From 2001 to 2023, the most recent period with complete data available, 99% of public pension funds failed to meet their average assumed rates of return. The average investment return for public pension systems during this period was 6.5%, well below the average assumed rate of 7.59%.

The failure of public pension funds to reach their assumed rates of return has implications beyond the disappointing investment returns themselves. It means government entities have systematically underestimated the costs of providing public pension benefits to workers, unintentionally underfunding their pensions and creating public pension debt. As of 2023, public pension debt in the United States totals $1.6 trillion, which represents about a third of all state and local government debt.

Because most public pension plans guarantee benefits, regardless of investment performance, it falls on state and local governments to close any gaps between assumed rates of return and actual investment returns. Increasingly, governments are forced to choose between cutting public services and raising taxes to pay for pensions.

The underperformance of investment expectations

Excess returns measure how investments perform relative to expectations. For this analysis, they are defined as the pension’s actual returns minus assumed returns. Positive values indicate that public pensions have achieved returns above expectations, while negative values indicate the opposite.

The assumed rate of return (ARR) is, as the name suggests, the rate of return pension systems assume their investments will generate. It is an investment benchmark determined by a weighted medium-term average expected return for each asset class within a pension portfolio. The assumed return is an essential input for pension contributions and funded estimates.

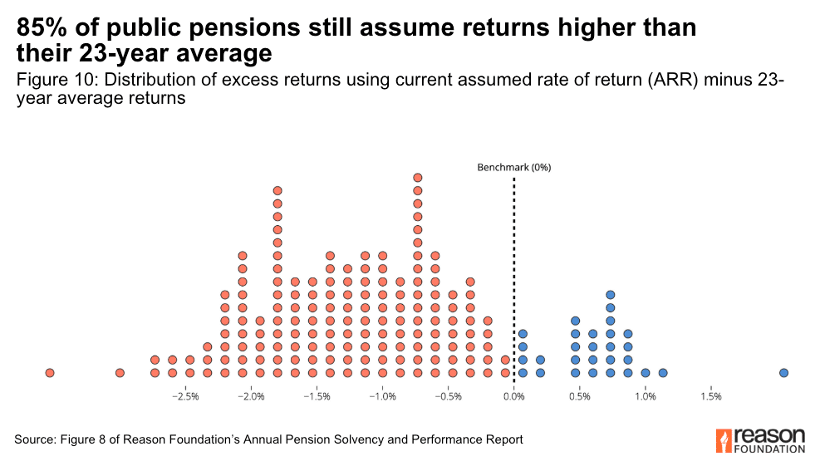

As displayed in Figure 1, subtracting the 23-year average expected investment returns from the 23-year average achieved returns shows that less than 1% of public pension plans achieved positive excess returns over the past 23 years.

There are significant disparities in the long-term performance of public pension funds. Some plans, such as the Kansas Public Employees Retirement System and the Pennsylvania Municipal Retirement System, have exceeded investment return expectations by having an average return 0.8% (8 basis points) higher than their average assumed rate of return over these 23 years.

However, most public pension systems have experienced unsatisfactory investment return results. For example, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, the largest public pension system in the nation, and Chicago’s largest pension fund have a historical performance that falls short of their targets by 1.98% and 2.05% (~200 basis points) annually on average, respectively.

At the bottom of the distribution, meaning they did the worst relative to their assumed rates of return, are Arizona’s Public Safety Personnel Retirement System and Arizona Corrections Officers Retirement Plan, whose returns missed their average assumed rates of return by 3.7% (370 basis points) over the past 23 years.

The consequences of overestimating investment returns

Investment returns are a crucial source of revenue for pension systems. According to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), between 1993 and 2022, investment earnings represented 63% of public pension revenue, more than employee and employer contributions combined.

Public pension investment assumptions directly affect the valuation of liabilities. Unlike the private sector, public pension liabilities are valued based on the expected yield of their returns, a practice called expected-return discounting. This creates a strong incentive for pension systems to overestimate investment returns or increase risk-taking, as a higher assumed rate of return decreases the value of liabilities, seemingly improving the funding optics of a pension plan.

Since pension contributions are estimated based on expected returns, when investments underperform expectations, public pension plans end up with less money than they anticipated—creating unfunded liabilities. Under most defined benefit plans, it’s the sponsoring government—and ultimately taxpayers—who must make up the difference to ensure retirees receive the promised pension benefits.

These shortfalls grow over time. Just like other forms of debt, unfunded pension liabilities accrue interest as the plan misses out on investment gains it would have earned if fully funded. The longer the shortfall persists, the more expensive it becomes.

Addressing the gap early limits this compounding interest. Delaying action allows the liability to snowball, making future solutions more costly.

Since the responsibility of fulfilling public pension promises, regardless of investment returns, ends up on taxpayers, realizing that pension funds cost more than assumed often creates the need to abruptly raise taxes or cut spending to deal with higher-than-expected contributions following a readjustment in investment return expectations. Thus, the overestimation of assumed rates of returns not only leads to inappropriately lower present contributions and increased future costs but also creates a potential shock to public financial planning that can surface at any time.

Another consequence of overestimating investment returns is that, by seemingly hiding the unfunded liabilities or improving funding optics of a pension system, it distorts the credit risk assessments of state and local governments. Understated public pension liabilities and contribution requirements mislead bondholders, counterparties, and lenders about an entity’s actual financial condition, leaving them exposed to more risk than they realize.

Sometimes, policymakers are worried about lowering a plan’s assumed rate of return to more realistic assumed rates of return because the public pension plan’s funded status deteriorates and the full extent of unfunded liabilities becomes more apparent. For pension managers and elected officials, this reckoning can be politically unpalatable, creating perverse incentives to delay it as much as possible, which increases pension costs for future generations of taxpayers and public employees.

Generalized reckoning and lower return expectations

Despite the challenges involved with lowering a public pension plan’s assumption on investment returns, nearly all pension systems have had to adopt lower return expectations to match their historical investment outcomes.

Over the past two decades, public pension funds have gradually lowered their assumed rates of return from an average of 8% in 2001 to 6.9% in 2023, more closely approaching the 23-year national average rate of return of 6.5%.

This generalized readjustment in assumed returns has led to a national increase in unfunded liabilities, as public pension funds have been recognizing that their investments have, and will, yield lower returns than they have been assuming, which means the taxpayers’ cost of providing pension benefits to public workers has been realized to be higher than previously projected.

In 2023, almost all public pension plans have assumed rates of return ranging from 6.8% to 7.2%.

As of the end of the 2023 fiscal year, the highest assumed rate of return among the 296 plans in Reason Foundation’s Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report is 7.5%. Public pension plans in Ohio, Iowa, Oklahoma, Texas, and Alabama top the list of highest assumed rates of return, despite most having underperformed these assumptions over the past two decades

On the other end, the lowest assumed rate of return in Reason Foundation’s Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report is 5.3%, which is that of Kentucky Employee Retirement Systems. Other public pension plans in New York, Michigan, Louisiana, DC, and Indiana are also among those with the most conservative investment return assumptions.

Despite widespread reductions in assumed returns over the last decade, the most recent edition of the Reason Foundation’s pension report estimates that 86% of public pension plans still assume returns higher than their 23-year average—which suggests that further downward revisions to ARRs are likely on the horizon, along with more increases in unfunded pension liabilities and catch-up hikes in government pension contributions.

Investment return assumptions play a critical role in a public pension system’s funding policy. When return expectations are set too high, they systematically understate the actual cost of public employees’ pension benefits—delaying contributions, distorting financial reporting, and discreetly passing liabilities onto future taxpayers.

Policymakers should ensure that investment return assumptions are grounded in realistic expectations, be mindful of historical investment performance, and proactively adopt funding practices that address shortfalls early to limit runaway public pension costs and debt.

For interactive reports and more analysis visit Reason Foundation’s Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report.