In recent years, many politicians advocating for improvements to rail safety have called for new industry regulations. These calls reached new heights following the Feb. 2023 freight train derailment and emergency response in East Palestine, Ohio. Members of Congress reacted with legislation: the Railway Safety Act in the Senate and the Railroad Safety Enhancement Act in the House of Representatives.

While introduced ostensibly in response to the East Palestine derailment, both bills would impose a variety of prescriptive regulatory mandates that have no plausible connection to the accident. Most egregious are the bills’ provisions that would mandate two-person train crews, even though the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that crew-handling played no role in the East Palestine derailment, and the train in question had three crewmembers on board.

But the underlying flaw of both bills is they presume public regulation is automatically a solution to rail safety challenges and ignore the important roles of private and consensus standards in delivering safety improvements.

Background on Standards and Federal Regulation

Technical standards are widely used by industries to establish uniform requirements for the development, testing, production, and use of goods and services. The purpose of standards is twofold: first, to ensure all parties understand the features of a product or service that meet a given standard; and second, to prevent the adulteration or debasement of the product or service subject to the standard. In the parlance of economics, standards are designed to reduce transaction costs by providing would-be buyers with sufficient information to judge the quality of the product or service being offered for sale.

Standards are produced by a variety of organizations. These entities may be international standards societies such as the International Organization for Standardization. They may be cross-industry national consensus standards organizations, such as the American National Standards Institute. They may be industry-specific consensus standards groups, such as SAE International for the automotive industry. Or they may be industry-specific private standards bodies, often trade associations that represent companies from those industries.

Regulatory agencies frequently make use of technical standards. In the United States, regulatory agencies must provide notice to the public of the specific requirements that their regulations impose. Instead of reproducing standards in whole or in part in the Code of Federal Regulations, regulations will often just cite nongovernmental standards, which is known as “incorporation by reference.” In practice, this means the cited nongovernmental technical standards carry the force of the law and compliance is mandatory.

Congress and the executive branch have established policies governing the use of technical standards in regulation. These policies reflect the recognition that technical expertise largely resides outside of government, and regulators should seek to leverage nongovernmental knowledge whenever possible. As part of the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 1995, Congress required regulatory agencies to generally “use technical standards that are developed or adopted by voluntary consensus standards bodies, using such technical standards as a means to carry out policy objectives or activities determined by the agencies and departments.”

To implement this statutory mandate, the White House Office of Management and Budget issued Circular A-119 and further defined the standards-related obligations of federal agencies. Circular A-119 states that “this policy establishes a preference for the use of voluntary consensus standards in lieu of government-unique standards” and that agencies “should give preference to performance standards” that specify desired outcomes rather than prescriptive standards that specify a particular means of compliance.

The Use of Standards in Railroad Regulation

For the U.S. rail industry, the principal standards-developing organization is the Association of American Railroads (AAR). The AAR is the industry’s trade association and produces the Manual of Standards and Recommended Practices (MSRP). The current edition of the AAR MSRP currently contains nearly 750 specifications, recommended practices, and standards (for simplicity, I’ll refer to these collectively as “standards”), which are grouped into more than two dozen subject-specific sections.

Section volumes are revised approximately every two years. Between revisions, standards may be updated and issued as AAR Circular Letters. Of those nearly 750 standards contained in the AAR MSRP, roughly 20% have accompanying AAR Circular updates pending inclusion in the next section volume revision.

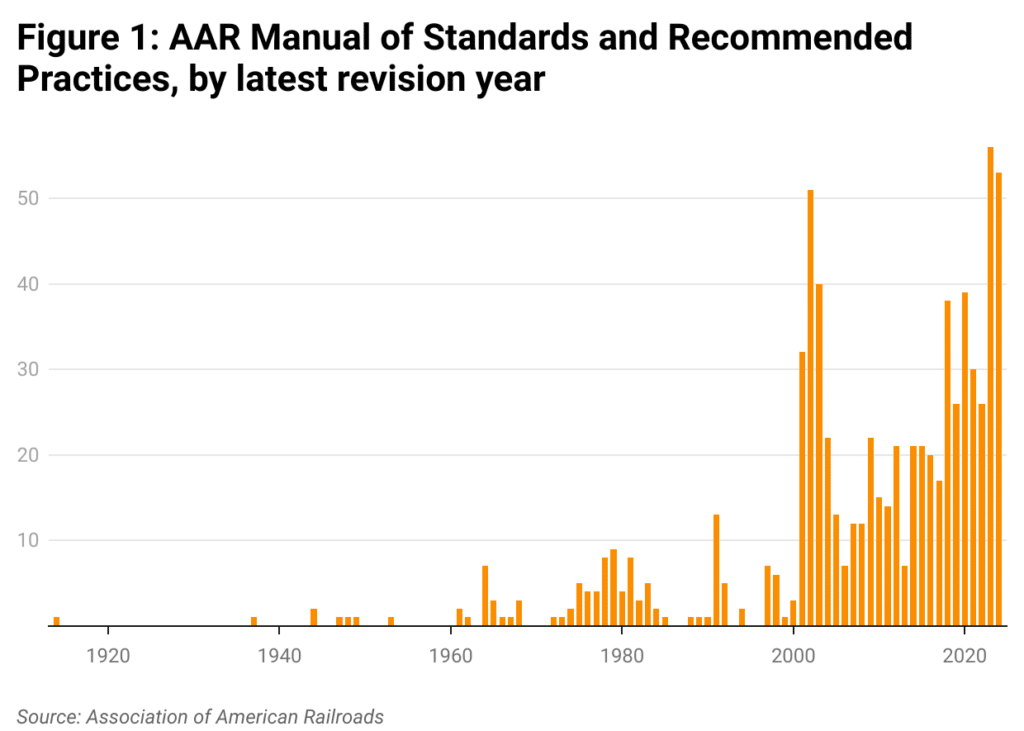

The continual evolution of standards through the technical committee process has resulted in most AAR MSRP standards being revised since 2000, with the median standard revision year being 2012. A visual depiction of AAR MSRP standards by revision year is produced in Figure 1.

Most of the AAR MSRP standards are not incorporated into regulations promulgated by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), the U.S. national rail safety regulator. As such, compliance with most elements of the AAR MSRP is enforced via private contract, and the AAR maintains a large inspection program to support adherence to its standards.

However, the FRA does make use of more than 150 nongovernmental standards published by the AAR and other organizations. A review of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Standards Incorporated by Reference (SIBR) Database finds that the median standard edition year incorporated into FRA regulations is 2001. Figure 2 provides a visual depiction of the standards incorporated by reference into FRA regulations by standard edition year, according to the SIBR Database.

The Conformity Gap Between Railroad Standards and Regulations

Despite best agency efforts to ensure their regulations reflect modern best practices from standards-developing organizations, they often fall far short of the conformity that Congress desires. To incorporate a new standard in regulation or update a regulation to reflect a revised standard, agencies must follow specific procedures that necessarily make this a time- and resource-intensive endeavor.

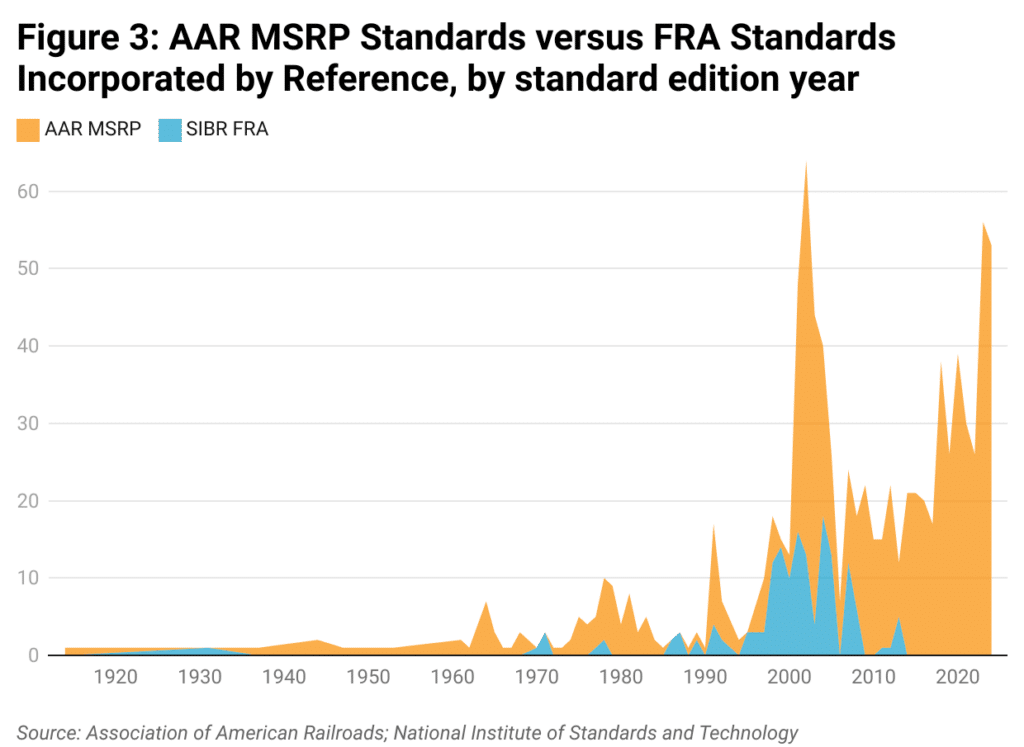

One practical result is that regulations often reference outdated standards. Figure 3 compares the standard edition years of AAR MSRP standards with standards incorporated by reference in FRA regulations. While this is not quite a like-for-like comparison, it shows a roughly 10-year lag between the latest railroad industry standards and railroad safety regulations.

To attempt to address this gap, agencies sometimes have mechanisms that trigger accelerated proceedings to update regulations after revised standards are published. For example, the FRA has a number of regulations on train brakes and test procedures. If a brake standard from the AAR MSRP is revised and the version incorporated by regulation becomes outdated, the process for updating the regulation to reflect the newly revised standards is as follows (49 C.F.R. § 232.307):

- The AAR or other railroad industry representative must submit a request for modification to the Federal Railroad Administration that includes the specific regulation and standard at issue, the requested text of the modification, appropriate data and/or analysis supporting the modification, and a statement affirming the rail industry has served a copy of the request to affected employees.

- Upon receipt of the request for modification, the FRA will publish a notice in the Federal Register containing the request and opening a 60-day public comment period.

- If the FRA does not object to the request for modification and receives no adverse public comments, the requested modification will become effective 15 days after the close of the public comment period.

- If the FRA does object to the request for modification or receives any adverse public comments, FRA will either approve with conditions or deny the request “normally within 90 days” of receipt. However, if a decision by the FRA is not made within 90 days, the request for modification remains pending until the FRA makes a decision. In other words, the 90-day review clock is aspirational rather than binding.

- If a request for modification is denied, the railroad industry may petition for reconsideration, which starts this process over.

However, most FRA regulations incorporating nongovernmental standards do not contain update trigger mechanisms, so any updates will require conventional rulemaking proceedings. This gives agencies more discretion over any potential regulatory changes and increases the length of time to complete a change. Given this cumbersome and uncertain process to address outdated standards that have already been referenced in regulation, the persistent conformity gap between standards and regulations should not be surprising.

Implications for Policymakers

Policymakers’ support for improved rail safety is admirable. However, many have expressed the belief that safety is primarily driven by federal safety regulation while ignoring the real-world incentives and behavior of railroads. This is mistaken in two important ways.

First, economists have found that the dramatic improvements in rail safety since 1980 are almost entirely attributable to the improving financial health of the railroad industry. A 2016 study published in the Review of Industrial Organization estimated that approximately 90% of the reduction in the train accident rate between 1980 and 2013 was attributable to the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, which eliminated many economic regulations on the industry.

Railroads have a strong private incentive to minimize accidents that damage their property, injure their employees, and disrupt their operations. The Staggers Act freed railroads from the most onerous economic regulations that nearly bankrupted the entire sector by the end of the 1970s. This economic decline coincided with a disturbing rise in accidents. Following enactment, railroads were able to again earn sufficient returns to bring their deteriorating infrastructure and equipment back to a state of good repair and optimize their operations to reduce hazardous railcar switching.

Second, railroads’ own industry standards often exceed the requirements imposed by federal regulation. For instance, the AAR’s definition of “key train” is roughly analogous to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration’s (PHMSA) regulatory definition of “high-hazard flammable train.” This regulation was promulgated in 2015 and mandates special operating requirements for trains that carry large volumes of certain hazardous materials.

Yet the AAR’s key train definition revision that was published in 2013 applies to a broader set of trains than the corresponding federal rule. Further, PHMSA’s 2015 high-hazard flammable train regulation was prompted by a National Transportation Safety Board recommendation that regulators adopt the key train operating practices established by the AAR.

In addition, safety regulations often reflect outdated industry standards and are overly focused on rote compliance rather than safety outcomes. In the aforementioned 2016 study on the regulatory determinants of rail safety, the authors note that railroad safety regulations may do less to improve safety than their proponents assume. Specifically, they caution that prescriptive safety regulations, as opposed to performance-based regulations, may be counterproductive. They conclude:

Safety regulation can have perverse effects. When safety regulation takes the form of detailed, mandated actions, it encourages firms to focus on complying with the mandates or negotiating exceptions rather than creatively using their own expertise to manage and reduce risks… .

In short, by diverting attention from safety outcomes to compliance, design standards can make railroads less safe than they would otherwise be. In the extreme case, this might mean that safety regulation reduces safety. A more likely scenario is that marginal additions to safety regulation reduce safety even if the net effect of all safety regulation is still positive.

Policymakers who truly wish to advance rail safety must take care to avoid negative impacts arising from the blunt tool of regulation. They should appreciate that most advances in safety occur voluntarily within private industry, where economic incentives are powerful safety motivators. To pass the public interest test, any proposed safety regulation should address an identified market failure and avoid short-circuiting the continual evolution of safety-enhancing technologies, standards, and operating practices.