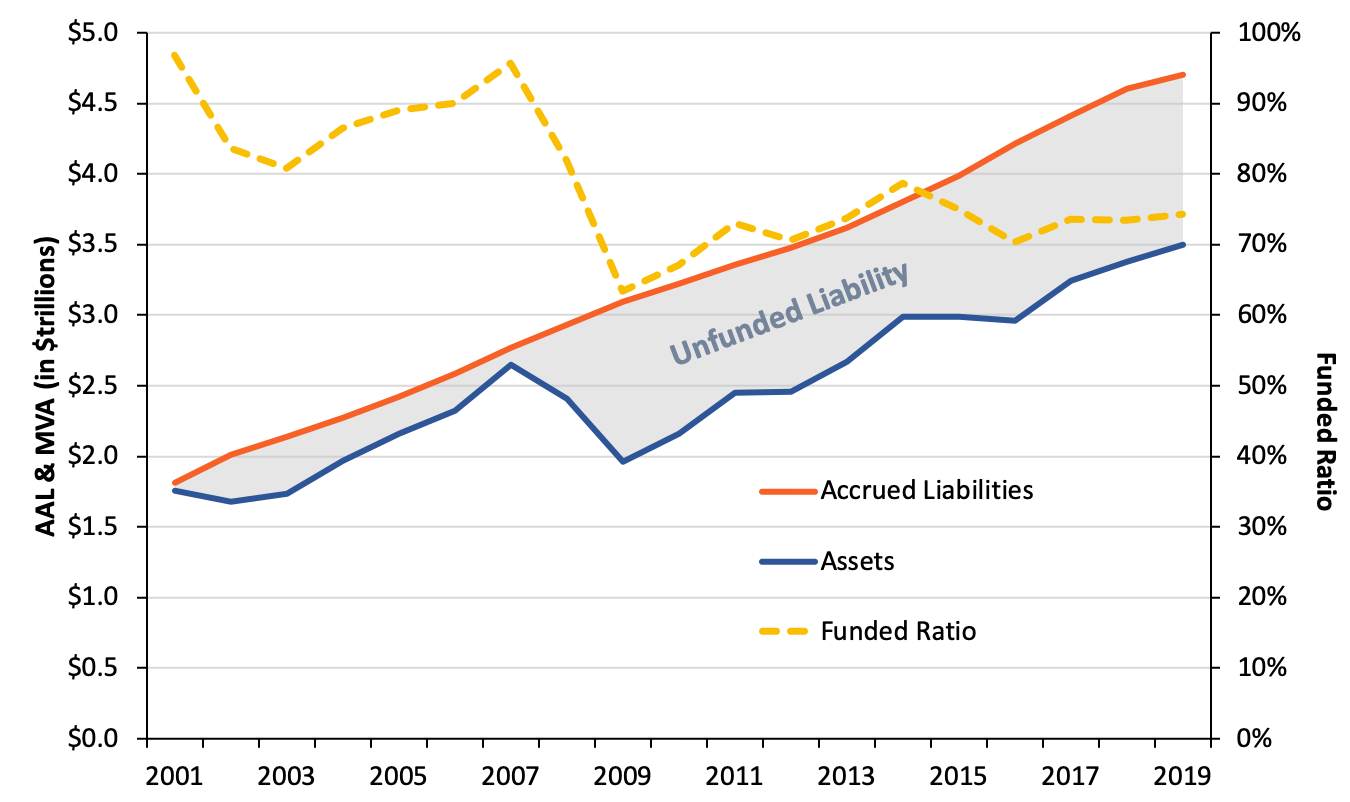

Public pension underfunding—the gap between assets and liabilities—skyrocketed during the Great Recession, jumping from $0.1 trillion at the end of fiscal year 2007 to $1.1 trillion by the end of fiscal year 2009. At the time, pension managers certainly recognized that they had their work cut out for them—and some systems made fairly minor assumption and plan design changes around the edges in an attempt to course-correct financially—but were mostly confident that they could chip away at this shortfall over time. Unfortunately, the experience that followed did not match their optimism. During a historic bull run in the equity markets, state public pension funds effectively made no progress on closing this funding gap, with national unfunded liabilities reaching $1.2 trillion by the end of fiscal year 2019, immediately prior to COVID (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Historical U.S. Public Pension Assets, Liabilities and Funded Ratio (2001-2019)

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of state-level pension data.

That’s not to say there was no progress at all. Aggregate funded ratios fell dramatically after the 2008 financial crisis but improved slightly over the following decade at the state level, going from a low of 63 percent in 2009 to an improved—but still woefully insufficient—74 percent in 2019. Another twenty years like the last ten would have theoretically pulled national levels closer to full funding, but even the most optimistic of market analysts would see the folly in that expectation given the roller coaster that is today’s volatile market.

Now, in the aftermath of losses caused by COVID-19, state and local governments will be facing the challenge of taking yet another significant hit to pension assets before they were even able to fully recover from the last drop. According to our estimates, 2020 unfunded liabilities are likely going to jump to between $1.5 trillion to $2.0 trillion, depending on investment returns in the current fiscal year, nearly wiping out a decade of gains since the last downturn.

This weak recovery and the likely 2020 loss of what little progress was made suggest that the “invest your way out” mindset is likely built on false hope. If public pension funds didn’t invest their way back to significantly improved funding after a decade long bull market, then why on earth would we think we’d be able to invest our way out now? How many times does Lucy pull the football until Charlie Brown stops trying to kick it, at least when it comes to improved pension solvency?

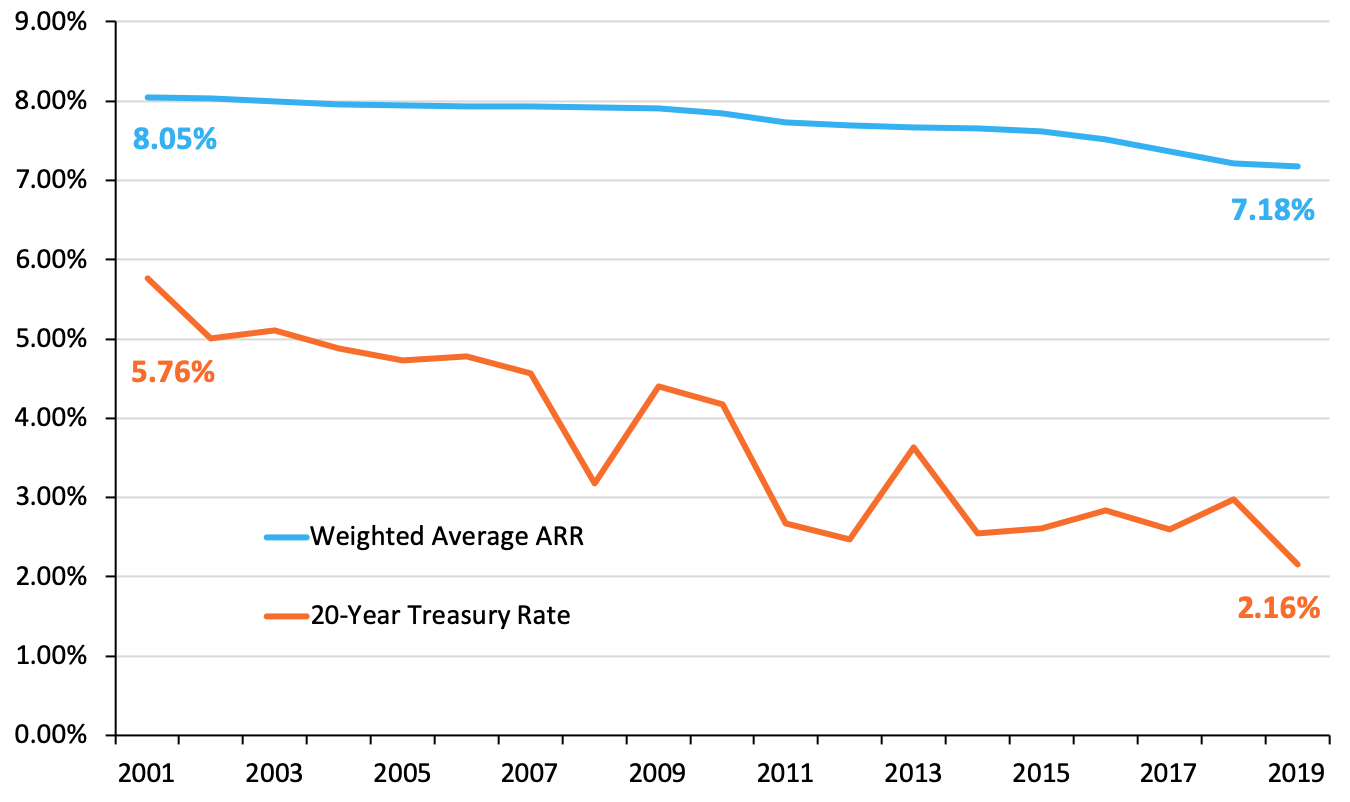

Now in fairness to savvy pension administrators and actuaries, it’s not that there’s been no progress at all. Public plans have steadily lowered their assumed rates of return over the last decade on an aggregate basis, from roughly 8 percent down to approximately 7.2 percent today. That is undeniably a positive thing on its own terms, to be clear, in that it reflects a growing awareness that the future may portend less in terms of market returns than in the past. But at a time when the implied risk premium—the difference between assumed rates of returns held by pension funds and a “risk-free” rate, such as the yield on 20-Year Treasuries—appears to be at an all-time high (in excess of a whopping 600 basis points, as shown in Figure 2), it seems almost self-evident that additional prudent steps to lower public pension discount rates further are warranted.

Figure 2: State Plans’ Average Return Assumption vs 20-Year Treasury Rate

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of state-level pension data.

Similarly, it’s not that plan directors and policymakers have done nothing at all. States like Michigan, Arizona, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and New Mexico have enacted smart reforms since 2015 that advanced reasonable ways to share risk more equitably between employers and employees and aimed to bend the long-term liability curve downward over the long run—and along with it, governmental appropriations. But most states made relatively smaller adjustments to their pension benefit structures and systems around the edges in the wake of the Great Recession, like meager adjustments to contribution rates, retirement ages, and the like.

Moving Beyond the False Hope of “Invest Your Way Out”

Perhaps the biggest “loss” in the lost decade for pensions was the lost opportunity for policymakers to more proactively address the problem. Looking forward, policymakers face a fundamental choice: do they revert to the “invest your way out” faith that has so poorly served them to date, or do they aim for a new operating principle, a new North Star, for underfunded pensions?

The latter is the prudent choice for policymakers moving forward given the severity of expected challenges to come in the near term. We should all want to see public pension funds achieve their long-term investment targets. It is, after all, in the best interest of all stakeholders. But that has not been happening consistently across shorter-term time frames, and that was the case prior to COVID-19. The strongest of pension funds still have to deal with unexpected situations like disasters and pandemics that are unforeseen (and we’re all getting a daily clinic in processing data and understanding forecasts and their foibles these days, which certainly has some high-level parallels with the vagaries of actuarial “what if?” projections).

It is time to admit that the hope-and-roll-the-dice model is failing state and local budgets. This policy outlook is disingenuous to employees, and it disrespects the sanctity of the pension promises made to retirees. Faith in “reversion to the mean” or “investing our way out” seems misplaced from a public policy perspective when daily we’re seeing news about negative oil prices, skyrocketing unemployment, a near-zero federal funds rate, global supply chain challenges, emerging corporate bankruptcies, and a lack of any clarity about where the future goes from here in terms of public health, economy, or many other factors.

Such faith in the future may have been a way to justify inaction in the past, but it is too shaky a foundation to base modern pension public policy on. If policymakers care about both taxpayers and retirees, then they should not play fast and loose with things like maintaining 7+ percent assumed investment return assumptions when those are ultimately based on faith in a “reversion to the mean” over the next 30 years, an outlook not justified by 10- to 20-year capital market forecasts. It would be vastly more prudent to hope for the 30-year returns to revert to the mean, while actually planning for a world in which they do not. In short, hope for the best, but plan for the worst.

Just as we need to build resilient public infrastructure systems that can handle and reduce the severity of unexpected weather disasters, we need to rebuild our public sector retirement systems in the US in a way that embraces the concept of pension resiliency.

This means adopting assumed rates of return tied to short-term forecasts and abandoning rates framed around long-term forecasts—not because we don’t believe the funds can achieve that, but because it’s a prudent way to build shock absorbers against certain risks, especially when taxpayers are exposed to such prominent financial risks associated with underfunded pensions.

This also means abandoning 30-year amortization periods to pay down future unfunded liabilities and containing pension debt payments to shorter (15-year or less) periods. This means using discount rates divorced from assumed rates of investment return to get a more realistic picture of the true liabilities that are going to be paid out to beneficiaries no matter what happens in the market, and then budgeting for that much larger, yet less risky, number. This means acknowledging that things like promising automatic 3 percent cost of living adjustments in an era of persistently low inflation ultimately undermines the financial health of the plans offering them.

In terms of the lost opportunity over the last decade, we should have been using the time between recessions to build a new generation of retirement systems at the state and local levels that look like much more like the federal government’s hybrid retirement plan, for example, or perhaps those fully funded public pension plans in places like Wisconsin, South Dakota and many Canadian provinces that have flexible benefit mechanisms built-in and keep contribution rate volatility fairly low. Entering a recession with $1.2 trillion in unfunded liabilities at still-too-high discount rates is a glaring signal that it’s time for a different approach.

Five Guiding Principles of Pension Resiliency

Resiliency may be the proper aim for pension funds today in terms of policy direction, but the US did not accumulate between $1 trillion to $2 trillion overnight, nor will it dig out from its pension debt challenges very quickly either. With pensions having been tacitly underpriced for so long, trying to squeeze additional pension contributions out of increasingly strained state and local budgets is going to be a tall order.

Things are likely to get worse before they get better. If, for example, pension plans started adopting more realistic accounting of their obligations by lowering their assumed returns, as the Pension Integrity Project would generally recommend to most, costs will necessarily rise as a result.

But the sooner plans embrace the financial and market realities they are actually living in—as opposed to seeing them as the way they would like them to be—the sooner they will recognize the true costs they face, and the sooner policymakers can begin to reckon with pension plan designs that have unintentionally left their systems too exposed to market shocks and volatility. Under that mindset, they can begin to fortify weak areas of the system to prevent the current situation from ever happening again.

This leads to five principles of pension resiliency to help guide the redesign process for US states and local governments:

(1) Resilient retirement systems rely on a governance structure designed to minimize the role of politics

Make no mistake, while the primary factors that drive unfunded pension liabilities—things like missed investment returns, negative amortization, demographic experience (like mortality) deviating from assumption—are technical in nature, the primary problems that have faced US public pension plans are driven by politics and the pension plan’s position in the political process. Policymakers (often with term limits) make long-term policies for pension plans while generally lacking any real expertise or understanding of the deep technical aspects. And there is often direct or indirect political pressure exerted by public employers on pension trustees to avoid making changes to contribution rates and assumptions that would result in higher annual employer contributions in the near term.

Worse, policymakers sometimes choose to set contribution rates in statute based on what they want to pay, as opposed to what the actuaries calculate is required to contribute each year to continue making pension funding progress. Some states (most notably, California near the turn of the century) have taken pension fund surpluses and, in the interest of raw politics, have used them to grant retroactive benefit increases to employees. Some states vest in the legislature the authority to statutorily grant “13th checks” and other supplemental benefit increases at their discretion depending on fiscal conditions in the pension plan, which risks spending down investment gains as they materialize instead of banking them to create a cushion that will likely be needed down the road when the next downturn hits. In other states, policymakers have a strong say over the pension fund asset portfolio, in other policymakers routinely try to substitute their political sensibilities over the pension plan’s investor team regarding different companies or sectors to invest in, or more commonly, to divest from.

By contrast, a resilient retirement system is one that is built to be politician-proof, except of course for the important role of public oversight and holding plans accountable. Major decision points facing US pension plans today—for example, the investment return assumption, the payroll growth assumption, the selection of a discount rate, the selection of contribution rates, and more—can be either entrusted to pension boards directly or—better yet—automated, tied to external benchmarks and contingency plans, and then set into motion and left to operate.

(2) Resilient retirement systems can take many forms but are designed to manage risk through autocorrecting features and policy guardrails

The Pension Integrity Project has been involved in the design of some major reforms of pension systems in recent years in states like Arizona, Michigan, Colorado and New Mexico that involved the introduction or expansion of innovations like cost-sharing mechanisms (e.g., 50/50 cost-sharing between employers and employees), automated changes in contribution rates or COLA levels, the use of more conservative assumptions (like Michigan capping the allowable assumed rate of return on the newest tier of its teacher pension plan at no higher than 6 percent), the use of graded pension multipliers that increase depending on service tenure (as in the new public safety tier in Arizona), and tying assumptions to certain external benchmarks (like regional inflation).

These efforts take inspiration from states like Wisconsin, which maintained full funding through a smart plan design that promises a core base benefit with the potential for an annual “annuity adjustment” up or down depending on the market performance of the pension fund. Employees of the Badger State have the expectation that benefits can be modified to a certain extent in the interest of maintaining full funding. South Dakota utilizes a similar approach that relies on adjusting benefit levels to keep the employer and employee contribution rate held steady.

Even Wisconsin and South Dakota pale in comparison in some ways to several Canadian provincial pension funds, which should serve as the basis for any new public pension benefit tiers in the United States. For example, US state legislators might understandably be envious of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, as just one example. This plan is 103 percent funded at a 4.60% discount rate, uses 50/50 employer/employee cost-sharing, uses a robust benefit adjustment mechanism tied to an objective decision framework, and has had employer/employee contribution rates hover in the 8-13 percent of payroll zone since the mid-1970s.

Another key innovation in recent years is the expansion of choice and alternative plan designs. We live in a world of more retirement plan design options than just pure defined benefit pension plans or pure defined contribution plans—including cash balance plans and hybrid plan designs. Rather than force all workers into a one-size-fits-all plan design approach, employers could offer a choice between a guaranteed return plan (like a cash balance or defined benefit pension plan) which would be attractive to those envisioning longer employment tenures, and a more portable plan design option(s) (e.g., hybrid or defined contribution retirement plan) geared towards workers that may not serve a full career in the same public service position. Arizona’s public safety plan, Michigan’s teacher plan, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s new hybrid plans for civilian workers and teachers all offer good examples.

(3) Resilient retirement systems are those that use realistic assumptions and are disciplined in maintaining full funding of their pension plans

Building off the previous principle—and in recognition of the many factors that drove $1.2 trillion in aggregate public pension underfunding in the US in the first place—to the extent that employers offer a guaranteed return plan option like a defined benefit pension or cash balance plan, it is essential that those plans be built on a foundation of realistic actuarial assumptions and rigid funding discipline reliant on making full actuarially determined contributions each and every year.

(4) Resilient retirement systems create a pathway to lifetime income for employees while avoiding intergenerational equity disparities, public service crowd-out, and runaway taxpayer costs

No matter what kind of resilient retirement plan designs are offered moving forward, it is critical that they all be designed to meet one core objective that respects every public worker for the time they serve the public—creating, even if just for a relatively short duration of their public service—a pathway to retirement security. If they are a traditional career worker in their 50s participating in a pension system, then that pathway is fairly clear. But if they are a 26-year-old starting a new public sector career that may not last long, then a professionally managed defined contribution plan design with strong contribution rates may serve the same purpose from the perspective of advancing retirement security.

(5) Resilient retirement systems assess—and plan for—downside risk

Most charts and figures related to pension funding and solvency that public pension plans show to US policymakers are based on the plan’s own adopted economic and demographic assumptions holding true and accurate, creating a path dependency of sorts on assumptions. In recent years, enhanced accounting standards and required financial disclosures have increased the amount of attention given to alternative scenarios that deviate from assumptions, and states like Virginia and Hawaii have adopted laws requiring routine risk assessment.

These are encouraging moves and over time will prompt much more active discussions related to pension risk management, but risk assessment alone is only part of the answer. Risk assessment needs to be accompanied by strong contingency planning and “what if?” thinking. For example, as mentioned earlier the South Dakota Retirement System regularly conducts a risk assessment process to understand if there will be a likely need for any benefit flex in order to maintain current employer contribution rates. At that point, the system undertakes a deeper contingency planning analysis to determine the scope and scale of the changes likely needed to get ahead of the problem, allowing the plan to provide substantive guidance to policymakers on the many aspects of needed reform.

Conclusion

In the world of investments, past performance is no guarantee of the future, but those managing pension plans cannot ignore the implications of the past decade and the current market shock. The fact that pension funds have experienced very little recovery since 2009 and are now facing yet another significant loss suggests that the design and assumptions in many public pension plans may not be well-suited for the current setting of market turbulence.

The Pension Integrity Project has for years suggested plans use stress testing to assess their ability to maintain solvency. Now, every single plan is experiencing a real-world stress event. When the dust settles on the immediate economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, pension stakeholders and policymakers should use this moment of clarity to recalibrate not only expectations, but the overall guiding principles of retirement security.

In the interest of retirement security for public workers and fiscal stability of state and local budgets, policymakers need to consider restructuring pension plans to reflect the principle of resiliency. In short, plans need to be structured to better withstand the market shocks that appear to be emerging more frequently in the modern era. There are already several examples of reforms and plan structures that can serve as roadmaps to policymakers seeking to fortify their government’s public employee retirement system against the increasingly volatile ups and downs of the market. Judging by the past couple of decades, the resiliency of retirement systems will largely decide how effectively—and at what cost—these plans will be able to continue serving their members and the public.