For the largest U.S. cities, the growing costs associated with paying past pension debts has resulted in tens of millions of tax dollars being diverted away from public services each year. The budget squeezing in municipalities will likely continue unless reasonable pension reforms are implemented.

As rightly pointed out by David Crane, Stanford University lecturer and member of the Society of Actuaries Blue Ribbon Panel on Public Pension Funding: “It’s one thing to pay higher tax rates for better services, quite another to pay higher tax rates to fund higher retirement costs.”

Indeed, S&P Global Ratings recently released a report that examined public costs in the 15 largest U.S. cities. The report found that 11 of these 15 cities had pension obligations that exceeded other fixed debt obligations (think of municipal bonds and other debt securities). Per Pension & Investments, last year these 15 cities, on average, slated as much as 13.5 percent of their annual expenditures for public pensions. This is not even accounting for Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB), another term for the retiree health care benefits that also tend to be chronically underfunded in many jurisdictions.

These pension contributions—which in many places have been driven higher by the additional amortization payments needed to help pay down unfunded liabilities—represent large portions of budgets that cities could have otherwise used to finance other crucial public needs, like road infrastructure, hiring more public safety officers, or tackling drainage and stormwater issues. Instead, these funds are increasingly being used to pay off legacy pension debt and the related interest that accrues on this debt.

Chicago, which we have covered previously, is perhaps the starkest example featured in the S&P analysis. According to Pensions & Investments, the Windy City dedicated as much as 27.6 percent of its 2017 budget to public pension contributions, more than twice the national average. Not stopping there, city officials recently considered—and put on hold —an audacious $10 billion borrowing in the form of pension obligation bonds to put a quick, but risky, Band-Aid on their pension underfunding.

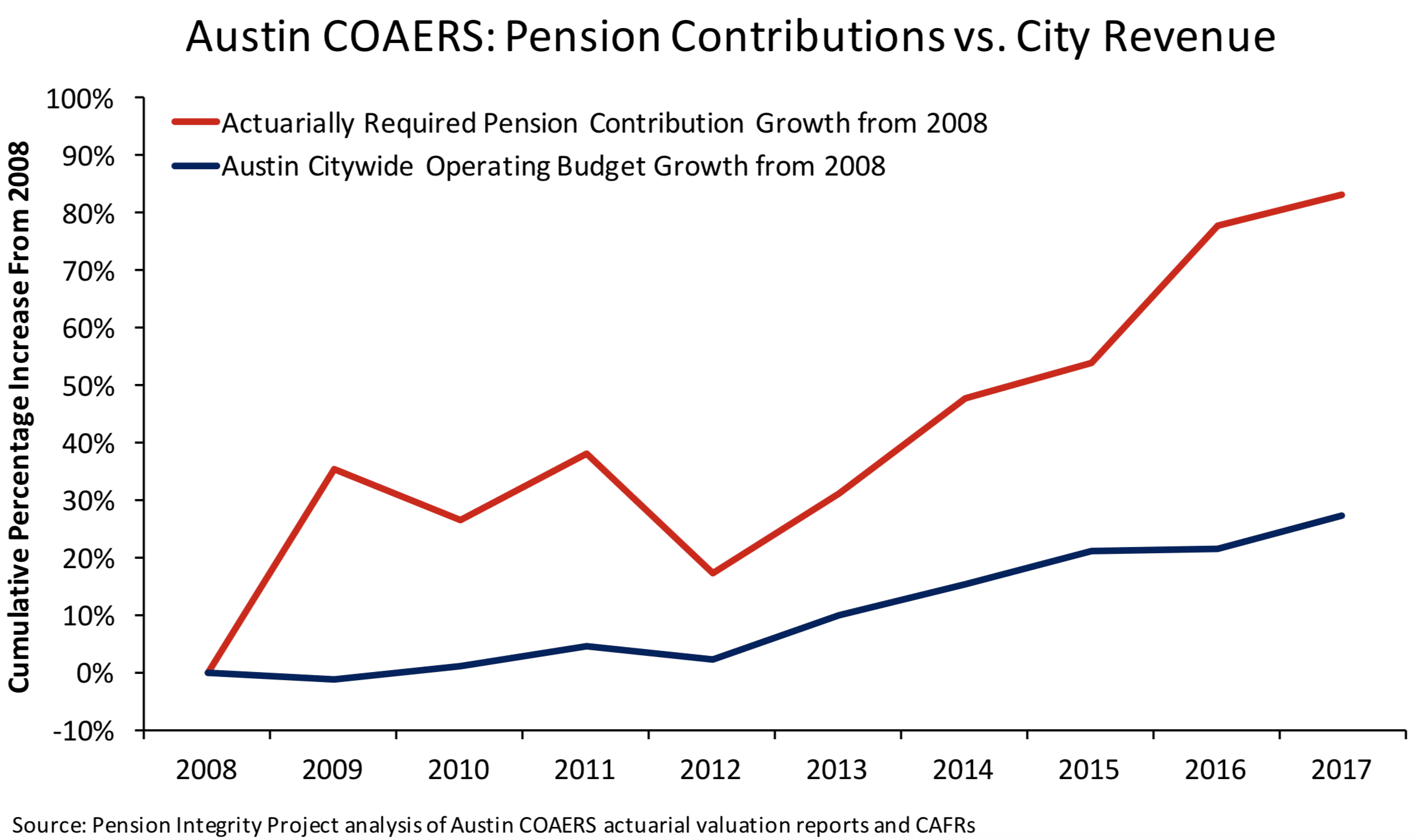

Another less striking example is the city of Austin, with 12.7 percent of expenditures going to pension costs. Per an update on initial Reason analysis, Austin’s actuarially determined employer contribution (ADEC) towards its Employees’ Retirement System (COAERS) increased 83.3 percent (inflation-adjusted) from 2008 to 2017. The city’s operating budget, however, increased just by 27.3% during the same period (see figure below). [Note: for additional analysis of the COAERS plan, see this May 2018 report jointly produced by the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation.]

Rubbing salt into the wound, U.S. cities are reporting a slowing of revenue growth this year, according to an annual survey by the National League of Cities. Obviously, rising pension contributions and lower revenue growth are a vicious combination for any jurisdiction to contend with from a fiscal perspective.

That is not to say that cities should not be making these additional pension contributions. On the contrary, failing to make ADEC contributions in full is one of the key reasons for systemic underfunding. Rather, what’s important is to find long-term reform solutions that ensure that promises are met while helping to avoid cutting back on other public service priorities down the road.

Make no mistake, the effects of pension underfunding spread much further than just crowding out immediate public service needs. The perpetual pension underfunding in Chicago, for example, has contributed to the city having one of the worst credit ratings in the country, which only recently saw slight improvements. This makes subsequent borrowings for any publicly-funded project a much more expensive endeavor. And the fact that Chicago is the only large city that experienced a reduction in population for the third year in a row, does not help its efforts in generating the revenue needed in the long-run to meet its growing pension liabilities.

For similar reasons, Moody’s downgraded Dallas’ general obligation bonds, citing pension-related factors. The Dallas Police and Fire Retirement System crisis was only recently addressed with a pension reform implemented last year.

Each of the 15 cities surveyed by the S&P Global Ratings has its own unique set of problems that contribute to the growth of public pension debt. Finding long-term reform solutions sooner than later is the only viable way to secure promised pensions, as well as the funds needed for other public service priorities in the future.

[1] Cities reviewed included Chicago, Dallas, Jacksonville, San Jose, Houston, Austin, Phoenix, New York, Columbus, San Francisco, San Antonio, Los Angeles, Indianapolis, San Diego, and Philadelphia.