Pension liabilities are retirement obligations contractually promised to public workers. In any sense of the word, an unfunded pension liability is a debt, yet it is not treated the same as other government obligations. State and local governments have long engaged in the practice of issuing various types of debt instruments to finance infrastructure and other public endeavors. But, despite holding the power to levy taxes, these governments aren’t always able to repay those obligations.

The Panic of 1837 was a U.S. financial crisis that collapsed credit and commodity prices and triggered bank failures. During the seven-year period of economic depression that followed, several states defaulted on infrastructure bonds. In the 1920s and 1930s, Arkansas borrowed for highway construction but defaulted in 1933 during the Great Depression. These and other defaults led states to widely adopt constitutional and statutory limits on the issuance of general obligation (GO) debt, protecting both present and future taxpayers from fiscal imprudence.

Many public policy makers do not understand that public pension liabilities are not legally treated as general obligation-type debt and are not subject to the safeguards restricting GO debt undertakings. In some states, these pension obligations have even stronger claims on the full-faith and credit of the state than GO debt.

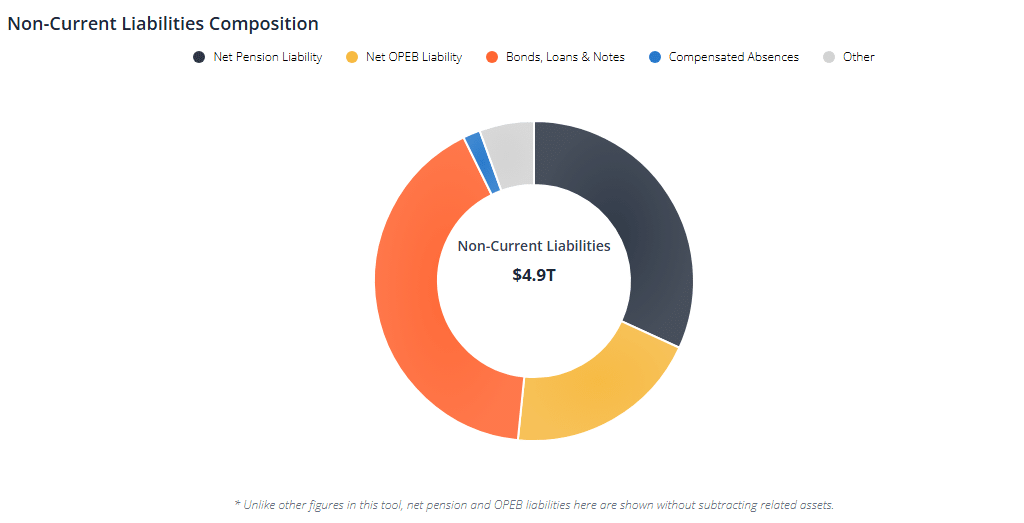

The lack of general obligation debt type safeguards constraining public pension liabilities has significant implications on the financial risk position of state and local governments, which currently have issued about $4.9 trillion in long-term debt. About $1.5 trillion of that, or 32%, is attributable to unfunded public pension liabilities—that is, the gap between currently held assets and the total estimated cost of public employee pension liabilities.

Therefore, it is important for policymakers to understand the policy rationale for general obligation debt limits and why public pension obligations in many states can be more serious than GO debt. Fortunately, there are ways to reclaim fiscal control, including new-tier reforms.

Distinguishing between general obligation debt and special obligation debt

General obligation debt is the gold standard of state borrowing. It is what most people picture when they think of “government debt.” GO debt is comprised of bonds backed by a state’s “full faith and credit” and unlimited taxing power. A state must legally commit its full taxing power to meet the obligation. This means the state is obligated to raise taxes or reallocate general revenues if necessary to cover general obligation debt liabilities.

Often issued via voter-approved bonds, GO debt funds are essential for long-term capital projects like schools, roads, and hospitals. Repayment draws from general revenues (such as sales and income taxes), making it a sacred pledge binding future taxpayers.

Special obligation debt, by contrast, is “limited obligation” financing, secured by specific revenue streams (such as tolls and utility fees) rather than general taxes. Examples include revenue bonds for water systems or lease-revenue bonds for buildings. Without taxing authority, special debt cannot burden the general fund, which generally isolates the risk to project-specific cash flows.

The distinction is important: GO debt’s impact on all taxpayers demands higher levels of scrutiny and constraint; special debt’s narrow scope and limited funding sources allow more unrestricted use. As a result, state laws (constitutional and/or statutory) commonly impose rigid caps on GO debt—typically 5-15% of assessed valuation or voter approval requirements—to prevent fiscal recklessness. These limits serve four policy imperatives:

- Taxpayer Protection: GO debt commits all future revenues, risking hikes or service cuts. California’s Proposition 13 (1978) capped GO at 1.25% of property values, shielding homeowners from spirals like pre-1930s defaults.

- Intergenerational Equity: Limits ensure current voters don’t mortgage future generations. New York’s Article VII caps GO at $0 without a referendum, forcing accountability.

- Fiscal Discipline: Caps curb pork-barrel spending. Texas limits GO to 5% of property values, prioritizing pay-as-you-go infrastructure.

- Credit Stability: Rating agencies reward low GO burdens with better credit ratings. Higher GO burdens result in lower credit ratings and higher borrowing costs.

Comparing general obligation, special obligation, and unfunded pension liabilities

According to Reason Foundation’s GovFinance Dashboard 2025, states, cities, counties, and school districts carry $4.9 trillion in total long-term liabilities, which are obligations due in more than a year. The bonds, loans, and notes category—which includes general oblication debt and special obligation debt—makes up about 41% of all state and local government debt. About 32% consists of unfunded pension obligations ($1.5 trillion) and about 20% ($970 billion) in net other post-employment benefits (OPEB)—mostly unfunded retiree health liabilities.

Government long-term liabilities

In many states, public pension liabilities are worse than GO debt

Unfunded pension liabilities represent the gap between a public pension plan’s promised benefits and the assets set aside to pay them. Such liabilities are not typically classified as traditional “debt” in the same legal category as GO or special obligation debt because they arise from contractual obligations to employees rather than formal borrowing.

But while these liabilities may not be formally called debt, in many states, they mimic—and in some cases even exceed—GO’s full faith and credit claim on general revenues. This has largely occurred because of various court decisions interpreting public pension benefits as unique contract rights that cannot be reduced or changed for current workers, even for their future employment periods or under state or local bankruptcy. Workers should receive the pension benefits they’ve already earned, but these court decisions go further and interpret varying statutory or constitutional provisions as creating an inviolable contract to provide the pension plan benefits existing at the time of hire without any impairment, even for future service (e.g., ‘the California Rule’).

The California Rule comes from a court decision holding that pension benefits cannot be “impaired,” interpreted to mean that a benefit promised to a government employee upon hire must continue to be offered for the duration of that employment. This ruling has faced legal scrutiny, with the argument that courts are interfering with the state’s law-making power by protecting not-yet-earned future benefits as if they were in a contract. The California Rule remains extremely relevant and a matter of ongoing legal discussion, as several states have seen similar rulings (Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Washington).

These priority rights to accrue pension benefits for future employment go well beyond federal ERISA law, which only protects benefits accrued to the present but not for future potential accruals.

States have GO-like pension liabilities, and they represent similar fiscal burdens on state resources

Five factors affect how much public pension liabilities resemble or exceed the burden of general obligation debt:

- Legal Enforceability: The level pension benefits are protected by the state’s constitution or statute.

- Judicial Precedent: The level of protection with which courts have treated pension obligations as contractual or enforceable, including future benefit accruals.

- Full Faith and Credit Implicitly Exists: The fiscal expectation that the state will pay, even without a formal GO pledge.

- Budgetary Priority: The extent to which pension payments are prioritized like debt service in budgets.

- Credit Rating Treatment: Whether rating agencies treat public pension liabilities as equivalent to bonded debt in risk analysis.

Since the above factors vary, in some states, public pension debt is prioritized similarly to general obligation debt. In others, pension promises exceed the level of priority given to GO debt. Using the GovFinance Dashboard, we compared selected states with stronger GO-like treatment (e.g., constitutional protections) to levels of net pension liabilities per capita.

| GO Debt-Like Category | Pension Benefit Protection Level | Select States | Net Pension Liability per Capita | Moody’s Credit Rating |

| Strongest GO-Like (Constitutional +Judicial) | Highest: Inviolable contract; full taxing power pledge | Illinois New Jersey Connecticut | $17,786 $10,601 $12,997 | A2 Aa3 Aa2 |

| Moderate GO-Like (Statutory + Judicial) | Medium: Contractual rights but modifiable with offsets | Kentucky California Mississippi | $7,790 $6,796 $3,847 | Aa2 Aa2 Aa2 |

| Weakest GO-Like (Common-Law/Statutory Only) | Lowest: Greater flexibility for benefit adjustment | Wisconsin South Dakota Tennessee | $1,159 -$13 $450 | Aa1 Aaa Aaa |

Source: Moody’s Ratings 2025 from various sources.

While a formal 50-state statistical analysis was not conducted and the states shown vary in terms of protections of future benefit accruals, this small sample shows a pattern: Of those included, the states that have the strongest legal constraints on changing public pension benefits tend to be in a worse position with regard to per capita net pension liability levels and lower credit ratings. The result is significantly higher borrowing costs—sometimes as much as 100 basis points for 10-year bonds.

Mitigating pension benefit inflexibility

While public workers should receive the pension benefits that they’ve already earned, overly rigid pension benefit protections limit the ability of state and local governments to engage in needed reforms to pension benefits and funding mechanisms, locking in potentially unsustainable pension promises despite market downturns, underfunding, or demographic and workforce shifts. This creates a feedback loop: Benefits accrue without adjustments, liabilities balloon, and states must divert larger portions of the general fund to amortize shortfalls. In contrast, states with more flexible structures can implement reforms (such as new tiers, hybrid plans, and contribution hikes) for future benefits, leading to lower relative liabilities.

States can take steps to mitigate public pension unfunded liabilities and inflexibility by taking pragmatic steps:

- New Tiers for New Hires with Reserved Rights: The new tier should reserve the right to make changes to yet-to-be earned retirement benefits in the future. This will avoid otherwise applicable constitutional or contractual impairment issues. An example is the 2011 Rhode Island pension reform, which created a new hybrid Defined Benefit/Defined Contribution plan for new hires.

- Defined Contribution (DC) Plans: A DC plan would help reduce the future growth of pension liabilities for new hires. An example is the action taken by Utah in 2010 to mandate a DC/hybrid plan for new hires.

- Move to Full Actuarial Funding: Implement full annual actuarially determined contribution rates with more conservative/less risky actuarial assumptions – particularly investment return/discount rates and shorter-term amortization schedules. This may raise current pension funding costs, but it will increase intergenerational equity.

- Challenge Overbroad Judicially Defined Protections: Seek to overturn existing judicial decisions regarding the inviolability of pension contracts even for future service. If successful, it will create flexibility in managing pension liabilities for future service while protecting already accrued benefits.

General obligation and other bonded debts have long been subject to robust safeguards and rigorous oversight, whereas unfunded pension liabilities have not, despite the fact that unfunded pension liabilities can pose an even more severe risk to state fiscal stability.

The key distinctions between general obligation debt and special obligation debt highlight why strict controls are essential for obligations that directly impact present and future taxpayers. Without comprehensive reform, including new-tier pension strategies and enhanced fiscal discipline, states face continued financial pressures and diminished flexibility for future budgets. Prioritizing prudent management of both general obligation debt and public pension liabilities is crucial to safeguarding taxpayer interests and preserving long-term fiscal health.