Puerto Rico stopped paying interest and principal on its debt two years ago, and near-term prospects for bondholders remain bleak. While a federally-appointed financial control board spars with the commonwealth’s governor over a fiscal plan, creditors are engaged in drawn-out bankruptcy proceedings in which different classes of bondholders are fighting each other as well as the government. Meanwhile, the island is struggling to recover from Hurricane Maria, which took more than 1,000 lives, devastated local infrastructure and left millions without power for months. Now that the immediate crises have lessened, it is time for the federal and commonwealth governments to consider deep structural reforms—including innovative policies like territory-specific work visas and special economic zones—to rejuvenate Puerto Rico’s economy, fix its broken public finances and provide bondholders a decent recovery.

Given all the suffering that has accompanied Puerto Rico’s prolonged recession and disaster recovery, it might seem odd to worry about bondholders. Much of the island’s debt is held by so-called “vulture funds” who bought bonds at deep discounts in hopes of realizing outsized returns. These players are hardly sympathetic. But they only represent a portion of the creditor class: many middle-class individual investors both in Puerto Rico and the mainland are also losing out. Further, Puerto Rico’s ongoing insolvency prevents the government from financing new infrastructure while casting a shadow over the entire municipal bond market. If bondholders cannot expect reasonable and timely recoveries on defaulted bonds, they will hesitate to lend to Puerto Rico and potentially all other US municipal borrowers.

It wasn’t supposed to work this way, and the hurricane is only partly to blame. In 2016, Congress passed a Puerto Rico fiscal reform bill with bipartisan support. The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) gave Puerto Rico access to federal bankruptcy court while imposing a federally-appointed financial oversight board. Under the bill, Puerto Rico was given time to work out its debts, while being obliged to cut wasteful spending and improve fiscal transparency.

Unfortunately, the government, the oversight board and creditor groups failed to agree on a debt restructuring plan during the time allotted by PROMESA – the law’s stay on bond litigation ran out long before Hurricanes Irma and Maria landed. The dispute is now in federal bankruptcy court where the proceedings are chewing up tens of millions of dollars in legal fees — dollars that could instead be going to bondholders, and the commonwealth’s employees and/or retirees.

Meanwhile, the Puerto Rico government is over three years behind in producing audited financial reports and is refusing to implement spending reductions mandated by the oversight board. Representative Rob Bishop (R-UT)—who played a major role in crafting PROMESA—recently criticized the oversight board for allowing the commonwealth government to circumvent its authority and for its inadequate outreach to bondholders.

With roughly $70 billion in bond obligations and another $50 billion in unfunded pension liabilities, Puerto Rico has an unmanageable debt burden, and the problem becomes worse as the island’s economy continues to shrink. Restoring economic growth is crucial to ensuring that creditors see a meaningful recovery: not 100 cents on the dollar but something more than a token percentage.

The Economic Challenge Of Chronic Population Decline

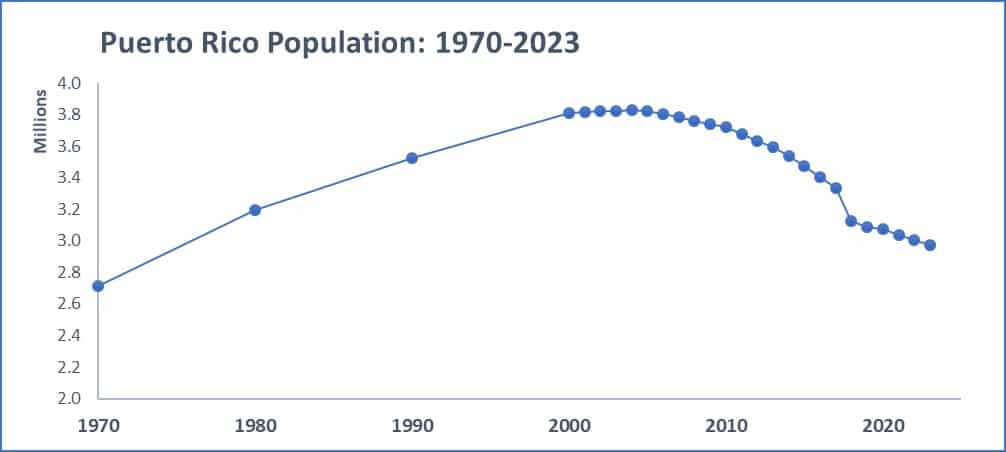

To achieve economic growth, Puerto Rico will have to halt and then reverse its chronic population decline. As the accompanying chart shows, the island’s population peaked in 2004 and has recently fallen back to levels not seen since the 1980s. During the last calendar year, 275,000 more passengers departed Puerto Rico airports than arrived, mostly in the wake of the destruction wrought by Hurricane Maria. The majority of those leaving are unlikely to return soon if ever: Florida and other states offer better opportunities than—and more than double the wages of—the stagnant Puerto Rico economy.

Government projections show a further population decline through 2023 when the number of residents is expected to fall below three million — a level last seen in the 1970s. Aside from out-migration, the commonwealth is also afflicted by a low birth rate. According to World Bank statistics, Puerto Rico’s crude birth rate (the number of births per thousand population) fell from 15.6 in 2000 to just 9.0 in 2015, well below the 2015 US rate of 12.4.

Reversing Population Decline through Territorial Work Visas

With insufficient births and the exodus to the mainland, Puerto Rico can only stabilize and grow its population by attracting newcomers. The commonwealth has enacted multiple laws designed to attract wealthy Americans by providing them with tax incentives. For example, Act 22 offers new residents a 100 percent income tax exemption on capital gains, dividends and interest. But these laws are only attracting a tickle of mainlanders. In 2015, the Census Bureau estimates that only about 9,000 US residents not of Puerto Rican origin moved to Puerto Rico, little changed from the levels seen before the tax incentives took effect.

If Puerto Rico cannot attract other Americans, it should be able to attract foreigners, especially individuals from Latin America who share the island’s Spanish language. Right now, prospective Latin American immigrants are attracted to California, Florida, Texas and other mainland states because of their stronger economies.

But if the federal government allowed Puerto Rico to issue territorial visas, it could attract individuals from Venezuela and Central America now living under difficult conditions who would not otherwise be granted admittance to the US. By issuing territorial visas, Puerto Rico would not be able to grant US citizenship or even a path to US citizenship, but it could give a new class of immigrants work permits and/or permanent residency in the commonwealth.

The idea is somewhat akin to one advanced by my Reason colleague Shikha Dalmia. She has advocated state-based work permits, an idea that took legislative form last year. S.1040, the State Sponsored Visa Pilot Program Act of 2017 introduced by Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), would allow states to provide visas that would allow aliens to “perform services, provide capital investment, direct an enterprise, or otherwise contribute to the state’s economic development.”

S.1040 does not include Puerto Rico, sets a low limit of just 5,000 visas per state per year and does not allow states to offer permanent residence. Because Puerto Rico is separated from the rest of the US by an ocean, is primarily Spanish speaking and is experiencing an economic crisis, it needs to and should be able to take advantage of much more liberal limits without raising the same red flags that normally worry immigration opponents.

When I previously suggested this idea, commenters had a fair question: since Puerto Rico has a high unemployment rate, how would migrants find jobs? For this plan to work many of the new arrivals would have to start their own businesses, employing themselves and others in their cohort. Entrepreneurship is common among immigrants, including those who come to the US from Latin America.

Unfortunately, Puerto Rico is not a business-friendly place. The World Bank ranks Puerto Rico 64th in the world in its Ease of Doing Business Survey, well below the US, which ranked 6th. Puerto Rico scores poorly in such areas as dealing with construction permits, registering property, paying taxes and enforcing contracts.

Sparking Economic Growth through Deregulation, Special Economic Zones

To absorb new arrivals and allow them to become economically productive taxpayers, Puerto Rico needs to reduce red tape, a task that may be easier said than done given political support for the various regulations Puerto Rico has implemented.

An alternative to island-wide deregulation would be the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) that provide a much greater degree of business flexibility. Puerto Rico already has a 4,500-acre free trade zone in which manufacturers are exempt from duties on imports of raw materials. Expanding this zone and offering more tax and regulatory variances could be a way forward.

SEZs have been successful elsewhere around the world, especially in China. Shenzhen, previous a small market town near Hong Kong, grew at an annual rate of 40% in the dozen years after Deng Xioaping designated it as an SEZ in 1980.

Two city-states that operate much like SEZs are Hong Kong and Singapore. Both of these small nations have joined the ranks of First World economies over the last half-century by offering relatively high levels of economic freedom and relatively low levels of taxation. More recently, the former Soviet republic of Estonia has followed the example of these Asian tigers, adopting free trade and a flat income tax (now 20 percent). Since 1995, its per capita gross domestic product (GDP) on a purchasing power parity basis has grown from 35 percent to 75 percent of European Union levels.

The potential for SEZs in Puerto Rico will be a topic of the Startup Societies Foundation conference at George Mason University on May 9-10. I look forward to discussing the benefits of both SEZs and territorial visas for Puerto Rico. Unorthodox ideas like these are needed to rejuvenate the island’s economy and provide value for its beleaguered creditors.