Just two years after sweeping reforms were made to set the Colorado Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERA) on a path to improved funding, the state’s Joint Budget Committee is considering options that would postpone some of those changes and even permanently reduce supplemental contributions that were implemented in 2004. The proposal is an attempt to reduce the short-term costs associated with PERA, in anticipation of what will obviously be a difficult year for Colorado’s revenue and pension assets.

While the coronavirus pandemic and economic downturn are making the need for budget-saving actions very real, Colorado policymakers should understand the long-term costs of shorting PERA contributions in 2020.

A major part of the 2018 pension reform—which had significant bipartisan support—was a direct annual distribution of $225 million into the pension fund from the state budget. The purpose of this additional infusion of cash was to make up for several decades of significant shortfalls in investment returns and pension contributions, among other factors that have been a drag on PERA’s funding. As a part of the current Joint Budget Committee (JBC) proposal, the state would suspend this funding assistance for two years, picking it back up in the summer of 2022 and continuing (as originally planned) into perpetuity.

The JBC is also considering putting a pause on newly established automatic adjustments, which were instrumental in setting up guard rails to ensure retirement security for Colorado’s public workers. A major piece of the 2018 reform effort included a feature that adjusted pension contributions in the case of payments being insufficient according to PERA’s actuaries. As part of their budget-balancing recommendations, the JBC is advising the state suspend what would have been an automatic increase of 0.5 percent in 2020 contributions.

Lastly, the committee is proposing a permanent reduction in Amortization Equalization Disbursement (AED) and Supplemental Amortization Equalization Disbursement (SAED) payments into the State Division. These additional payments have been a part of the state’s commitment to paying off growing funding shortfalls since 2004 and 2006 respectively, and are currently an essential part of PERA’s plan to reduce long-term costs and reach full funding within a 30-year window. The proposed action from the JBC would cut this payment to the State Division in half, dealing a major blow to the long-term solvency of the state’s pension system.

Analysis of the changes proposed above illustrates the long-term costs of taking a short holiday on SB 200 reforms and a permanent one on the aforementioned supplemental contributions. When evaluating the true long-term cost of any pension-related action, it is important to consider two factors:

- First, one must calculate the difference in contributions, both in the short-term and the long-term (for this analysis, a 30-year window is used to evaluate the long-term).

- Second, it is essential to forecast the unfunded liability that will exist at the end of the long-term period.

Adjusting contributions, as the JBC proposal suggests, usually changes a plan’s path toward full funding. Forecasting these proposed contribution pauses and reductions will clearly result in a plan that is less likely to reach full funding within the advised 30-year timeframe.

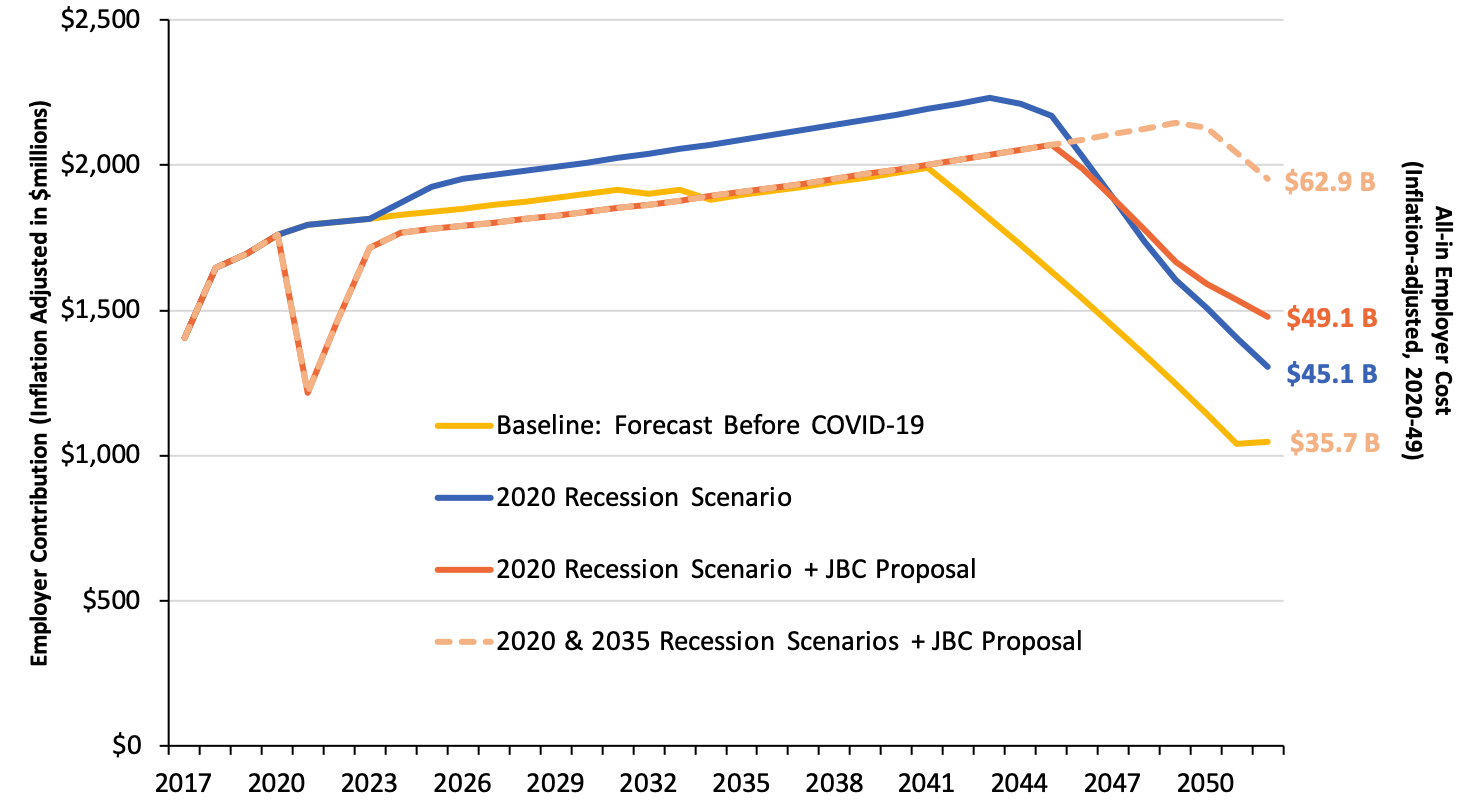

Adding both the combined 30-year employer contribution with the ending unfunded liability equals what we call the “All-in Employer Cost,” which allows us to compare the total cost to government employers of one path relative to another. Using this method, we have mapped the contributions and ending All-in Costs for PERA’s school and state divisions both before and after the effects of COVID-19 on the plan’s assets and liabilities (this analysis assumes a 2020 recession and recovery similar to that of 2008). Then, we map out the changes in the total costs of the plan under the proposed 2020 response. The results show that, while the proposal would alleviate immediate budget needs, the changes would generate significant additional long-term costs, a result that would be even more exacerbated by yet another recession or continued failure to meet lofty return assumptions.

Figure 1: Baseline Forecasts of PERA Contributions and All-in Costs (State and School Divisions)

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERA State and School Divisions. Values are rounded and adjusted for inflation. The “All-in Cost” includes all employer contributions over the 30-year timeframe, and the ending unfunded liability accrued by the end of that timeframe.

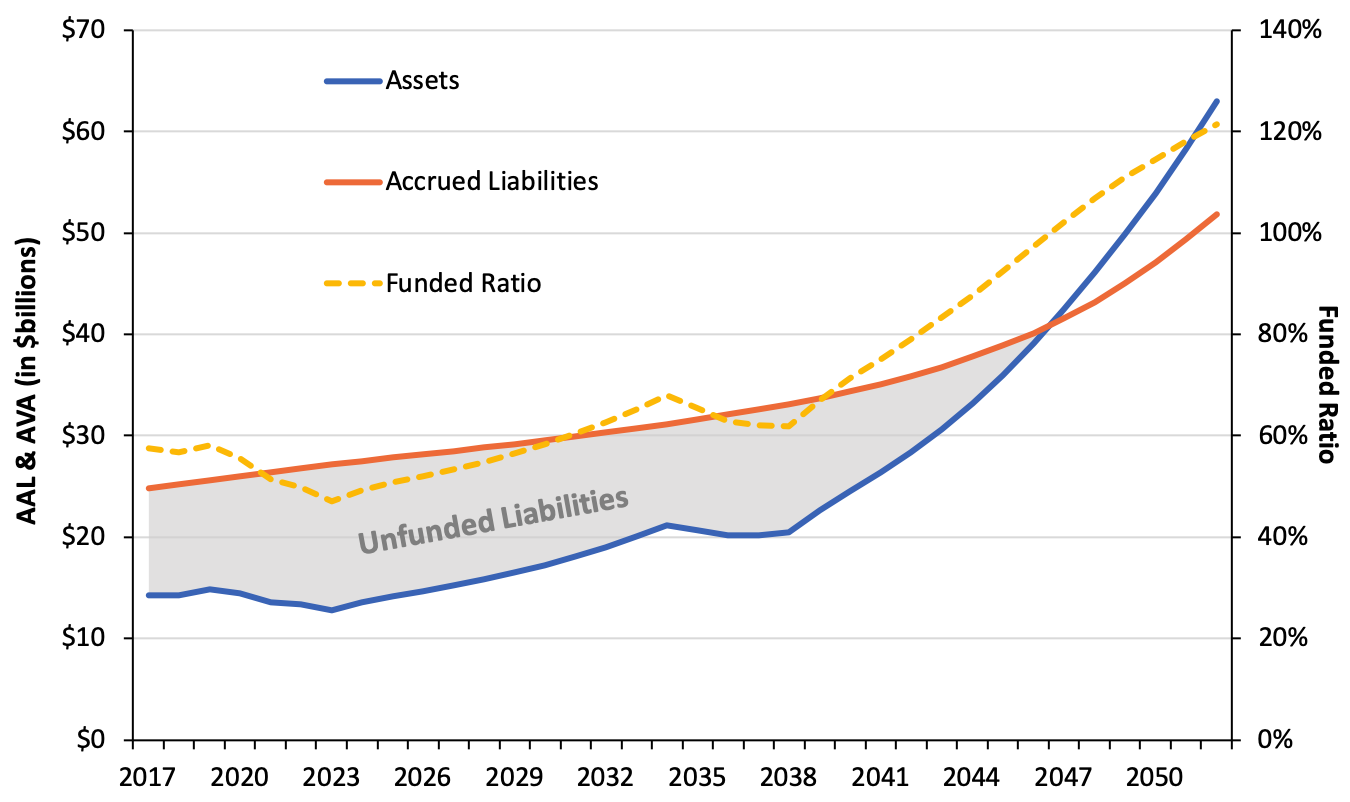

Most of the contribution reductions—and therefore most of the added long-term costs—come from permanently halving AED and SAED contributions in the State Division. This result is very visible in forecasts of State Division’s funding under a scenario of multiple recessions over the next 30 years. Figure 2 shows that, assuming actual long-term returns that match PERA’s pre-COVID expectations, after the 2018 reforms the fund was structured to withstand two individual recessions over the forecasted timeframe. Despite two 2008-like hits to the fund’s assets, the State Division would still be able to rebound and reach full funding by 2047.

Figure 2: Baseline Forecast of PERA Funding After 2020 & 2035 Recessions (State Division)

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERA State Division. Scenario assumes 2020 & 2035 recessions and recoveries similar to 2008 and the plan’s assumed returns in other years.

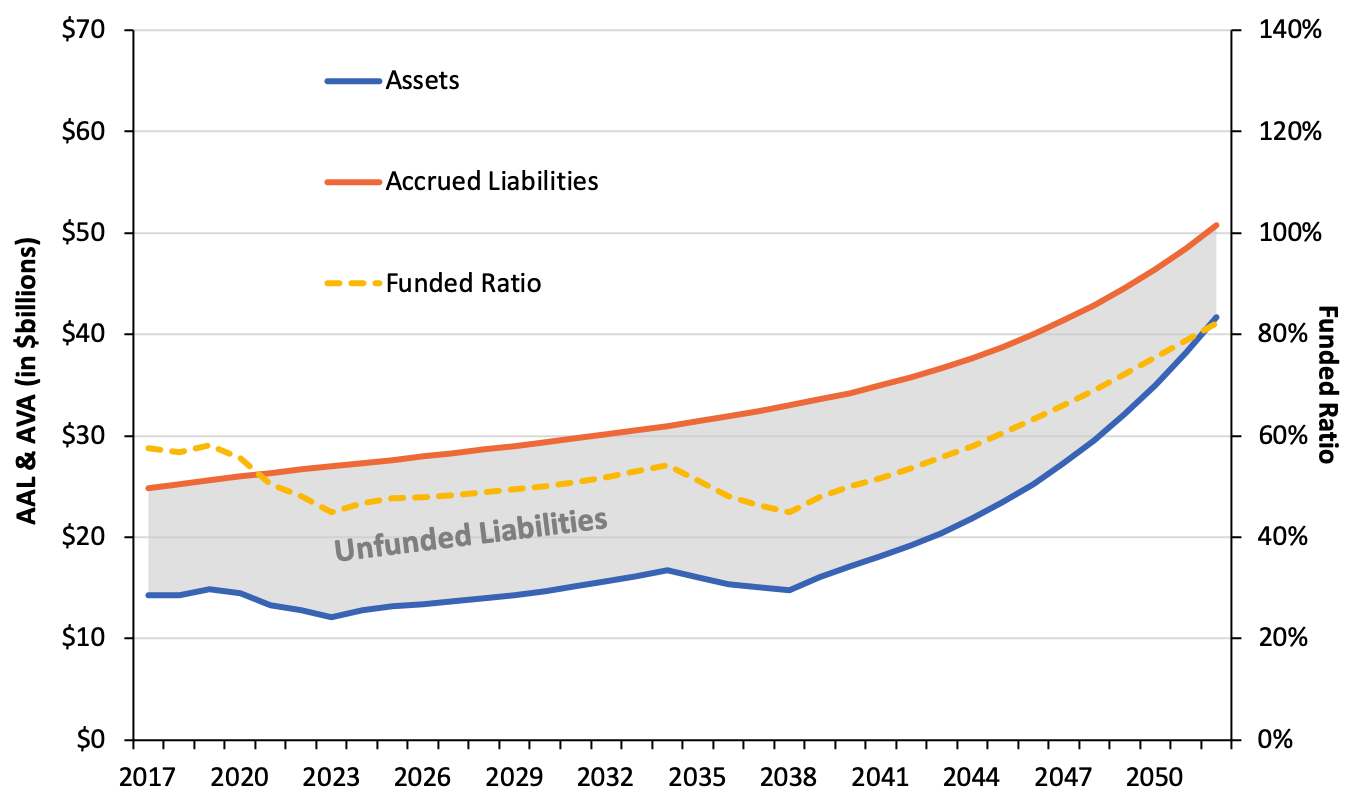

But a permanent reduction in AED and SAED payments would put the State Division on a much different path, as displayed in Figure 3. The proposed recommendations would significantly alter the long-term forecast of the fund so it would no longer reach full funding within the prescribed 30-year window under a scenario of two recessions and it would still be saddled with significant amounts of unfunded liabilities after that period. These results suggest that a permanent contribution reduction would negatively affect PERA’s resiliency to turbulent and unpredictable market conditions.

Figure 3: Forecast of PERA Funding After 2020 & 2035 Recessions and JBC Recommendations (State Division)

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERA State Division. The scenario assumes 2020 & 2035 recessions and recoveries similar to 2008, the plan’s assumed returns in other years, and contribution reduction recommendations according to the Colorado Joint Budget Committee.

Colorado policymakers are right to anticipate and plan for significant budget difficulties in the upcoming year. A recession will have wide-reaching impacts on how the state government operates in both the short- and long-terms. Significant market losses will surely affect PERA, and consequently the costs and security of retirement plans for public workers. While weighing policy options to alleviate these upcoming budgetary pressures, it is critical to understand not only the short-term savings but also the long-term costs that are attached to various proposals. If pension contribution policies are adjusted it would result in the addition of significant long-term costs and a public pension plan that is no longer en route to full funding within the prescribed 30-year window.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.