The Retirement System of Alabama (RSA), which last year managed over $45.5 billion in assets, recently acquired the CNHI LLC newspaper group, expanding its pool of non-traditional investments. Like any other public pension plan, RSA relies heavily on investment returns to fund the retirement benefit payments that have been promised to public workers. And while wading into non-traditional investments isn’t the standard, this approach can potentially help address the RSA’s disproportionately large investments in its own state economy, providing at least some geographical diversification in hopes of reducing investment risks.

RSA added the Montgomery, Alabama-based newspaper to its investment portfolio earlier this year. And this is not a small acquisition by any standard. CNHI LLC is one of the largest chains of local newspapers in the U.S., with The Valdosta Daily Times in Georgia and The Tribune Star in Terre Haute, Indiana, being just two of CNHI’s more than 100 newspapers and websites operating in 22 states.

Whether RSA’s new purchase will pay off and whether print newspapers have a positive future ahead of them is yet to be determined. With the growing digitization, now 43 percent of U.S. adults often get news from news websites or social media. Daily paid newspaper circulation has fallen since the 1990s, according to the Pew Research Center.

However, this is not the first time the state retirement system has invested in newspaper groups. As a matter of fact, CNHI LLC is a spin-off from Raycom Media Inc., which last year was among RSA’s top three investments by fair value (in form of debt and equity securities), standing at around $3.0 billion (roughly 8.6 percent of RSA’s portfolio). That is why RSA chief executive David Bronner feels “comfortable with the [new] investment.”

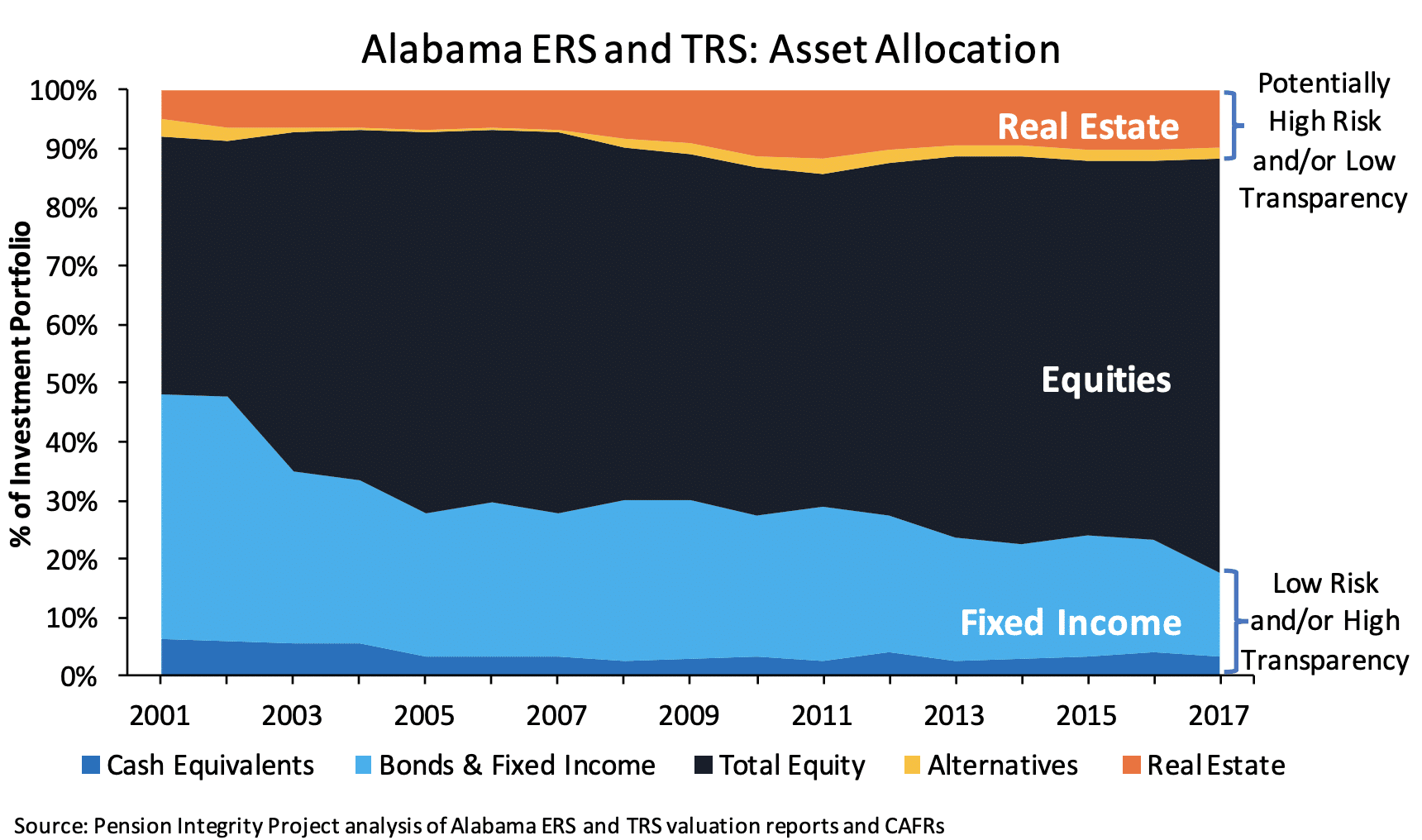

Interestingly, RSA already has an extended pool of non-traditional investments—golf courses, airliners and the largest office building in New York City, 55 Water, are just some of them. The New Water Street Corp., which owns and operates commercial buildings, is also among the retirement system’s top holdings. RSA historically focused on stocks but is increasingly seeking out alternative ways to invest, such as real estate (see figure below).

Note: Asset allocation values shown are for ERS and TRS plans combined, weighted by their fair value of investments

Overall, such peculiar investing is not out of the ordinary if you consider that many public pension plans have chosen to chase riskier, and unorthodox, investments in hopes of hitting what are often overly optimistic return assumptions. In fact, the “new normal” environment of lower returns that has settled in since the 2007-08 financial crisis has pushed many state and local pension plans to move away from safe fixed-income investments, and initially from equities, into riskier alternative investments (e.g. private equity, and real estate). The average allocation to such investments among state and local retirement systems has risen from 11 percent in 2006 to 26 percent in 2016, according to Pew Charitable Trusts.

As their investment risks increase, with more profound year-over-year investment return swings, public pension plans ought to counter that through de-risking methods and diversification. Diversification means investing in a wide variety of different types of assets and locations, helping to guard against unnecessarily large losses, if some allocations underperform relative to the others.

To their credit, RSA endorses this approach. As its own investment policy reads: “[t]he fund is to be broadly diversified across and within asset classes to limit the volatility of the total fund investment returns and to limit the impact of large losses on individual investments of the fund.”

But despite RSA – which last year was $15.3 billion in the red and only 70.9 percent funded – clearly stating its belief in diversification, it seems to be lacking in that respect when compared to other state systems. As we have previously reported, RSA invests more than 15 percent of its assets solely into the Alabama economy, mostly in equities (see graph below), which is more than most other state-level retirement systems in the U.S., second perhaps only to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, CalPERS.

But, such policies aimed at priorities beyond the retirement security of state or local workers almost always backfire. A 2016 Troy University study found that disproportionate investments in so-called Economically Targeted Investments (ETIs)—investments chosen based on their economic or social benefits (almost all of them are in-state investments)—have contributed to RSA’s asset underperformance and severe pension underfunding.

“We’ve got to invest in ourselves,” said David Bronner, head of the RSA, back in 2016. One of the reasons the retirement system wants to support the state’s economy, he said, is to ensure the state’s ability to make its pension contributions. However, this negatively effects the retirement system’s ability to generate higher returns.

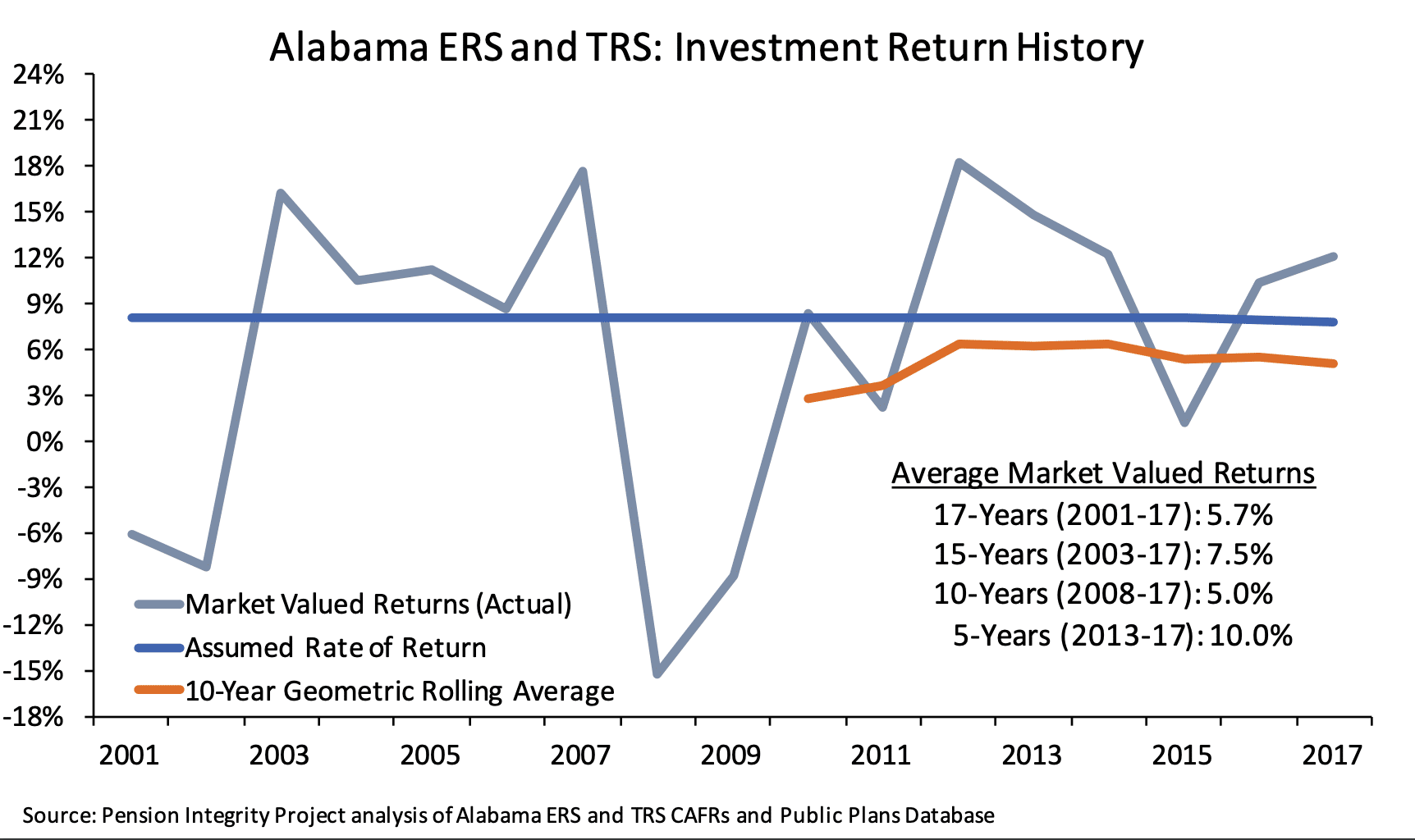

Notably, the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) and Employee Retirement System (ERS) combined have only returned 5.0 percent and 5.7 percent, on average, over the last 10 (2008-17) and 17 (2001-17) years, well below their ambitious 7.75 percent assumed rate of return (see graph below).

Note: Investment returns shown are for ERS and TRS plans combined, weighted by their fair value of investments

According to a study from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, despite most public pension plans investing relatively similarly, the difference in individual asset-class returns—not overall allocation, notably—is responsible for more than three-quarters of the historical underperformance of the average public pension plan compared to the top-performing one. This implies that prudent allocation and diversification within any particular type of investment (e.g. equities, real estate) could be much more effective in remediating asset underperformance than the way the total assets are allocated among these types of investments.

Last year, investment returns on RSA’s domestic and international equities were north of 17.8 percent and 19.7 percent, respectively. This is certainly encouraging. But, despite a few streaks of healthy annual returns, many publicly-funded pension funds, RSA included, are not out of the woods.

As Aaron Brown from Bloomberg writes, cumulative returns are usually lower than average returns, and extended periods of bad returns may not be made up with two-digit returns later down the road. Thus, diversifying by investing in a diverse pool of assets that behave differently to each other, such as index funds, is essential for curbing risks.

With the ever-present fiscal health concerns both on state and local levels, legislators in many states, such as Alabama, often seek ways to secure promised pensions while maintaining fiscal government prudence in the process. In Alabama’s case, de-risking and diversifying pension funds’ asset allocations to mitigate large losses should be part of that examination.