Home to the first skyscraper and advanced data science, Chicago has earned its reputation as one of the most innovative and forward-looking hubs in the world. But the same cannot be said for the city’s stewardship of its pension systems for public workers. And one need not look too far for evidence.

The most recent data shows Chicago is grappling with more pension debt as a percentage of its overall government revenue than any other American city (see 2015 estimates from Moody’s Investors Service). Dallas and Phoenix round out the top three of Moody’s list of cities that are most fiscally stressed by pension debt. The situation is so acute that In 2015, Moody’s slashed the credit rating on Chicago’s general obligation debt from “Baa2” to junk “Ba1” status, citing “highly elevated unfunded pension liabilities”, with another downgrade in sight.

Municipal credit ratings matter because they typically influence the debt costs borne by city taxpayers. When credit ratings fall, municipalities and their taxpayer base typically pay higher interest rates to new municipal bond buyers, compensating them for the marginal investment risks.

Compounding the problem is that as Chicago’s pension debt payments rise there is a simultaneous crowding out of funds that would otherwise be spent on education, parks, or public safety. Even worse, Chicago is experiencing a net out-migration of residents for a second year in a row, depriving the city of additional revenue.

Chicago has six pension plans for its public sector workers:

- Chicago Public School Teachers’ Pension and Retirement Fund (CTPF),

- Policemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago (PABF),

- Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago (FABF),

- Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago (MEABF),

- Laborers’ and Retirement Board Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago (LABF), and

- The Retirement Plan for Chicago Transit Authority Employees (CTA)

As shown in Figure 1, Chicago faces a combined $45.5 billion in unfunded liabilities for these six pension funds, as of fiscal year end 2015 data (according to the plans’ GASB 68 reports).

| Figure 1: Chicago Pension Plan Solvency Overview | ||||

| Plan | Actuarial Liability | Market Assets | Unfunded Liability | Funded Ratio |

| MEABF | $23.36 billion | $4.74 billion | $18.62 billion | 20.3% |

| CTPF | $20.71 billion | $10.69 billion | $10.02 billion | 51.6% |

| PABF | $12.03 billion | $3.06 billion | $8.97 billion | 25.4% |

| FABF | $4.83 billion | $1.05 billion | $3.78 billion | 21.7% |

| LABF | $3.71 billion | $1.24 billion | $2.47 billion | 33.4% |

| CTA | $3.35 billion | $1.74 billion | $1.61 billion | 52.0% |

| Total | $68.00 billion | $22.52 billion | $45.48 billion | 33.1% |

Source: MEABF, CTPF, PABF, FABF, LABF, and CTA 2015 Actuarial Valuation reports, CAFRs, and GASB Statements. Unfunded liability shown is net pension liability. Market assets shown are fiduciary net position/net assets. Results for all plans, except CTPF and CTA, are based on “blended discount rate. ” Data for all plans – except CTPF that shows fiscal year ending June 30, 2015 – represents fiscal year ending December 31, 2015. Figures are rounde

|

||||

And while this is a massive problem, reality is probably much worse. That’s because these amounts are likely underreporting the true value of unfunded pension liabilities because they are based on plans’ current assumptions — many of which are optimistic at best (more on this point later).

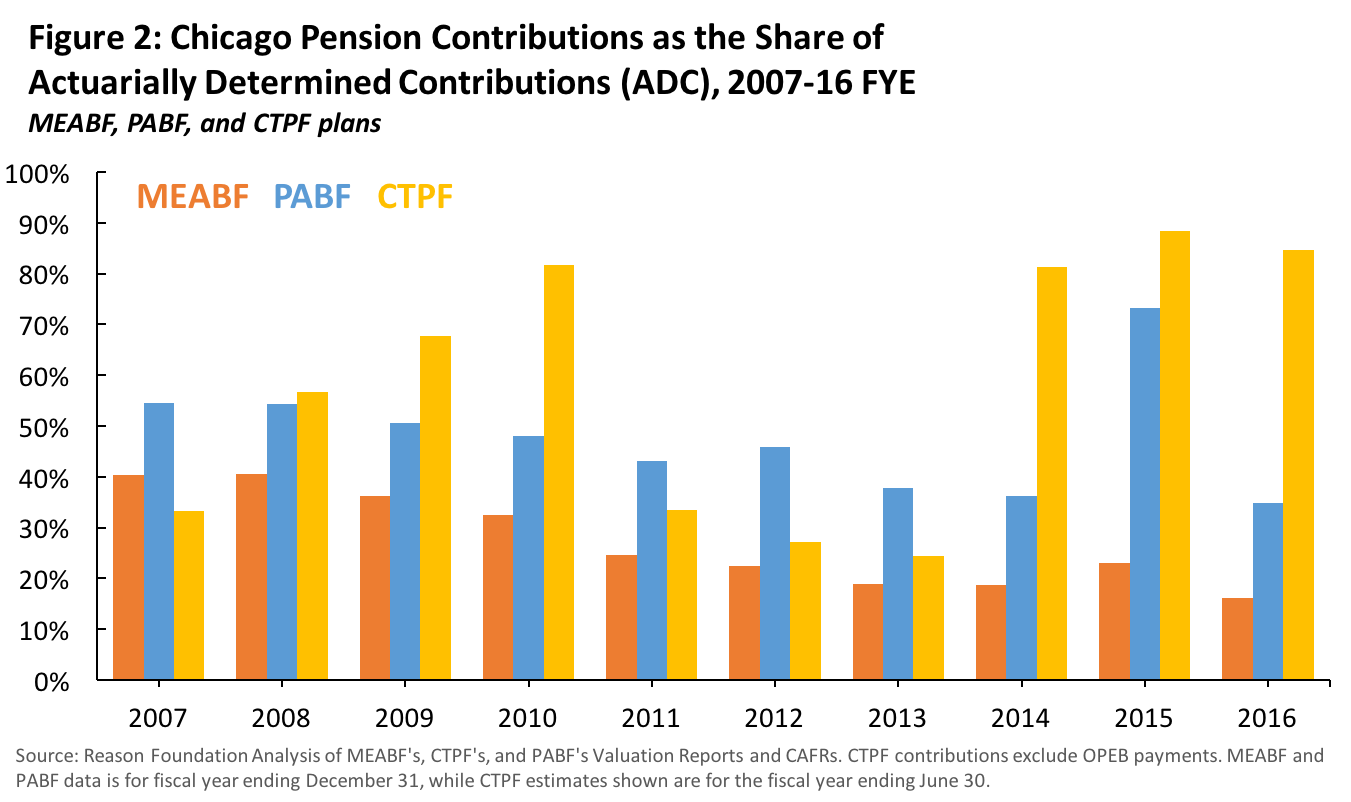

Chicago’s ballooning pension debt is not much of a surprise when looking into the history of its pension mismanagement. Left to their own devices, the city’s pension funds have been continuously kicking the unfunded liability can down the road, often coming short of the actuarially prescribed contribution rates. Figure 2 displays the contribution shortfalls by the three major pension plans over the last decade.

In fact, since at least 2006, Chicago has never come close to fully funding its annual pension obligations of MEABF, something also noted recently by my colleague Eric Boehm. The city’s second largest pension plan (CTPF), in most years, has seen less than two-thirds of the money it needed to maintain solvency (see Figure 2 below). Worse, since 1996 Chicago Public Schools (primary employer in CTPF) has taken a perverse liking to so-called pension “holidays” — diverting actuarially required funds meant to cover normal cost and amortization payments to pay for teachers’ salaries instead.

On average, since 2007, Chicago has been contributing 48% and 58% of the actuarially determined employer contribution (ADEC) to its police and teachers plans, and just 27% to its municipal plan. Needless to say, the billions of dollars of required contributions not made continued to add to Chicago’s already colossal pension debt every single year.

As outlined in a 2016 Reason Foundation study, inadequate employer contributions and unmet assumptions are two of the main drivers behind the growth in unfunded liabilities among public sector pension plans around the country.

Unfortunately, Chicago’s plans have struggled to meet their own return expectations so far. For example, the past decade investment returns of teachers, municipal, and police plans averaged out to 5.3%, 4.5%, and 4.3%, respectively. This is far below the rosy assumed returns currently used by the plans that range from 7.5% to as high as 8.25% (CTA).

At the same time, Chicago’s plans use these unrealistic expected returns to discount the value of promised pension benefits. Using discount rates that are too high undervalues the total amount of outstanding pension obligations or liabilities. Figure 3 demonstrates how much worse the numbers are if each plan were to use a more realistic 3.7% discount rate, which was originally applied by MEABF in its 2015 GASB report, to value its liabilities.

| Figure 3: Chicago Pension Plan Solvency Overview Using 3.7% Discount Rate | ||||

| Plan | Actuarial Liability | Market Assets | Unfunded Liability | Funded Ratio |

| MEABF | $23.36 billion | $4.74 billion | $18.62 billion | 20.3% |

| CTPF | $34.08 billion | $10.69 billion | $23.39 billion | 31.4% |

| PABF | $18.24 billion | $3.06 billion | $15.18 billion | 16.8% |

| FABF | $7.39 billion | $1.05 billion | $6.35 billion | 14.1% |

| LABF | $3.87 billion | $1.24 billion | $2.64 billion | 32.0% |

| CTA | $5.86 billion | $1.74 billion | $4.11 billion | 29.8% |

| Total | $92.80 billion | $22.52 billion | $70.29 billion | 24.3% |

Source: MEABF, CTPF, PABF, FABF, LABF, and CTA 2015 Actuarial Valuation reports, CAFRs, and GASB Statements. Unfunded liability shown is net pension liability. Market assets shown are fiduciary net position/net assets. *Data for all plans – except CTPF that shows fiscal year ending June 30, 2015 – represents fiscal year ending December 31, 2015. Figures are rounded. |

||||

One needs accurate scales to start losing weight. Discounting reported 2015 liabilities by 3.7% brings the city’s combined pension debt from $45.5 billion up to $70.3 billion. Potentially exceeding $90 billion, according to the Hoover Institution.

The current accounting gimmick used by Chicago’s plans to understate the value of liabilities is not limited to the Windy City, but it is nonetheless a contributing factor to the ongoing woes of Chicago.

But that’s not it. On top of inadequate assumptions and insufficient payments, city retirement plans also have flawed funding policies in place. All of the city’s funds, except CTPF, currently use so-called open amortization method. This method essentially creates a schedule of perpetual unfunded liability payments, making it almost impossible for the debt to be ever paid off.

Even using existing actuarial assumptions, PABF is expected to run out of money as early as 2021, as reported by Chicago wire service LGIS. The MEABF and LABF plans are likely to follow in 2025 and 2027, respectively, according to the city’s projections.

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, in part due to the state legislature’s gridlock, has implemented number of new taxes to try and address this underfunding.

In 2014, Mayor Emanuel initiated the largest property tax hike the city has ever seen to fund the city’s police and fire pension plans. This new mandate is expected to generate $543 million in additional taxpayer dollars over four years. Similarly, a water and sewer tax levied in 2016 is to be phased in over four years and used to shore up the MEABF.

Originally aiming at bringing the police and fire pension plans to 90% funded status by 2040, Illinois General Assembly later moved the goal post to 2055 with the Public Act 099-0506. Under this new law, city will be making ramp contributions until the actual payments equate with ADEC estimates in the 2022 fiscal year.

Overall, since the Mayor took office in 2011 the combination of initiated and planned tax increases are estimated to cost an average Chicagoan as much as $1,700 more a year when fully phased in, as reported by the Chicago Tribune.

| Figure 4: Chicago Annual Tax Increases Dedicated to City Pensions | |||

| Year | Tax | Estimated Proceeds | Beneficiary |

| 2014 | Property Tax | $318 million | PABF and FABF |

| 2015 | Reinstated Pension Levy | $250 million | CTPF |

| 2016 | Water-sewer Tax | $56 million | MEABF |

| 2016 | 911 Communications Tax | $34 million | LABF |

Source: Publicly available information from government and private resources. The tax amounts represent projected revenue for the fiscal year following the year tax was levied. The 2016 property tax increase is supposed to be phased in over 4 years, raising $318 million the first year and $543 million in total. The water-sewer tax is also planned to be phased in over 4 years, potentially generating $239 million in total tax revenue. |

|||

Furthermore, traditional debt continues to mount alongside the pension debt. For example, just last year the Chicago Public School system issued a massive municipal bond, putting city taxpayers on the hook for another $850 million in the next 30 years.

Chicago’s position is unenviable from every vantage point. Taxpayers feel the direct impact of tax increases and service-level budgetary crowd out. And the longer fiscal woes drag on, employees and retirees would face a growing threat to their retirement security. The city’s economic future is undermined by the rising pension debt that will likely keep mounting until state and local policymakers implement comprehensive pension reforms. Reforms that put the city’s retirement systems on a path to long-term solvency.