In April, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed a bill that, among other things, grants the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board (NMERB) a permanent contribution boost and changes the benefit accrual formula for active employees. While commendable, these positive steps fall short of meaningfully addressing NMERB’s longer-term solvency concerns.

New Mexico legislators just passed House Bill 360 —originally mandating state and local governments increase their contributions into NMERB by 300 basis points— that in its final version mandates government employers to increase NMERB contributions from 13.9 percent to 14.15 percent (up by 25 basis points) effective July 1, 2019.

“It was a collaborative process… [HB 360] Is a major step forward in ensuring the long-term fiscal strength of the educational retirement fund,” said Mary Lou Cameron, MMERB’s chair. According to pension officials the original bill would have helped the 52 percent-funded NMERB (using GASB standards) achieve full funding in 30 years. Per the bill’s amended language, however, NMERB would be expected to reach full funding in 44 years instead.

In addition, the new pension policy would initiate a tiered retirement multiplier for new public employees to help smooth out pension benefit accruals and nudge them toward longer careers. Defined Benefit (DB) pensions for public workers are generally calculated as:

Benefit multiplier* years of service* final average salary.

Under a single multiplier (NMERB currently uses 2.35 percent) most of the benefits accrue near the end of a public career. A tiered multiplier, however, assumes a gradual increase in the rate of benefit accruals over time, encouraging some to postpone their retirements until reaching the next or the maximum multiplier threshold (see graph below).

Table 1: New Tiered Benefit Multiplier

| Years of Service | Multiplier |

| 10 or less | 1.35% |

| 10.25 – 20 | 2.35% |

| 20.25 – 30 | 3.35% |

| 30.25 plus | 2.40% |

Jan Goodwin, NMERB’s executive director, thinks this change will slow down the accrual rate of promised pension benefits for future educational workers until they surpass 20 years of service. By extension, this could also potentially reduce future actuarial liabilities.

Legislators also implemented a measure to require all retired members who have returned to employment—as well as their employers—to start chipping into the NMERB fund as would be required if the member were non-retired.

Despite the positive steps, however, Moody’s Investor Service analysts decided to keep the state’s credit rating untouched—following two downgrades since 2016—explaining that the pension reforms did not increase contributions enough to reduce New Mexico’s unfunded financial liabilities (i.e. pensions and other post-employment benefits). In fact, as a result of the amended bill, there are only going to be additional contributions each year in the single-to-low-double digit millions, which are nowhere near the dollar amounts needed to cover the unfunded portion of the NMERB liabilities.

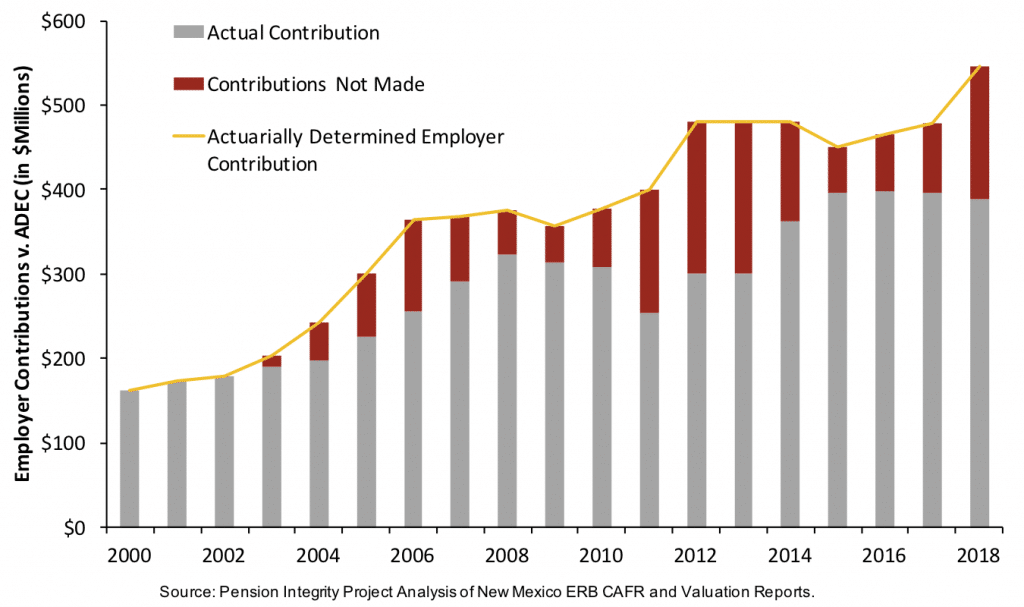

As the Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation continues to emphasize: insufficient contributions are one of the key culprits in defined benefit pension underfunding. New Mexico ERB, as with many other plans, has not been consistent in footing its pension bills in full over the past 15 years (see graph below).

Figure 1: New Mexico ERB Required vs. Actual Contributions

In fact, New Mexico contributed only 81.3 percent, on average, of the Actuarially Determined Employer Contribution (ADEC) into NMERB from 2000 to 2018. Last year alone, the state came short of the $546.6 million required contribution and paid only 71 percent of the ADEC, which alone added more than $150 million to existing unfunded liabilities.

And given NMERB’s insufficient contribution history, more significant contribution increases would need to be initiated in future, compared to what the new policy mandates, in order to close the funding gap that escalated to $11.9 billion (GASB standards) last year.

Due to NMERB’s critical role in providing retirement to 109,000 educational workers and retirees, state legislators ought to consider making a long-term contribution commitment that would better secure these funds. One way to do this would be to scrap the current practice of setting annual contribution rates in the statute. As it stands, the statutory contribution approach has an inherent risk of delaying decision-making regarding contribution increases for far too long (or never) because of the nature of the political process. In short, politicizing pension contribution rates is a bad funding policy approach, often leaving public pensions cash-strapped.

Instead, New Mexico legislators should require employers to cover 100 percent of the ADEC contribution each year going forward. The downside of this type of policy would be a reduction in year-to-year budget predictability, but the benefit would be a retirement system that is far less likely to veer off into long periods of underfunding.

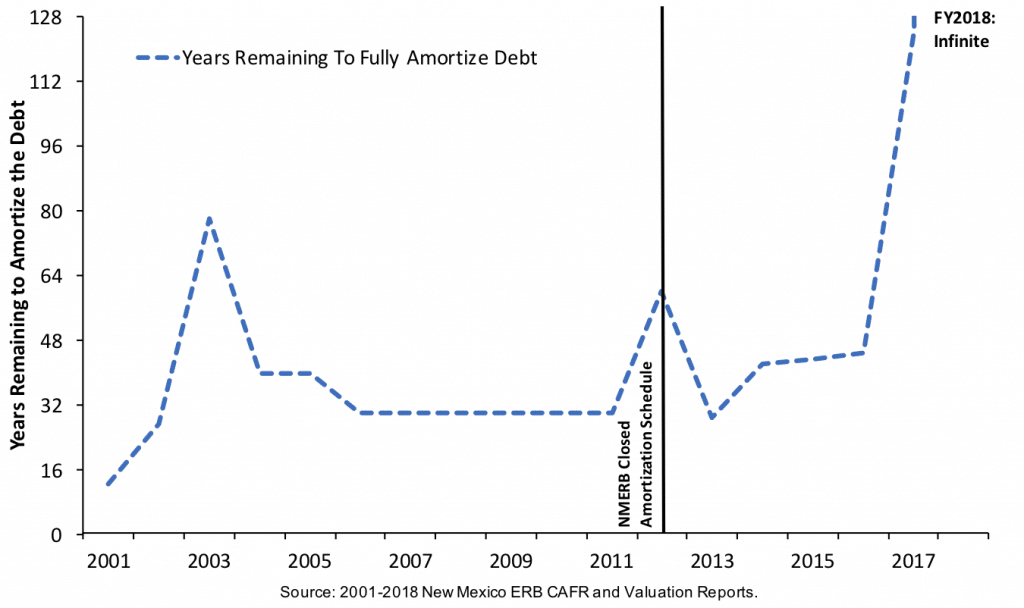

However, there is a catch. As practice shows, even paying the full ADEC might not be enough to actually reduce unfunded pension liabilities in the long-run, as Moody’s alluded to in its comments. Until 2012 NMERB re-amortized its pension debt each year over 30 years. Similar to annually re-financing a mortgage, this method nearly guarantees that the debt will never be paid off. NMERB did set a fixed end date for its debt amortization in 2012, but statutorily-set contributions were nowhere near the amounts needed to make good on this schedule. Not surprisingly, last year the amortization period reached an “infinite” number of years (see graph below).

Figure 2: Years Remaining to Fully Amortize New Mexico ERB’s Unfunded Liability

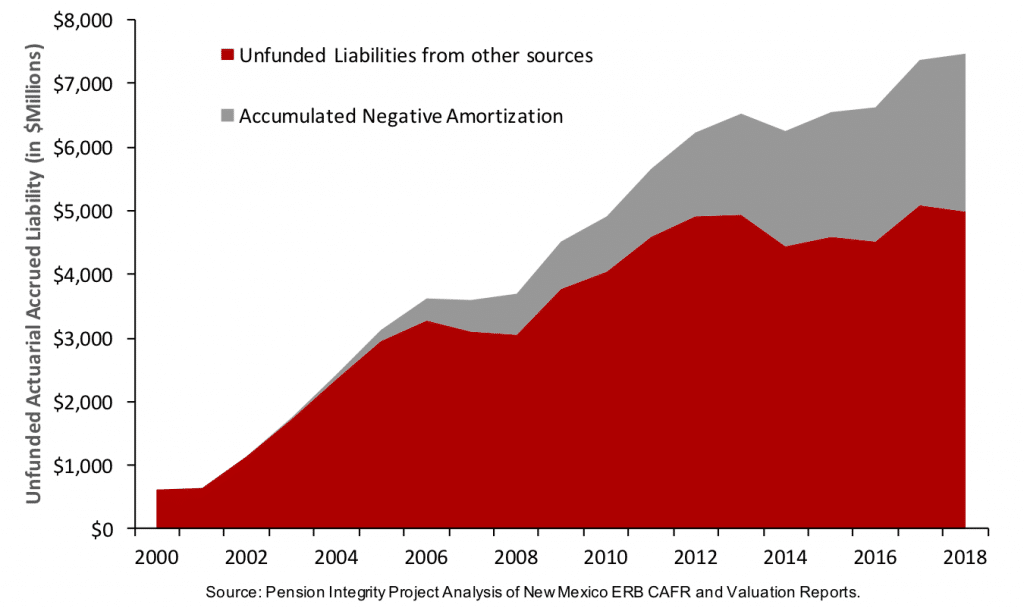

To illustrate the negative effects of insufficient contributions and poor amortization policy, over the last 16 years, ERB’s annual contributions were even below the annual interest accrued on the existing debt (a trend known as negative amortization). Negative amortization alone has added around $2.49 billion to the pension plan’s debt since 2000 (see graph below).

Figure 3: Negative Amortization as a Share of New Mexico ERB’s Unfunded Liability

As rightly outlined by Heather Gillers in a recent Wall Street Journal piece, while the 2007-08 financial crisis left many states and localities grappling with lower tax revenues and increased demand for government services, even a decade-long bull market did not alleviate public pension funding concerns. Despite its recent efforts at pension reform, New Mexico will likely continue to struggle with these same issues.

It is yet to be seen how NMERB’s new multiplier will actually affect retention and retirement rates, as well as the growth of actuarial liabilities going forward. And the increase in the state’s contributions into the system, while a positive step, will likely not be enough to stop the continued growth of pension debt. Quite often such superficial, yet positive, reform steps can be misinterpreted (or proactively portrayed) as solving the full problem — giving legislators a false sense that the reforms are more impactful than they really are and potentially stalling momentum for the additional reforms needed to tackle the risks that drove the problems in the first place.

One thing is clear, New Mexico needs to initiate additional pension reform proposals. Reforms that would improve the system’s long-term funding, amortize the debt over shorter period, consider new pension plan designs that would reduce liability risks, expand portability, and improve retirement security— beyond its most recent effort— are needed if the state wants to make meaningful progress in securing pensions for its teachers and alleviate some of the tax burdens for future taxpayers.