Does the privatization of government functions help underfunded public pension systems, harm them, or neither? The interplay between the privatization of government functions and its impacts on public sector pension systems is poorly understood and rife with false beliefs that can cloud policy discussions, as evidenced by an ongoing situation in Kentucky.

A recent article in the Lexington Herald-Leader reported on a growing trend in Kentucky towards privatizing public workers, submitting Western Kentucky University (WKU) as a prime example of this movement. In 2016, WKU decided to privatize over 200 of its hourly wage workers to be employed instead by a contractor, which included shifting the workers out of the state retirement system’s defined benefit (DB) pension plan and into the private contractor’s 401(k) plan.

While there were several budget-related reasons for making this move, reducing the ever-rising contributions that the university must make to the commonwealth’s public pension system was, according to university officials, certainly a driving factor in this decision. The Herald-Leader article rightly identifies the reduction of pension costs as one of the motivations behind the university’s privatization, but then presents an egregious mischaracterization by suggesting that WKU is using the privatization of its workers to skirt pension debt payments. Even worse, the article suggests that the newly privatized workers somehow still bear some responsibility in paying off pension debts accumulated in Kentucky’s struggling pension plan.

To fully comprehend this misrepresentation, one must first understand the increasingly complicated relationship between Kentucky’s public employers (including WKU) and the Kentucky Retirement System (KRS). Due to a variety of factors—notably the pension system’s investment returns well below assumed rates, underpayments of required contributions, and problems with funding methods—KRS has dipped into dangerously low funding levels.

Employees of state universities and most state workers, other than firefighters and police officers, are members of the KERS Non-Hazardous plan (KERS-NH), the largest division of KRS with a reported pension debt of $13.5 billion. KRS has just 13.6 percent of the funds needed to pay all of its promised pension benefits. Overseeing the retirement security of the majority of state employees, the KERS-NH plan is a major contributor to the fact that Kentucky has one of the worst-funded pension systems in the country.

WKU’s 2016 privatization of workers raised some concerns and sparked an ongoing legal battle with KRS, which claims the university and the newly privatized workers are still required to make contributions into the plan as if they had never left. KRS, along with the Herald-Leader article, incorrectly characterize the university’s move as a way to “game” the system, by having the outsourced workers benefit from KRS in excess of the contributions made on the affected employees’ behalf.

According to this mistaken line of reasoning, moving workers out of the pension plan abandons those workers’ growing retirement liabilities while removing contributions that would have come from those workers. Nothing illustrates this misguided argument better than a quote in the Herald-Leader piece from a former KRS board member, who said “Privatization is just another sneaky game they play that gives us more ‘pension orphans,’ which is what I call the employees whose liabilities are left in the system without any cash flow to contribute to them.”

While the above line of reasoning paints a compelling picture, the logic breaks down with a clear and accurate understanding of pension funding.

What do the critics of privatization get wrong here? They assume unfunded liabilities, or pension debts—discrepancies between how much a pension plan has and how much it needs to have invested now to be able to generate the returns needed to pay out all promised benefits—are attached to, and therefore need to be paid by, individual workers.

Simply put, pension plans do not treat unfunded liabilities this way, nor do they allocate employee contributions toward paying down pension debt.

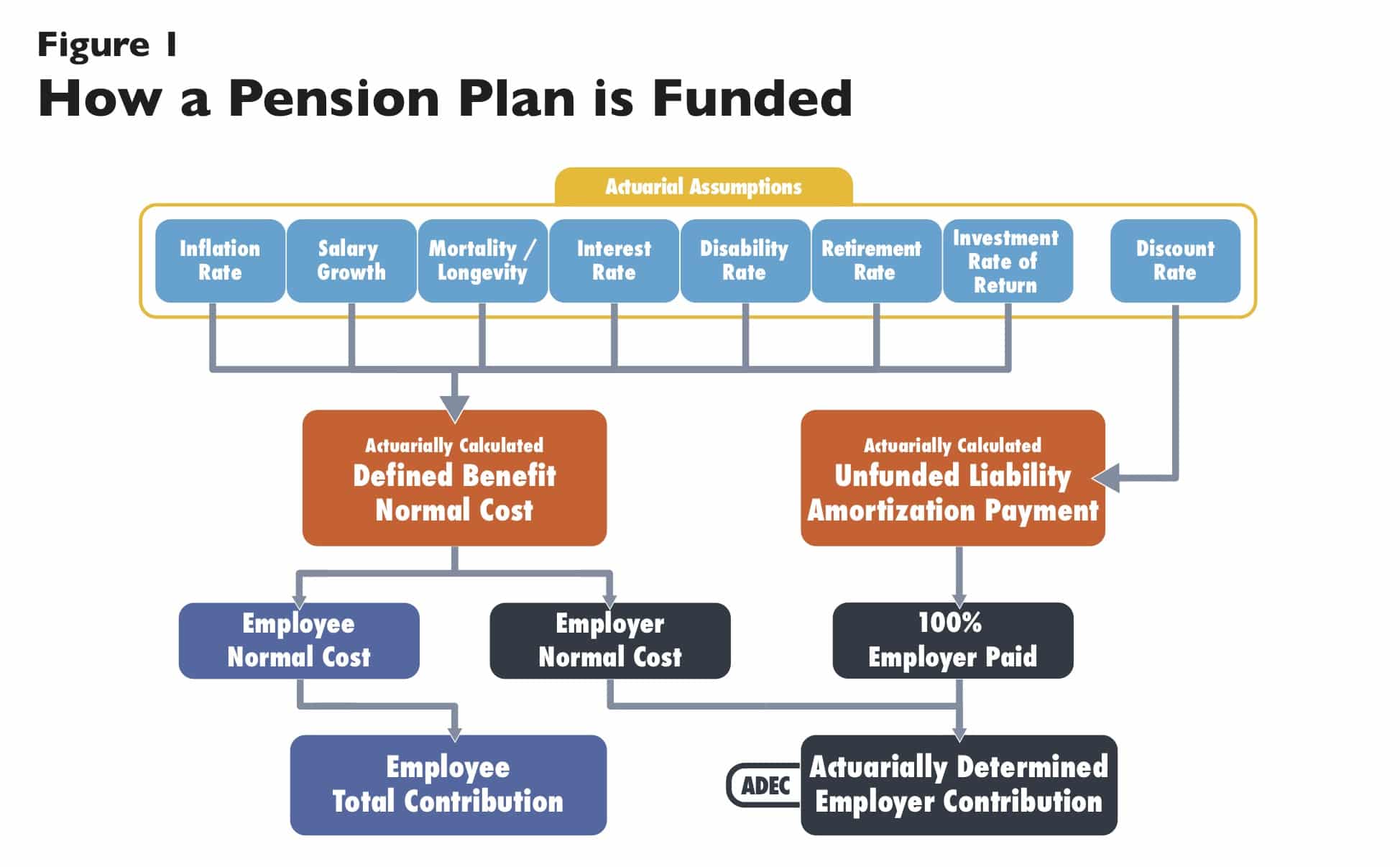

Figure 1 illustrates the typical method for determining and splitting up annual pension contributions. As a part of the pension funding equation, most public sector pension plans characterize contributions from employees as money for prefunding individual benefits only, an amount commonly known as the normal cost. In other words, any money coming from an employee is used only to pay toward their own future benefits that they’ve earned during that period. Employer contributions are then used to cover what is left of the normal cost. In a fully funded pension system, the normal cost contributions from employers and employees are all that would be required, but in the event that unfunded liabilities accrue over time, the employer is typically responsible for making an additional unfunded liability amortization payment over and above the normal cost contribution until the pension debt is eliminated.

Members leaving a pension, therefore, add nothing to a plan’s unfunded liabilities—by definition, since no additional pension “liability” can accrue for work not undertaken. Hence, workers leaving a pension system can in no way reduce the money available for paying off these debts. All that they take with them is the funding which would have gone towards the normal cost, which is no longer needed since the employees will stop accumulating pension benefits once they leave.

Importantly, none of those employee contributions would have been used for paying off whatever pension debt accumulated during their tenure—in most public pension plans in the U.S., paying off pension debt is the sole responsibility of the employer.

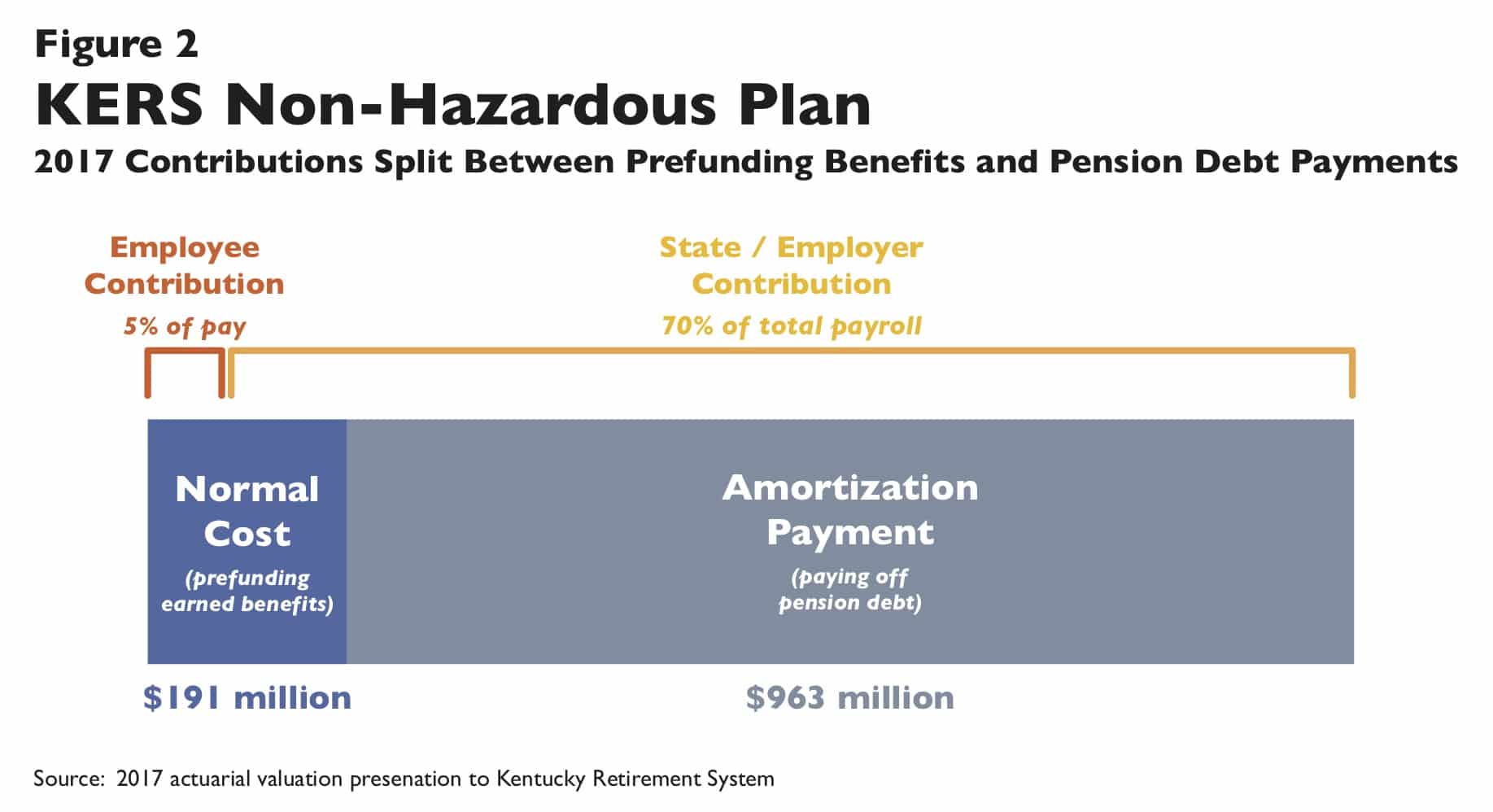

The fact that employee contributions go solely to pre-funding benefits—and not to paying down pension debt—is evident in KRS’ own actuarial reporting. Figure 2 visualizes how the KERS Non-Hazardous plan determined and split up 2017 contributions into the fund. As the figure shows, employees contributed 5 percent of their 2017 pay into the fund. Their contributions made up less than half of the 2017 normal cost. Employer contributions, which were determined by a percentage attached to the year’s total payroll, paid what remained of the normal cost and the amortization payment in its entirety.

To this point, the concern raised by KRS and the Herald-Leader article closely mirrors the oft-expressed—and often misunderstood—concern of transition costs. As the argument postulates, transitioning from a DB pension plan to a defined contribution (DC) plan would require higher required contributions from employers and possibly even remaining DB members now in order to facilitate de-risking the plan for the long-term. The increased contributions would be primarily the result of accelerated amortization schedules and adjustments towards lower returns from the transition towards less risky investment portfolios, according to this logic (which is flawed, though beyond the scope of this article). More to the point, similar to the WKU privatization issue, the underlying notion in the transition cost debate is that sending new hires into a different retirement plan will harm the solvency of the legacy plan.

To the contrary, pre-funded DB pensions are not a Ponzi scheme that relies on funds from new entrants to sustain the benefits for current members. Closing an unsustainable DB plan to new entrants and putting all new employees into some new type of less financially risky retirement plan—whether that be a better designed DB pension plan, a hybrid plan, a defined-contribution plan, or a cash balance plan—can be an effective way to avoid growing pension debts going forward, and in no way inherently increases the amount needed to pay off unfunded obligations. In both situations, the employee is in no way responsible or attached to the pension debt that may have accumulated either from underpayments or missed assumptions—pension debt remains the obligation of the employer no matter whether or not a new plan is offered to new hires.

One point of confusion on this subject may come from the understanding that a reduced payroll means that KRS will receive lower contributions. Since contributions are determined by KRS for employers like WKU as a percentage of payroll, a lower payroll caused by privatizing a group of employees would result in lower contributions flowing into the pension fund.

However, the reduction will be the loss of normal cost contributions for pre-funding future benefits going forward—and nothing more since the debt payment would remain an employer responsibility—so KRS’ loss in incoming funds will be offset equally by the reduction in promised future benefits. In clearer terms, WKU’s action to move employees to a private contractor is cost neutral to KRS. If anything, the move will reduce costs for the commonwealth and all participating employers in the long-term, since there are fewer promised retirement benefits that could accumulate liabilities for KRS in the future.

Perhaps the concern is that KRS will need to ask for a higher employer contribution calculated as a percentage of payroll, but this would be an increase in percentage only and not a nominal increase in the dollar amount. Since the actual payroll number is reduced with departing workers, and the amortization—or debt—payments must remain the same, KRS will need to raise the percentage it is requiring from employers like WKU. As far as employers are concerned, however, the nominal amount they are contributing to pay off pension debts should remain steady (assuming no other changes to actuarial assumptions and the like).

The above then raises the question, “If WKU’s move to privatize a group of its workers has no effect on KRS’ ability to pay off the plan’s pension debt, why is KRS taking exception to the university’s actions?” Perhaps only the retirement system’s officials can answer, but it would not be unreasonable to speculate that they may see the growing privatization trend—and consequently shrinking membership—as a threat in and of itself.

WKU’s bout with KRS on this issue and the cited Herald-Leader article highlight a common misconception associated with pension funding policy. It is important to understand that pension plans do not require current public workers to make payments towards pension debt. Unfunded liabilities tend to be produced by insufficient contributions from employers, too-loose funding policy or missed assumptions and are not the responsibility of the employee. It’s also critical to understand that workers leaving an underfunded pension plan in no way inhibit the employer’s ability to reach full funding. It is, therefore, inaccurate to apply blame on public employers like WKU or their privatized workers for the KRS’ ongoing problems.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.