Last month, the Philadelphia City Council narrowly approved a one percent tax on new construction. Unlike other taxes in the city meant to reduce consumption and affordability—such as taxes on soda and cigarettes—the goal of this tax is to increase access to affordable housing.

The new tax is levied on all construction that requires a permit and is for human occupancy. It is projected to bring in $23 million annually for the city’s Housing Trust Fund. The city council approved the tax as part of a Putting Philadelphians First legislative package, which also grants zoning bonuses to developers. If builders set aside 10 percent of new units at affordable rates, they can be eligible for additional units, gross floor area, or building height.

Requiring developers to fund affordable housing is not unique to Philadelphia. In metropolitan areas across the United States, housing shortages fueled by population growth, new jobs, and rising property values have prompted inclusionary zoning laws that require developers to sell or rent out a portion of new units at a below market rate.

The housing crisis in Philadelphia is different from the growing pains experienced in booming metropolises like the Bay Area’s Silicon Valley. Rent in Philadelphia is low compared to other cities but high when considered in the context of area income.

The poverty rate in Philadelphia is the highest of the top 10 major U.S. cities, with 25.7 percent of the population living below the poverty line. As a result, a U.S. Department of Housing and Development report found that an estimated 42.4 percent of the city’s very low-income renters either spend more than half of their income on housing or live in sub-par conditions—that’s 145,000 “worst case needs” renters.

While the city offers a 10-year tax abatement on 100 percent of additional property taxes from new construction or real estate improvements, this policy has failed to adequately address the housing problems facing low-income Philadelphians. The benefits of the abatement have been concentrated in the greater Central City area and high-value properties. In fact, new high-value construction is replacing inexpensive housing in the city—between 2004 and 2014, the city lost one in five units priced at $750 or less a month.

The construction tax is seen by many as a way to right the wrongs of the abatement. As Maria Gonzalez, president of the Hispanic Association of Contractors and Enterprises and board president of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations, wrote in an op-ed: “The Construction Impact Tax and the affordable homes it would fund would be a first start in returning something to low- and moderate-income Philadelphians, who have subsidized the building of high-end, market-rate homes and apartments.”

Yet it is not clear that revenue from the new construction tax will reach low-income Philadelphians. The legislative package is intended to both address “a decline in affordable housing stock and stubborn barriers to homeownership for middle-income Philadelphians.” Under this legislation, revenue from the tax would be placed into a new sub-fund of the Housing Trust Fund for housing projects that benefit Philadelphians making no more than 120 percent of the area median income—meaning a family of four earning up to $105,000 a year is eligible for assistance.

Between 2006 and 2017, the Housing Trust Fund only built or rehabilitated 1,572 homes. Further, in a report conducted by the Housing Alliance of Philadelphia, they projected that a $25 million investment in the Housing Trust Fund could only result in the renovation of 1,700 rental homes.

Considering that the new construction tax is only bringing in $23 million, some of which will be spent on closing cost assistance for middle-income Philadelphians and other programs, it is unlikely that the tax will make a dent in the housing shortage. The potential new construction seems especially ineffective considering Philadelphia is estimated to need 38,000 new apartments by 2030 and is only on track to build 32,930.

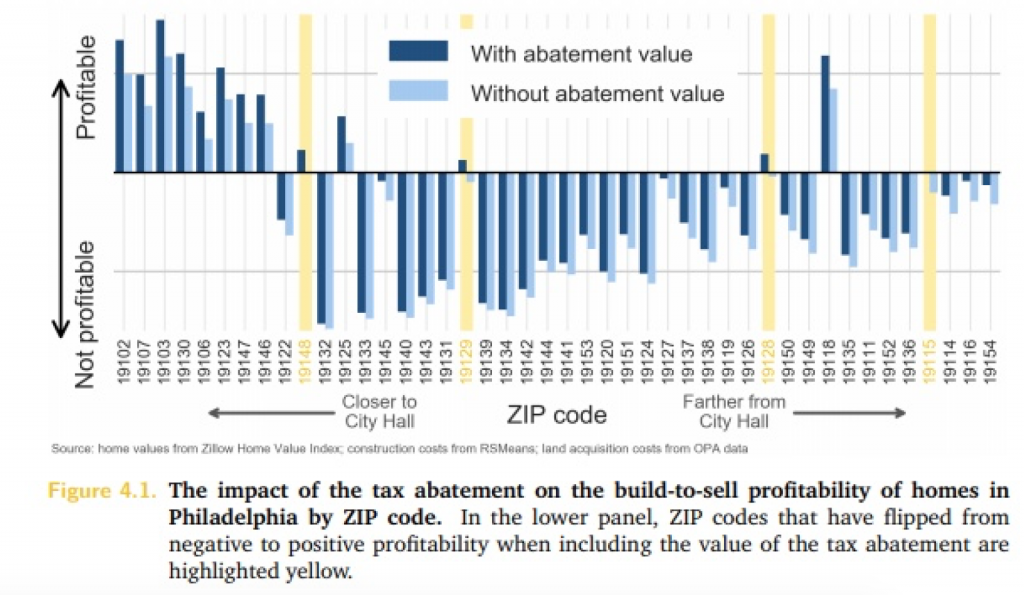

The Housing Trust Fund is not the answer to the city’s housing affordability problems. Instead, the city needs to address why the abatement has only been used in certain neighborhoods. A report conducted by the Office of the Controller found that only a handful of Philadelphia zip codes are currently profitable for development because of high construction costs but relatively low sale values and rents. As shown in the graph below, the tax abatement is not enough to make development in much of the city profitable.

For building a typical single-family row house, construction costs in Philadelphia are the fifth highest of any U.S. city and are 24 percent above the national average. Much of this is driven by high union worker costs which are 18 percent higher than the national average. Philadelphia was also ranked the fifth most restrictive metro area to build new apartments in with lengthy review processes and burdensome zoning.

While the construction tax will benefit a few lucky Philadelphians, who are able to move into a new apartment or receive down payment assistance, it does so at the expense of all other potential homebuyers and renters who will subsidize the move. The best way to address the housing crisis in Philadelphia is to lower costs by reducing barriers to new construction.

The city council plans to reform the building code to reduce construction costs over the next year. Yet these changes should have been the priority. Luckily, Mayor Jim Kenney has expressed opposition to the construction tax. A mayoral veto might force the city council to address the affordable housing crisis by lowering costs, rather than raising them.