The U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee introduced The American Privacy Rights Act (APRA) in April, the latest attempt to create a national framework in response to a growing number of state-level laws regulating consumer data privacy after a 2022 bill stalled before reaching a full vote. Absent action from the U.S. Congress, many states have advanced privacy initiatives, enacting bills that attempt to tackle consumer data protection in many ways.

In a nutshell, APRA introduces extensive privacy controls and allows consumers to decline consent on certain data practices, mandates clear privacy policies and compliance mechanisms for businesses, and offers consumers the right to take legal action for violations. The bill emphasizes data minimization, ensuring companies collect only necessary information, and it seeks to supersede varied state laws.

State and local governments often benefit from being more attuned to the specific needs and contexts of their communities, allowing for tailored regulations. However, the realities of 21st-century data communication add potentially challenging new dimensions to tradeoffs between state and federal regulation. State lines can be an arbitrary and costly way to regulate data. Europe, in contrast, has taken a much more centralized approach through the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation law.

While APRA aims to address the current patchwork of state privacy legislation, it is important to analyze the various state privacy laws to consider whether a top-down federal replacement of them is necessary. While existing state regulations frequently have similar elements to APRA, there are important distinctions to consider.

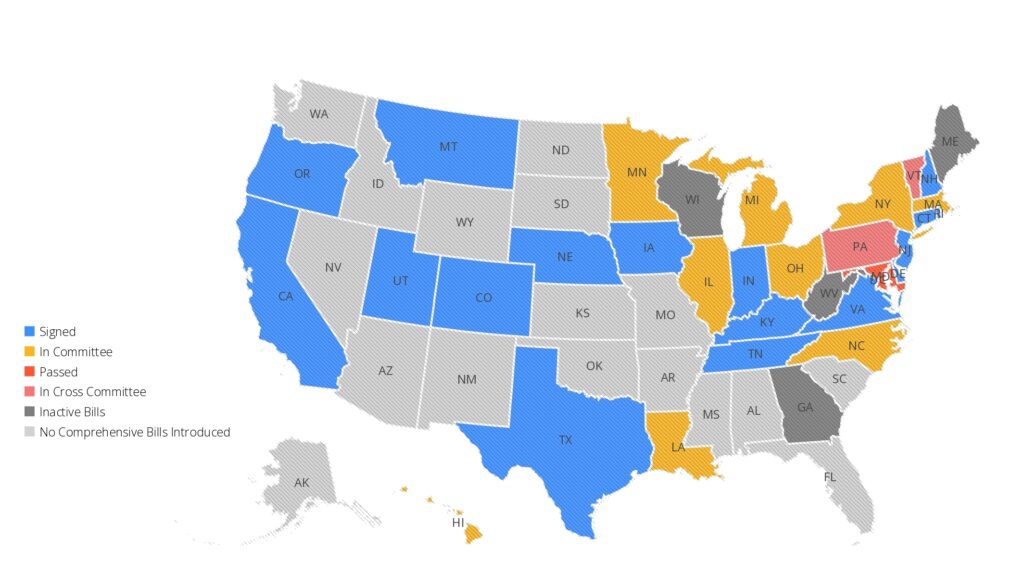

Currently, 15 states have enacted comprehensive data privacy laws (Figure 1). The accompanying map illustrates the progress of state-level legislation. In 2023 alone, eight states added consumer privacy laws to their statutes.

Figure 1. U.S. State Privacy Legislation 2024

While there are similarities among the laws, such as a mandate to use only the necessary amount of data to achieve a specified purpose and an obligation for companies to inform consumers of privacy policies, each law also possesses distinct features that require significant resources and investment to maintain compliance.

All 15 state privacy laws apply to companies that conduct business with state residents regardless of whether the businesses are headquartered within or outside the state. Exceptions to these laws typically include businesses that, for example, process data of fewer than 100,000 consumers per year and do not derive more than 50% of their revenue from selling personal data.

There are three important aspects of state privacy laws. First, they all define sensitive data, which sets the scope of regulation. Next, they define consumer rights that explain what consumers can expect from the organization when handling their data. Finally, they define business responsibilities that narrow organizational responsibilities and set expectations for data management.

Definitions of sensitive data

Currently, the laws define sensitive personal data as including information such as:

- racial or ethnic origin;

- religious beliefs;

- mental or physical health diagnosis;

- sexual orientation;

- genetic or biometric data; and

- citizenship or immigration status.

Protecting sensitive personal data is a standard practice in privacy protection and is aligned with industry best practices. Virginia and Connecticut privacy laws also define sensitive data to include data collected from a child and precise geolocation data.

California, Colorado, Virginia, and Connecticut require consent and data protection impact assessments (DPIA) for processing sensitive data so that organizations may identify and minimize the data protection risks of a project. Other states, like Utah, merely require notice and the ability to opt out of processing.

While the pursuit of consent has become a common practice, it is problematic because it often lacks genuinely informed choice, is easily manipulated, can overwhelm users, and fails to ensure that individuals fully understand or can practically manage their privacy rights.

Rights of consumers

In the context of state consumer privacy laws, individuals are granted several rights regarding the accessibility and availability of their data. These rights include the ability to:

- access the personal data that an organization holds;

- request deletion of personal data; and

- ability to obtain and reuse personal data.

Eleven states provide the right for individuals to request corrections to their data held by organizations. State consumer privacy laws primarily rely on opt-out rights—such as a right to opt out of the sale of personal data and targeted advertising, as an example. Four states (California, Virginia, Colorado, and Connecticut) provide a right to opt out of profiling, which allows consumers to prevent businesses from using their data to make certain algorithmic decisions, such as personalized marketing, credit scoring, or even behavioral predictions.

Many states require opt-in to process sensitive data and data about children. However, some states, such as Utah, have an opt-out for sensitive data instead. Each law has a timeframe for responding to a consumer rights request. This timeframe ranges from 30 to 60 days.

While these rights empower consumers to control their data, they can present problems for businesses due to the complexity and cost of implementing systems that comply with varying state laws and responding to requests for access or deletion appropriately within tight timeframes.

Business responsibilities

State consumer privacy laws impose specific responsibilities on businesses to ensure the protection and proper handling of personal data. These responsibilities include the requirement to:

- publish a privacy notice;

- have reasonable data security practices; and

- collect and use only data reasonably necessary for the identified purposes (data minimization).

Data minimization mandates that personal data not be used for new purposes without explicit consent, while data transfers require stringent processing agreements. Regulations also protect consumers from penalties when exercising their privacy rights. Virginia, Colorado, Connecticut, and New Jersey require data protection assessment when processing activities involving targeted advertising, certain forms of profiling, sensitive personal data, and the sale of personal data. The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), and the Connecticut Data Privacy Act, all target deceptive practices known as “dark patterns,” which can trick consumers into making decisions that aren’t in their best interests, such as giving more personal data than they intend to.

State attorneys general are usually responsible for enforcing these regulations. An exception is California, which established the California Privacy Protection Agency. Most laws have no private right of action, except in California, which has a limited private right of action for violations involving a data breach. A private right of action allows individuals or entities to file lawsuits seeking damages or other remedies directly, without relying solely on government enforcement agencies. Private rights of action are crucial in privacy regulation because they empower individuals to enforce privacy laws directly, enhancing accountability and effectiveness by allowing judicial processes to refine the application of these laws in line with evolving social and technological contexts. This approach not only upholds the common law traditions of privacy rights in the U.S. but also ensures that privacy laws remain dynamic and responsive to public needs and expectations.

The variations between state privacy laws have led to federal legislative efforts representing a more uniform regulatory approach, such as the one proposed in the APRA. Before any federal legislation is finalized, the nuances of the state laws reviewed here should be considered and their impact on consumer experience and corporate outcomes should be carefully evaluated.