When President Donald Trump nominated former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi to be attorney general of the United States, he emphasized Bondi’s track record cracking down on drugs and fentanyl and essentially promised to take that approach nationwide to save many lives.

And if you remember, in Florida, Bondi was trumpeted during her terms from 2011 to 2019 for cracking down on “pill mills,” putting in place restrictions on prescription pain killers, and suing the CVS chain for allegedly causing the opioid epidemic with loose prescription practices.

Unfortunately, according to Florida Department of Health data, drug overdose deaths in the state nearly doubled from 13.7 per 100,000 residents in 2011, when Bondi took over as the state’s attorney general, to 25.1 deaths per 100,000 residents in 2019 when she left office.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, overdose deaths increased dramatically nationwide and in Florida.

While overdose deaths have since gradually decreased, they are still well above pre-pandemic levels at 30.8 per 100,000 residents in 2023.

Several events are taking place here that provide important lessons and tell us what to expect in the next four years.

Bondi is a national champion of what is called the “overprescription” hypothesis, which blames rising rates of opioid overdoses starting in the early 2000s on increasing prescribing of opioids starting in the 1990s. There is some truth in that.

As opioid prescribing increased in the two decades before 2010, prescription opioids became the leading cause of drug overdoses.

The response that Bondi helped to champion, which was followed in most states and funded with federal grants, was prescription drug monitoring programs, which are state laws limiting the number of pills a patient can receive.

The Drug Enforcement Administration also ordered prescription opioid manufacturers to reduce opioid production.

These approaches made perfect sense to policymakers at the time. Bondi made her implementation of the E-FORCE PDMP a centerpiece of her accomplishments as state attorney general, and it probably makes sense to you reading this.

The problem is that everyone involved in drug policy, including Bondi, had a steady drumbeat of evidence that the prescription drug monitoring program approach caused a rapid increase in opioid overdose deaths. This was true in states nationwide, including Florida, where the rate of opioid overdose deaths remains far more than double where it was in 2010.

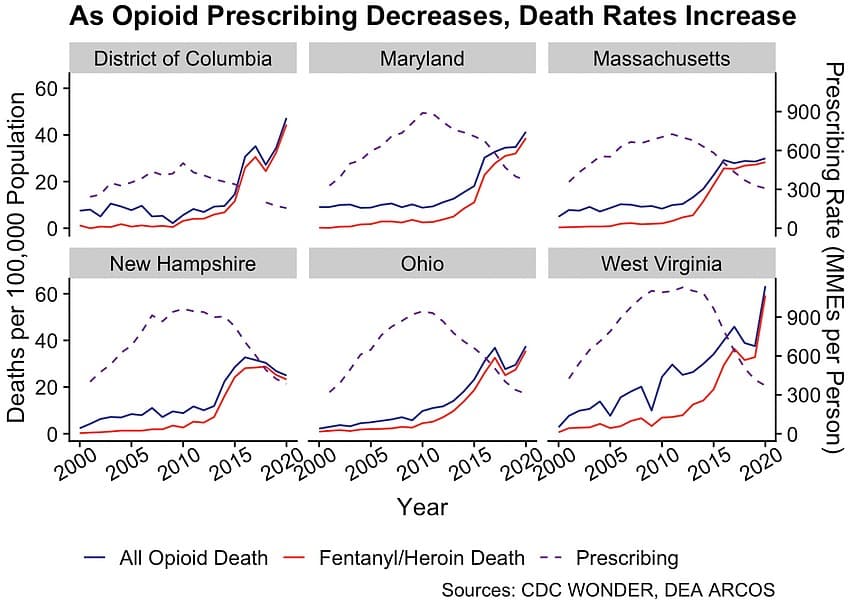

Look at the accompanying graph showing what happened in five states and Washington, D.C., when prescription monitoring was put into place between 2000 and 2020. As prescription rates declined, opioid overdose deaths rose.

At first thought, this seems counterintuitive. However, these results should have been easy to expect and easy to see in the annual data on opioid prescriptions and overdose deaths.

Our history of drug prohibition consistently shows that when the government restricts access to something people want, it drives demand to the illicit market. In this case, abuse of prescription opioids was a growing problem, but it was a fairly safe way to consume opioids. Once PDMP cut off that supply, just as alcohol prohibition in the 1920s pushed bootleggers to switch from beer to potent bathtub gin, opioid traffickers switched to fentanyl and its ilk.

Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health show that pain reliever abuse rates have flattened out since 2002, while heroin and fentanyl abuse rates increased only after opioid prescription rates started to decline.

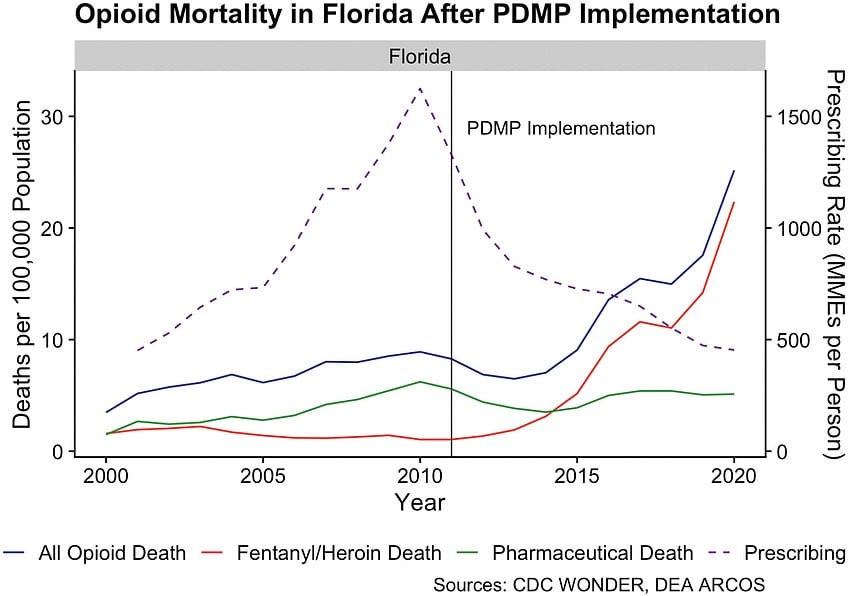

You can see this clearly in the accompanying graph on opioid mortality in Florida. When PDMPs were enacted in 2011 and prescription opioid prescribing declined, deaths from fentanyl and heroin began to skyrocket.

You would think policymakers in Florida and nationwide would look at these data and suspect that prescription drug monitoring programs and similar policies are not working. But you would be wrong.

Instead, they have clung to a simple narrative, often used by Bondi in her press releases, that PDMPs reduced deaths from prescription opioids, ignoring data showing vastly more deaths from other opioids.

It is particularly tragic that we are seeing rising overdose deaths at a time when the United States is enjoying an appreciable drop in drug addiction rates.

Opioid addiction, in particular, has been dropping for years. In 2002, 9.4% of Americans were addicted to a drug, including 0.7% of Americans addicted to opioids. In 2019, the last year measured with a comparable standard (DSM-IV), 7.4% of Americans were addicted to substances, with 0.6% of those being addicted to opioids.

Additionally, record levels of naloxone and addiction treatment medications are being distributed, which means more people received addiction treatment in 2021 than any other year in American history.

Fewer Americans are addicted to drugs, and more of those who are addicted are receiving medication-assisted treatment for addiction, yet more people are dying from drug use.

The reality is that drug addiction and drug-related deaths don’t have much of a relationship. Drug-related deaths are almost solely caused by the safety of the drug supply, which is made more dangerous by drug enforcement like PDMPs.

The shift from prescription opioids to fentanyl and heroin meant those with substance use disorder began dying at such a high rate that overdoses are spiking despite a shrinking population of regular drug users.

This raises the question of why we still have too many people with a substance use problem.

Researchers point to a plethora of causes, including poverty and financial distress, severe fears and anxieties, and difficulty getting mental health treatment and addiction treatment. The summary, as best we can tell, is that many people have something in their heads or their lives that they are so desperate to escape that they will use even a very dangerous drug like fentanyl to get that escape.

Making a drug illegal has done little to reduce the number of people wanting it. But the false narrative of the drug war is easy to explain and easy to pursue.

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to figure out why people are hurting so badly and, even more difficult, how to help them deal with it in a healthy fashion.

It’s no surprise that policymakers tend to choose the easy route, regardless of whether it works. Bondi was no different. Nevertheless, there are other ways that can work.

In France, policymakers addressed the state’s overdose epidemic by relaxing regulations on medication-assisted treatment, which combines addiction therapy with less dangerous prescription opioids. The result was a 79% drop in overdose deaths in four years.

We don’t expect Attorney General Bondi to have learned from what her drug policies wrought in Florida or to change her approach when applying it nationwide. So, unfortunately, we can likely look forward to at least another four years of troubling numbers of opioid deaths that could be prevented.

A version of this commentary originally appeared in the Sarasota Observer.