In July 2022, the Federal Reserve System estimated there’s a 60% chance that the United States will enter a recession, under a tighter monetary environment, by the end of 2023. Since the U.S. reported two negative quarters of gross domestic product (GDP) in the first two quarters of 2022, technically the country is likely already in a recession.

Recessions can hit retirees and public pension plans hard, so public pension plans reporting large investment losses for 2022 could just be a prelude to rough times for public pension systems. A continued market downturn could potentially add trillions to public retirement systems’ existing pension debt, and most public pension plans are poorly positioned to withstand a major recession.

The largest pension system in the country, the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), reported a -6.1% return for 2022. The Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) recently posted a -14.5% loss for its 2022 fiscal year.

The good news: A single year of returns generally has a limited impact on a pension plan’s long-term horizon, whether that be the great double-digit investment returns that many pension systems reported in 2021 or the losses that many plans are reporting for 2022.

What matters most to the long-term funding of public pension systems is the ability to average out to, or come in above, the set investment return target so the plan has the money to pay for promised benefits.

The next investment return prospects over the next 10-to-15 years for institutional investors look slim. Stubbornly high inflation and other economic factors may be increasing the likelihood of a recession in the near term, but for several years forecasts have been warning pension systems to lower their long-term investment return expectations. In 2022, J.P.Morgan Asset Management, for example, has retained muted average return projections for U.S. public equities, the largest investment category for pension plans, at 4.1% for the next 10-15 years.

The Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS) is a good example of what could happen if a major recession scenario occurs over the next year and investment returns are low for a few years. TRS has already accrued $47.6 billion in pension debt since 2002. Most of TRS’ debt is due to investment returns falling below the plan’s lofty expectations, which were set at 8% until 2018.

Since then the retirement system was wisely started to lower its investment return assumptions. In July, the TRS Board of Trustees prudently decided to lower its assumed rate of return from 7.25% down to 7%. An actuarial projection reveals, however, that TRS is still quite vulnerable to a major market downturn.

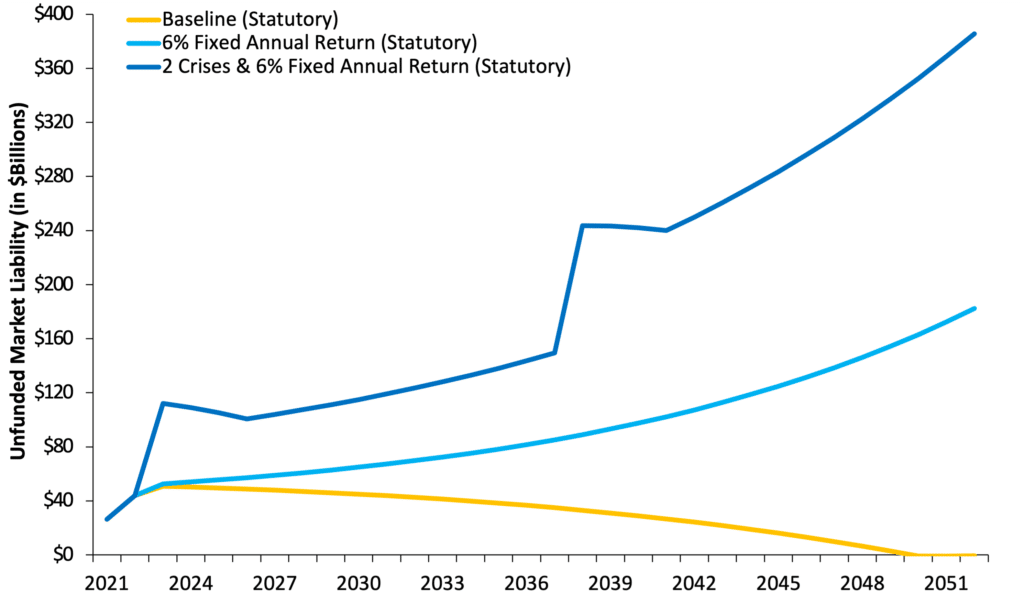

The analysis below (figure 1) applies -26% investment losses in the year 2023 and another in the year 2038, with each of those years followed by three years of a positive 11% rebound. Under that scenario, TRS’ unfunded liabilities, inflation-adjusted, are projected to grow from $44 billion in 2022 to $386 billion by 2052, leaving the plan roughly 52% funded.

Constant 7% returns, the system’s own baseline expectations, and 6% return scenarios are also shown for comparison. This forecast demonstrates that despite recent moves to better shield the system, TRS remains very vulnerable to major recessions. Even though the plan’s debt is currently expected to fall, the investment return assumption that was recently lowered to 7% could still set the plan up for future debt. TRS’ debt is expected to grow steadily if the plan realistically produces 6% returns each year.

Figure 1. Forecast of Texas TRS Unfunded Liabilities: Current Statutory Contribution Policy

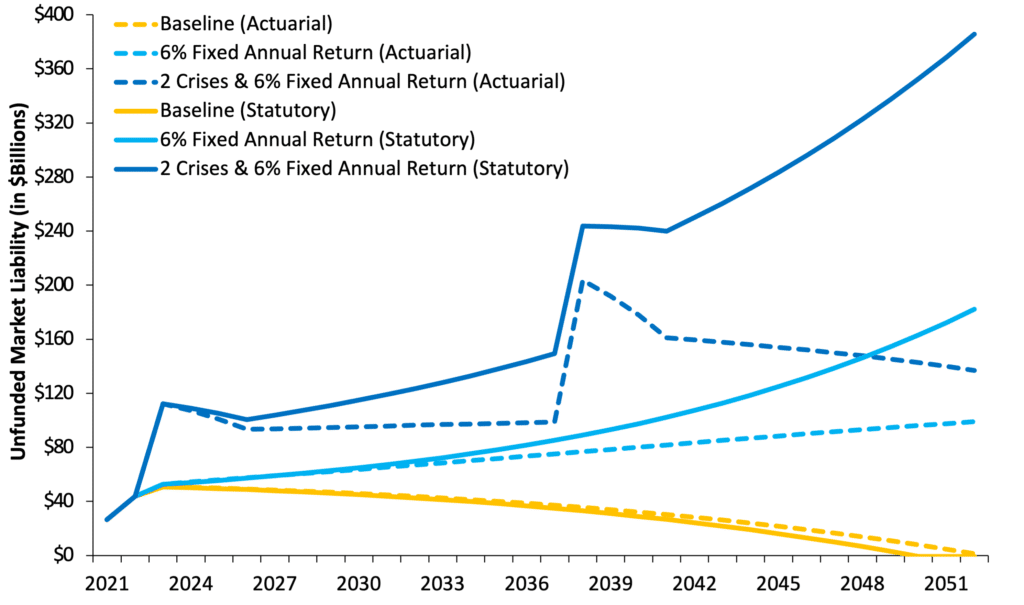

Further analysis (figure 2) suggests that Texas policymakers could greatly reduce the impact of a recession on the teachers’ plan by adhering to the contributions calculated by the plan’s actuaries— rather than continuing to base these payments on rates set in statute. If Texas were to transition to actuarially determined employer contributions (ADEC) for TRS, it could shave hundreds of billions off the state’s unfunded liabilities by 2052 (the debt would grow by just $92 billion instead of $340 billion) in the two recession scenarios described.

Figure 2. Forecast of Texas TRS Unfunded Liabilities: ADEC vs Statutory Contribution Policy

The Teachers Retirement System’s lowered investment return assumption does position the plan to be more resilient to lower future returns, but most 10-to-15-year projections suggest that TRS needs to continue to reduce its investment return expectation.

Forecasting shows that state policymakers should also consider paying actuarially required contributions (ADEC) to ensure adequate funding. Additional ways to bolster the funding of TRS would be to pay down pension debt faster and to consider alternative risk-reduced options for new hires:

These recommendations apply to most public retirement systems as well, as many pensions carry similar risks and would face equally difficult funding challenges were they to see a recession over the next year.

Seeing the heightened risk of a major recession in the near term, not to mention the many credible economic forecasts of muted investment returns over the next decade, policymakers need to actively seek out reforms that bolster the long-term funding projections of public pension plans. A failure to fully prepare for potential recessions opens public pension systems—and therefore taxpayers and future government budgets—to significant long-term funding and cost challenges.