The extended period of low interest rates we’re in is not only creating challenges for public pension systems across the nation, but it is also negatively impacting people who are relying on their own savings to fund their retirements.

A common strategy for generating retirement income is to invest savings from an individual retirement account (IRA) or 401(k) into income-producing assets such as corporate bonds. But interest rates on corporate bonds have been falling in recent decades, reaching multi-decade lows in 2020.

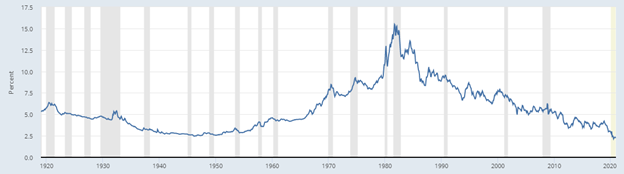

Figure 1 shows yields on highly-rated corporate bonds from Moody’s posted on the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s FRED website:

Figure 1: Moody’s Seasoned AAA Corporate Bond Yield

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Although this series dates back only to 1983, comparable Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) suggests that current rates are at levels not seen since the early 1950s.

The decline in interest rates since the 1980s has multiple causes. One is lower inflationary expectations: during and after the high inflation of the 1970s investors demanded high rates on fixed-income investments to compensate for the potential loss of purchasing power.

But interest rates have continued to fall during the persistently low inflation environment of the 2000s. Today, real interest rates (i.e., interest rates adjusted for inflation) on short-term Treasury bonds are negative. In November 2020, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland reported an expected inflation rate of 1.37 percent, well above the one-year Treasury bill yield of 0.11 percent.

Interest rates are even lower in some other advanced economies. At the end of November 2020, one-year German government bonds were yielding -0.69 percent.

Some believe that ultralow interest rates are, in part, the result of a global savings glut. As former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke argued in 2015: “a global excess of desired saving over desired investment, emanating in large part from China and other Asian emerging market economies and oil producers like Saudi Arabia, was a major reason for low global interest rates.”

But lower energy prices in the last few years have reduced the income of oil-producing nations, cutting into their flows of investable capital. China’s foreign exchange reserves are also well below their 2014 peak. Yet, interest rates remained relatively low, and as Figure 1 shows, have been falling since 2018.

Another possible explanation for the secular decline in interest rates is a series of Federal Reserve actions that began under the chairmanship of Alan Greenspan. The Greenspan Fed implemented expansionary monetary policies in response to financial disruptions such as the 1987 stock market crash, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the collapse of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998, and the 2001 recession. Financial commentators coined the term “Greenspan put” to characterize the Federal Reserve policy, which resembled the actions of stock market traders using options to insure their portfolios. Aggressive Fed intervention continued under Greenspan’s successors, most notably under Ben Bernanke during the Great Recession (2007-2009)m and Jerome Powell in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic.

To prop up the stock market, the Fed reduced the rates it charges to banks and purchased a variety of debt instruments with the effect of elevating their prices and lowering their yields. And the Fed often failed to fully withdraw prior stimulus before finding the need to intervene further. For example, in 2008, the Federal Reserve began rapidly expanding its balance sheet under a policy known as quantitative easing (QE). The central bank continued bond purchases under its QE policy until 2014 and only began to shrink its balance sheet in 2017.

As Figure 2 shows, the Fed made relatively minor reductions in assets before initiating a fresh round of QE in 2020.

Figure 2: Total Assets Held By the Federal Reserve System

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The degree to which Fed intervention has produced today’s record low-interest rates is open to debate.

Economist Jeffrey Rogers Hummel argues that the Fed’s balance sheet, while large, is a small fraction of the overall size of the debt capital markets in which it participates. The fact that most financial assets are outside the Fed’s direct control may limit its impact on rates. On the other hand, many fixed-income assets have little or no secondary market activity (i.e., they are held to maturity by their original purchaser), so Fed purchases influence interest rates more than its relative share of the fixed-income asset universe might indicate.

Carmen Reinhart, now chief economist at the World Bank, and her co-author Belen Sbrancia, an International Monetary Fund economist, argued in 2015 that the US Treasury, Federal Reserve, and many international financial overseers have implemented low interest rate policies in the past to reduce debt service costs relative to government revenue. They categorize this as a form of financial repression, not unlike more overt measures such as interest rate ceilings and foreign exchange controls. They see these forms of financial repression as an implicit tax on savers by depriving them of the greater income that would be available in an unfettered capital market.

Unfortunately, given the accumulation of federal debt in the United States since the early 2000s, financial repression through Federal Reserve bond purchases may need to be an ongoing phenomenon. Currently, interest on the federal debt totals around $376 billion per year. If the average interest rate on publicly held Treasury securities rose to 5 percent, a level was last seen in the 1990s, interest costs would rise to over $1 trillion a year, which is about one-third of 2020 federal revenue.

Low Treasury interest rates also pose a challenge to defined-benefit pension systems because these systems typically depend on asset growth to meet future pension payments. As risk-free interest rates fall, managers of defined-benefit systems must either lower their assumed rate of return (thus increasing actuarially determined contributions) or take on additional risk to try meeting return expectations. Because very few public pension systems are lowering their assumed rates of return we have seen a significant increase in public pension debt in the last 20 years. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the economy and state budgets, the total public pension debt nationwide equaled $1.2 trillion.

As Pension Integrity Project analyst Alix Oliver noted, without adjusting to this ‘new normal’ low-interest-rate environment “pension systems will be vulnerable to economic and market shocks in the future, which would likely continue to crowd out other priorities in government budgets and force unfair deals upon some stakeholders.”

Likewise, lower interest rates can dramatically affect the retirement incomes of individual savers. A worker retiring in the 1980s could have obtained a comfortable income by investing his or her savings in AAA-rated corporate bonds. Back then, a $1,000,000 investment would have generated $80,000 or more in annual income. Today, a similar investment would generate only $25,000.

An alternative to living off the interest generated from retirement savings is to annuitize those savings. By purchasing a fixed, single-life annuity from an insurance company, a saver can generate a guaranteed, higher level of income for the rest of his or her life. At death, annuity payments stop, and nothing is left to the annuitant’s heirs. Annuitizing one’s nest egg generates more income because the retiree is receiving payments that include both interest and principal. An annuity is roughly analogous to a defined benefit pension.

But higher life expectancies and lower interest rates have made annuities more expensive according to data provided by ImmediateAnnuities.com. In 1986, a 65-year-old male could purchase an annuity that would provide $5,000 per month of income for about $500,000. In early 2020, the same annuity would have cost about $1,000,000 (1986 and 2020 amounts in current dollars). To obtain an income flow with the same purchasing power as $5,000 per month in 1986, the 65-year-old male would have to invest about 2.5 times more.

Adding cost-of-living adjustments to an annuity makes it even more expensive. Cost-of-living adjustments make automatic increases to payouts based upon inflation. To purchase a $5,000 monthly annuity with a 3 percent cost-of-living allowance, the 65-year-old male would have had to pay about $1.4 million in early 2020—40 percent more than the fixed annuity.

In summary, financial repression, which Investopedia says “describes measures by which governments channel funds from the private sector to themselves as a form of debt reduction,” and public pension plans’ reluctance to adjust their assumed rates of return to accurately reflect today’s low-interest-rate environment are both contributing to growing pension debt.

This debt is burdening taxpayers with significantly increased costs and making future generations pay for the services of past public employees. Lower interest rates have also made it more expensive for retirees to create sufficient, secure income streams with their own savings.

Policymakers should give more consideration to the adverse impacts that repressive interest rate policies have on both public and personal retirement savings.