Arizona’s recent project to improve the solvency of its public safety pension plan is a notable fiscal achievement. With the passage of Senate Bill 1428, the state legislature has moved to slash the volatility of new hire contribution rates for local government employers by 50%, while simultaneously reducing the total forecasted accrued liabilities of the pension plan as a whole by more than a third over the next three decades.

The same pension reform effort installs a less expensive, more sustainable new tier of benefits and fixes a structurally unsound system for post-retirement benefit adjustments that was threatening the solvency of the plan.

And perhaps most notably, the pension reform package earned the endorsement of many public safety labor unions statewide because it is also providing secure retirement benefits for current and future employees.

The ideal public sector pension reform always includes reducing taxpayer exposure to risk, ensuring the cost for government employers is affordable and stable, and providing sustainable and secure retirement for current and future employees. But rarely does a pension reform effort accomplish all of these in one multifaceted package, as Arizona has done with the reform to its Public Safety Personnel Retirement System (PSPRS).

The details behind the Arizona SB1428 pension reform effort are worth considering in detail, particularly changes to the affordability of benefits, the volatility in employer costs for benefits, and the post-retirement adjustment of benefits.

Affordability of Pension Benefits

Arizona’s reform creates a new, more affordable tier of benefits for police, fire and other hazardous duty personnel hired on or after July 1, 2017. New public safety hires into PSPRS will be offered a choice between a Defined Contribution Only Plan and a Defined Benefit Hybrid Plan.

The Defined Contribution Only Plan offers employees a tax-deferred, professionally managed, portable 401(a) account with a menu of investment options to select from, based on risk tolerance and retirement goals. Under this option employers and employees each contribute 9% of compensation (i.e., monthly pay checks), creating one of the most attractive public safety retirement options in the country.

The Defined Benefit Hybrid Plan offers employees a traditional pension benefit based upon years of credited service at retirement or termination, the member’s final average compensation, and a defined benefit multiplier. This is similar to the existing defined benefit plan, but with several key differences that improve affordability:

(1) New Multiplier Formula: New employees who work for at least 15 years will receive a benefit multiplier of 1.5%, with the multiplier stepping up every two to three years. New employees who work a full career of 25 years will receive a 2.5% multiplier, which is equivalent to the benefit provided to current employees and retirees. (See our full analysis of the PSPRS reform for the complete schedule.)

(2) Pensionable Pay Cap: Compensation that can be considered for determining a pension benefit will be capped at $110,000 for new hires, as compared to the cap for current hires of $265,000. The cap can increase every three years at the same rate as the change in the upper limit of pay scales (salary ranges) for public safety positions during the same period—estimated to be 1% average annual growth.

(3) 50/50 Cost Sharing: All normal costs, administrative costs, and any potential unfunded liability amortization payments for new hire benefits will be split evenly. Currently, employees have a fixed contribution rate and taxpayers bear all the risk of unfunded liabilities.

(4) Retirement Eligibility: New employees will be able to retire at any age, with their benefit based on years of service to that point, but they won’t be eligible to start receiving their benefits until age 55, compared to 52.5 years old currently. Employees can elect to have their benefits start at age 52.5, but the benefit will be an actuarially equivalent amount, as if payments started at age 55 (i.e. the monthly amount will be reduced). Collectively, this means that assets will remain in the plan longer to earn investment returns.

(5) COLA Charge Included in Normal Cost and Linked to Funded Status: Retirement benefits are eligible for a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) up to 2% based on local rates of inflation, and the costs of providing this benefit will be included in normal cost, effectively pre-funding the benefit. This contrasts with the Permanent Benefit Increase (PBI) scheme in which benefit increases were not prefunded (see below for our full critique); it is better for plan solvency to prefund benefit payments than to just hope the assets of the plan have enough to cover a promised benefit increase. Further, if the funded status of benefits for new hires begins to erode, then COLA payments will be reduced or suspended until the plan regains funded status (below 90% funded the max COLA is 1.5%; below 80% funded the max COLA is 1%; below 70% funded there will be no COLAs paid).

Additionally, the Defined Benefit Hybrid Plan will offer a defined contribution (DC) 401a account to all new employees whose employer does not participate in Social Security—estimated to be about 65% of current hires. Employers will contribute 3% of compensation into these DC accounts, matched by 3% from employees (for a total 6% DC benefit). Thus, the total normal cost for employers and employees will vary depending on whether they participate in Social Security. This defined contribution benefit is intended to provide a degree of equity between employees who are and are not earning Social Security benefits.

So how much do these changes for new hires cut costs? All of the changes to the defined benefit plan reduce total defined benefit normal costs by about 25%—from around 21% of payroll to roughly 15% of payroll. This is accomplished by a combination of the changes to the multiplier schedule, retirement eligibility, and the pensionable pay cap. At the same time certain employees will also have defined contribution plans too, so for them the total normal cost for their benefits remains essentially cost neutral at around 21% of payroll once the 6% total defined contribution component to the hybrid plan is added.

However, the new 50/50 cost-sharing policy is a game changer for employer contributions. No matter what kind of hire a new employee is, employers will be saving money because the costs of that employee’s benefits are shared equally. Meanwhile, employees will not only have lower contribution rates under the new plan, no matter which option they choose, but will also have more control over the funding of their benefits with additional seats on the PSPRS board.

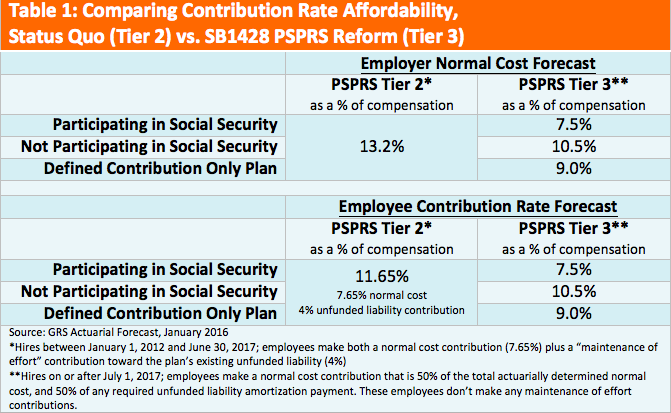

Table 1 shows a comparison of the forecasted costs for current employers and employees (new hires into PSPRS Tier 2) and for future hires under the reform (PSPRS Tier 3). Note that without the SB1428 reform, employers would be paying 21% to 43% more in normal cost—the difference in cost for continuing to hire employees into the current Tier 2 versus the new Tier 3. Employees meanwhile will have contribution rates that are 10% to 36% less, depending on whether they are in or out of Social Security, or choose the Defined Contribution Only Plan.

Finally, changes were made to PSPRS funding policy that will improve the plan long-term and reduce total costs to taxpayers. Long amortization schedules in general lower near-term costs, but increase the total costs paid in the long-run. Thus, the PSPRS reform requires that the amortization schedule for new hire unfunded liabilities can be no longer than 10 years. The amortization schedule for the legacy unfunded liabilities of Tiers 1 and 2 was also changed from a rolling period over 20 to 30 years to a closed 20-year schedule. Additionally, the actuarial practice of allowing employers to take contribution holidays during periods of overfunding is now prohibited. This ensures that employers always pay the full normal costs for benefits as they accrue.

Taxpayer/Employer Cost Volatility

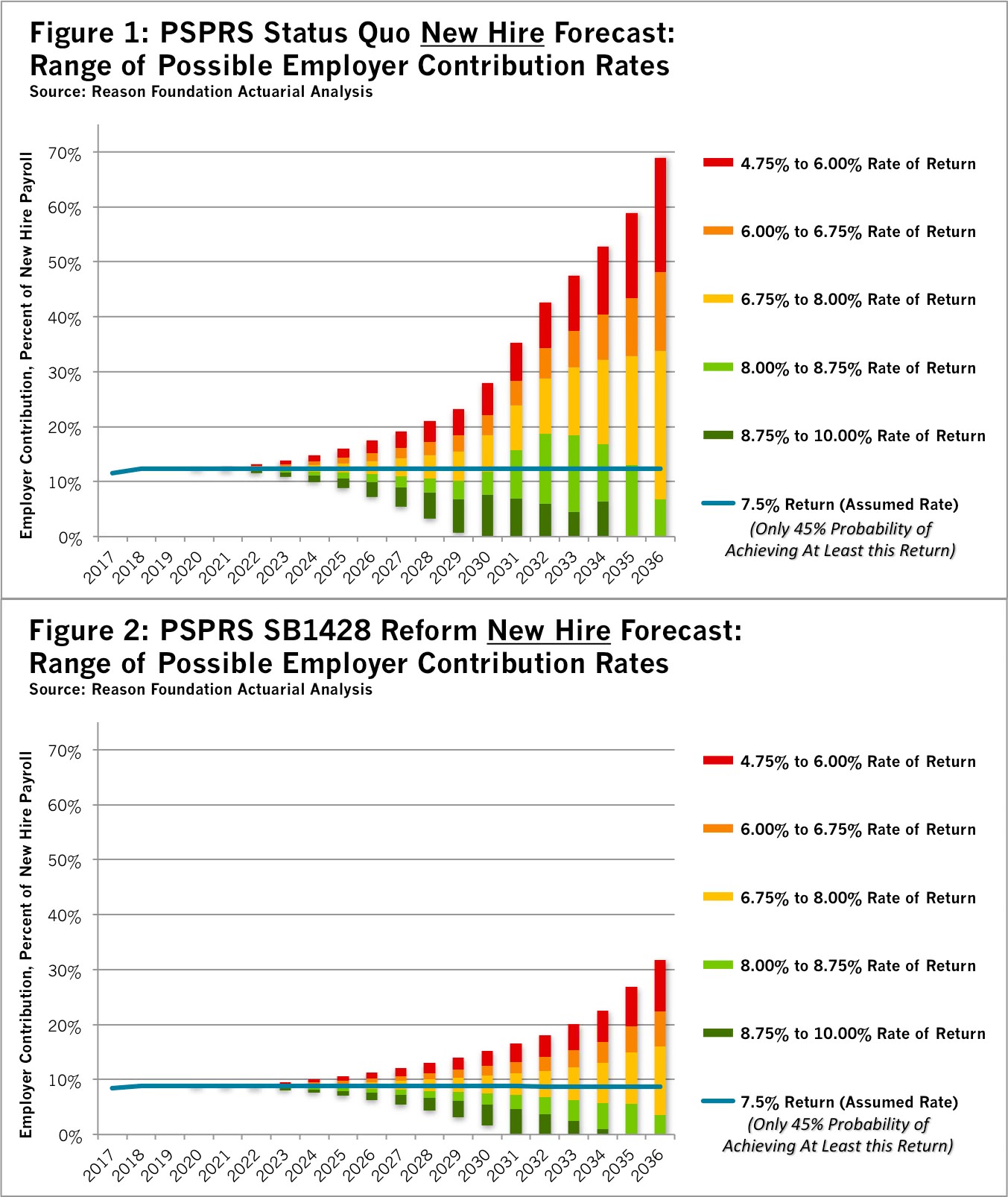

Arizona’s reform of public safety benefits significantly reduces the risks borne by employers—i.e. taxpayers—for providing pension benefits in several different ways.

Second, the equal risk-sharing incentivizes good retirement board decision-making, given the explicit knowledge that working employees have a much lower tolerance for risk and the immediate impacts to take-home pay. We believe this will even further reduce volatility. Combined with the changes to composition of the PSPRS board to include more employee representation, this will change the motivations employees have to consider the risk inherent in particular actuarial assumptions, such as the plan’s assumed rate of return. More conservative actuarial assumptions may increase normal cost (a short-term increase), but decrease the risk of even higher amortization payments (a long-term increase).

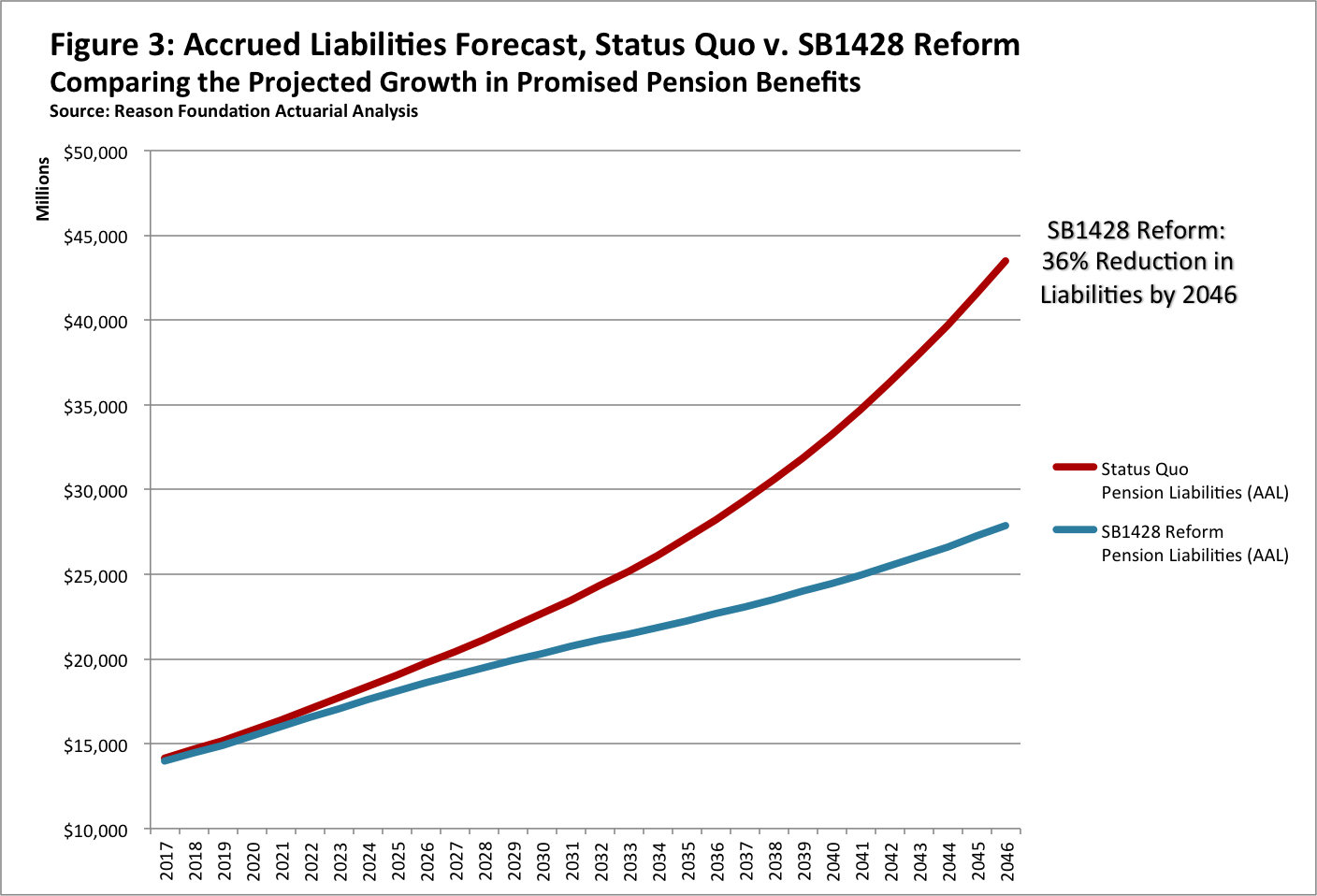

Third, because some employees will select the Defined Contribution Only Plan there will inherently be fewer PSPRS accrued liabilities, i.e. fewer promised pension benefits. In addition, total pension benefits paid will be lower under the reform because of the pensionable pay cap. Thus, the changes adopted with SB1428 lower the trajectory of accrued liabilities relative to making no changes, which will reduce the margin of error for accumulating unfunded liabilities (which are, in principle, the difference between the total value of accrued liabilities and plan assets). Figure 3 below shows a forecast of accrued liabilities pre-reform and after reform.

Post-Retirement Adjustment of Benefits for Current Employees and Retirees

Arizona’s reform fixes a structural problem with how the public safety plan granted post-retirement benefit increases.

Prior to the SB1428 reform, PSPRS employed a Permanent Benefit Increase (PBI) scheme each fiscal year that skimmed assets off the top of good investment returns into a fund to adjust pension benefits in retirement. For retirees hired before January 1, 2012, 50% of PSPRS’s returns over 9% were deemed “excess” and moved to a PBI fund; for retirees hired after January 1, 2012, 50% of returns over 10.5% were captured and shifted into the PBI fund. PBIs were calculated as up to 4% of the average monthly pension benefit in PSPRS for a given year, with the same dollar amount being paid to all retirees regardless of their base monthly benefit.

Not only was the PBI benefit not tied to inflation nor distributed equitably, but the plan relied on the fund’s general assets to pay out this permanent increase to the retirement benefit. Thus, assets might be skimmed off the top of a good market return in one year, used to increase all retirees’ benefit checks by $1,000 the next year, but then the plan’s general assets—which were already handicapped by the PBI skimming—would be required to pay that $1,000 in additional benefit every year afterward. The plan essentially used “one time” windfall money to ratchet up pension checks, creating ongoing costs with no revenue source for these increases.

Two years ago, PSPRS actuaries began requiring employers to make additional normal cost contributions to address the problem of the PBI draining plan assets. These additions to normal cost were charged as if the plan was granting a traditional 2% annual COLA to those hired before January 1, 2012, and a 0.5% annual COLA to those hired after January 1, 2012. However, the PBI charges were not intended to cover the cost of paying out the initial PBI or subsequent PBIs. They were intended to offset the way that the PBI fund skimmed assets off the top of good years of investment returns. In this way, the assets and returns that were intended to pay out base benefits could be at least partially replenished. However, the plan actuary stressed that the amounts charged were not calculated to cover the long-term cost of any particular post-retirement permanent benefit increase. Thus the PBI charge was not really intended to prefund the benefit in the way normal cost will be prefunding the COLA under the SB1428 reform.

As we discussed in a previous article about PSPRS, this toxic mechanism was undermining the solvency of the plan and was a principal reason that the stakeholders in the reform process all came to the table. The new pension laws fix this problem by replacing the PBI with a straightforward cost-of-living adjustment that is prepaid for in normal cost, and is linked to local inflation (the Phoenix-Mesa MSA Consumer Price Index).

The COLA system replaces the PBI for everyone—current retirees, current employees and future hires— and thus has an effect on the forecasted costs of the plan as a whole. The costs of the COLA will be built into regular normal cost payments for current and new hires; meanwhile employers with retirees drawing benefits will be required to make normal cost contributions for retiree COLAs for a full year before COLAs are paid, ensuring the switch to a COLA system does not undermine the current plan assets.

According to the actuarial firm hired by PSPRS, Gabriel, Roeder, Smith & Company (GRS), replacing the PBI with a COLA would mean an increase to normal costs in the short-term (though on net the package of reforms is a cost saver over the long run once the savings of the more affordable new tier are factored in). The reason is that without a change, employers would have been making normal cost contributions as if they were granting a 0.5% COLA; however under the reform COLAs could be up to 2%. The actuarial valuation of the proposed reform assumes that on average the COLAs will be 1.75%, requiring more normal cost contributions than the PBI structure.

This logic is straightforward and fair, but it leaves out the tacit costs of the PBI system—the lost returns from handicapping investments and the drain on plan assets from the unpaid-for permanent increases in benefits that the PBI grants.

Actuarially, replacing the PBI with the COLA is a cost increase in the near-term.

Practically, replacing the PBI with the COLA is a decrease in what taxpayers will have to pay overall for pension benefits. Any near-term increases in costs are simply a financial recognition today of costs that had been deferred to the future. Deferred costs manifest as unfunded liabilities and require a greater amount of contributions to the system than simply prefunding the benefit increases. If the plan had been prepaying for the PBI in the first place, the switch to a COLA wouldn’t necessarily have been a near-term cost increase.

Ultimately, even if the switch from PBI to COLA brings a near-term increase in costs, the price is worth the change to save the solvency of the plan, as promised pension benefits do need to be paid, no matter how high the actuarially determined contribution rates. And in the long run, GRS forecasts that the reform is guaranteed to be cheaper than making no changes because the new tier of benefits has lower costs than the status quo.

Conclusion: “Cost” is Not a Simple Construct

The discussion and debate over SB1428’s fiscal effects emphasizes an important aspect of analyzing the fiscal effects of a major pension reform effort such as what Arizona undertook. “Cost” can take on different meanings. In our view, the ultimate “cost” of pensions is whatever benefit payments are—i.e. how many checks are issued to retirees before they die. The “cost” is not really the actuarially determined contribution rate.

From a budgetary perspective, near-term costs are important. Actuarially determined contribution rates for employers today influence spending priorities for many other policy considerations. And in that sense, near-term “costs” are a real thing. However, when looking at whether a particular reform is improving the solvency of a pension plan, the concept of “cost” should take on a long-term meaning.

A pension plan could reduce its “costs” by adopting irresponsible actuarial assumptions, such as a 10% assumed rate of return or a 5% inflation rate. However, the reduced inflows of monies into the fund in the near term would catch up with the plan in the long run when retirement checks outpace the assets in the plan. The unfunded liabilities would then require the future taxpayers to pay off the pension debt that accrued because of the irresponsible actuarial assumptions used in the past. In this sense, taxpayers today paying the full cost of pension benefits promised to public safety employees working on their behalf today avoids an intergenerational transfer of debt. Just because pension “costs” increase in the near term does not necessarily mean that the promised pensions are more expensive or more generous.

In this case, moving to a prefunded COLA means increasing the amount of normal cost paid for post-retirement benefit adjustments, but that is not an increased cost of benefits as much as an increased budgetary expenditure in the near term to (a) reduce the total taxpayer dollars paid for retirement benefits in the long term, (b) buy down risk and contribution rate volatility, and (c) prevent intergenerational debt transfers.

The PSPRS pension reform is not perfect. Taxpayers still do have some risk exposure. The savings from the reform will be small in the near term and only fully felt over time. And the existing unfunded liability has to be paid down. But the pension reform fixes a significant challenge to PSPRS solvency, and puts the plan on a trajectory toward being better funded and more responsibly governed.

—–

Answers to Frequently Asked Questions About SB1428

Question 1: Since unfunded liabilities are such a big problem, why does this reform not more directly address and reduce PSPRS $6.6 billion in unfunded liabilities?

Answer: During the legislative hearings about SB1428 some critics observed that the reform does not directly eliminate any of the current unfunded liabilities that plague the plan and that are severely affecting municipalities like Prescott and Bisbee. This is true, and a fair observation. However, under Arizona state law there is almost no legal room to make significant changes to benefits for current employees and retirees—thus the actions that would be needed to address current unfunded liabilities were off the table during negotiations.

State courts have struck down most of the benefit changes the Arizona Legislature has attempted since 2010, citing the Arizona constitution’s pension protection clause. Moreover, there is a long history of retroactive benefit reductions being challenged under the federal contracts clause.

Replacing the PBI with the COLA is a change that retroactively modifies benefits, and thus even this element is going to face scrutiny. In order to change post-retirement benefit increases, stakeholders—including public safety labor unions, state legislators, representatives of municipal employers, and the governor’s office—agreed to collectively back an amendment to the Arizona constitution’s pension clause, requiring a ballot measure in May 2016 (Proposition 124). Any other constitutional amendments that might have reduced base benefits were not feasible in the existing political climate.

And even with the collective support for a constitutional change to make this PBI to COLA reform, there are still risks of some employees or retirees bringing a federal contracts clause challenge. The design of the reform was specifically shaped to withstand such a challenge, given that there is a demonstrable public interest in making the change and that the PBI-to-COLA change is really more of an exchange of benefit as opposed to a diminishment of benefit. However, any further changes to already-earned benefits would likely have been found in violation of the contracts clause.

Further, it could be considered unjust to retroactively diminish retiree or current worker benefits that have already been earned. That would be an unnecessarily broken promise when other changes—such as the package of reforms in SB1428—could be adopted to achieve long-term solvency.

Question 2: The forecasted savings of the new benefit tier assumes that the pensionable pay cap grows at 1% a year, but what happens if that assumption is wrong?

Answer: The Public Safety Wage Index is designed to track the weighted average change in the upper limit of pay scales (salary ranges) for public safety positions in a basket of employers specifically designated in state law. This is different than tracking growth of total payroll or average salary. Our own analysis of the change in the upper limit of pay scales over the last decade shows that this change has been approximately 1% annually.

We analyzed the agreements between municipalities and their public safety employees (typically published as memorandums of understanding) where pay scales are detailed, starting with 2006–08 contracts and going through 2014–16 contracts. This timeframe covers both the height of the housing bubble’s tax revenue surge and the fiscally tight years following the financial crisis. And during that timeframe the annualized growth in pay scales averaged 1%, with no three-year time period having greater than 2% annualized growth. This appears to be as good of a historic indicator as we could have for trying to determine a rate to include in the forecast—while naturally having the caveat that the past is not a perfect predictor of the future.

A healthy skepticism of historic data predicting the future would suggest that in fact pay scales are likely to grow more slowly than in the past, because of behavior changes during labor negotiations. Pay scale growth will now have a direct effect on employer and employee normal cost, meaning that during any labor negotiations, the way a pay scale is changed and its relative costs or savings will need to be factored in to any discussions of change in pay. Any increases will come with the tacit agreement by both employers and employees that their joint pension costs will be adjusted relative to the change in pay scales.

Should it turn out that pay scales grow faster than 1%, then liabilities would grow slightly faster than the current forecast; similarly, if pay scales grow more slowly than 1%, then liabilities will grow more slowly than forecast. While there is some sensitivity around this assumption, the costs on either side are not substantial. If, for instance, the PSPRS board wanted to adopt a 2% pensionable pay cap growth assumption to be more conservative, then employers would contribute 1% of payroll more than currently forecast. Tier 3 rates would rise 1% compared to the rates shown in Table 1 above, yet would still be more affordable than the current tier of benefits for every new employee hired.

Question 3: The forecasted reduction in liabilities under the pension reform assumes that 5% of new hires will select the Defined Contribution Only Plan, but is this realistic?

Answer: This is a conservative estimate; the actual percentage to select the DC plan is likely going to be higher than assumed. In Utah, where public safety employees have the option to choose a DC plan that has only two-thirds the benefit of the PSPRS plan (total contribution to the plan 12% vs. 18% in Arizona), roughly 15% a year have chosen the DC Only plan on average since the option was created in 2010.

Affirming the conservatism of this estimate, multiple representatives from Arizona’s public sector labor unions testified that their members will find the DC Only option attractive and that it will make it easier to recruit new members.

The DC Only option will appeal to young new hires who might not want to work 25 years in law enforcement as well as young new hires who want a career in public safety but want the option to move out of state without losing their pension. At the same time, the DC Only option might be preferable for middle-aged hires who want to start a new career in law enforcement (and might already have a 401k from a private sector job). Plus, management-level hires who are brought in from out of state and who don’t intend to work for more than 10 to 15 years as a police or fire chief will likely find it appealing.

Question 4: If the benefits for new hires are more affordable does that mean that the reform cuts pension benefits?

Answer: Full career first responders can receive the same benefit under the reform as current employees. All public safety employees who work at least 25 years in the Defined Benefit Hybrid Plan will receive a 2.5% multiplier, just like today. Plus, for the first time, employees will have choice in selecting their retirement benefit, being able to choose a Defined Contribution Only plan if it better fits their career ambitions, life goals, and retirement lifestyle preference. And, if an employee wants to work fewer than 25 years they can choose to, receiving a lower multiplier that starts at 1.5% with 15 years of service.

The change from a PBI to COLA will influence retirees differently depending on the size of their pension benefit. When there is money to pay PBIs, retirees all get the same fixed amount, a benefit increase up to 4% of the average PSPRS pension benefit. Under the new COLA structure, a benefit increase will be up to 2% of a particular retiree’s pension benefit. For some employees this might mean they receive less in the future, if they have a small pension benefit the PBI would be a higher percentage of their monthly check than retirees with larger benefits. However, replacing the PBI with a COLA is not necessarily a diminished benefit. The PBI was paid out for over twenty years in a row, but the fund has since been depleted. No PBIs were paid last year. Returns in the current year are looking to be well below the assumed rate of return, much less the threshold for “excess” returns, meaning it is unlikely PBIs will be paid next year, or possibly the year after that. The COLA provides more certainty for retirees because they are guaranteed to get a benefit increase every year that there is inflation. No longer will post-retirement benefit increases be linked to good investment returns, which often are unrelated to changes in the cost of living.

Finally, the pensionable pay cap was designed so that it does not influence public safety employees who are first responders, the “line-level” workers who aren’t in the command ranks. Based on the new cap the maximum pension benefit would be $88,000 annually—a combination of the $110,000 cap on pensionable compensation plus the existing limit of benefits to 80% of final average salary. This amount will adjust as Public Safety Wage Index adjusts, but is considered by all stakeholders to be a reasonable annualized pension benefit.

Question 5: The plan’s actuary (GRS) issued a forecast that suggested there is a scenario where costs will be higher under the reform than doing nothing. Is there some risk that the pension reforms of SB1428 might hurt the plan, rather than improve it?

Answer: No, there is no risk that the reform might hurt PSPRS more than it will help. And there are at least three reasons why.

In 2011, the Arizona state legislature passed a law requiring employees to increase their contributions to the plan to help pay down the unfunded liabilities. That law has since been found unconstitutional and is on appeal to the State Supreme Court. If the Arizona Supreme Court upholds the lower court’s ruling, the decision would likely lower most employee contributions by 4% of pay.

However, according to a January 2016 actuarial memo from GRS, if the Arizona State Supreme Court reverses the lower court ruling, then the near-term employer contribution rate requirements would be 6% of payroll higher with the pension reform than if no had been adopted. The GRS actuarial forecast found that over time pension reform would be 4% of payroll cheaper in this same scenario, but that in the early years of reform replacing the PBI with a COLA would be more expensive than the savings from adopting a more affordable tier of benefits.

Here are the three reasons why this scenario does not pose a risk to PSPRS even under the SB1428 reform:

- First, the baseline forecast in the GRS report is based on the already underpriced cost of the PBI. Actuarially speaking, the switch from a PBI to the COLA might entail an increase in employer contribution rates—but that doesn’t mean the switch is increasing the cost of benefits so much as shifting when those costs will have to be paid (from the future when the PBIs are issued to the present to prefund the COLA). In the long run, prefunding the COLA will mean lower total costs because the PBI payments won’t be degrading the solvency of the fund and generating unfunded liability interest costs.

- Second, the probability that the near-term costs will be higher under reform rather than doing nothing is very low. In order for the scenario laid out by GRS to become true, all of the following would have to happen: market valued returns would have to stay below 9% every single year for the next 20 years (almost a 0% chance), the average rate of return would have to be 7.5% over the same 20 years (about a 45% chance), and the State Supreme Court would have to reverse a lower court ruling.

- And third, even if this particular scenario were to occur and near-term costs under the reform were higher than leaving the PBI in place, that does not mean the SB1428 reform would hurt the plan. It simply means that taxpayers needed to pay down some of the risk they were carrying with the structurally unsound PBI system, and the state legislature responsibly chose to do so.

Additional Resources:

- For more information about the Arizona pension reform, see our overview of SB1428

- Reason Foundation’s Analysis of Proposed PSPRS Pension Reform (.pdf)

- Arizona Senate Finance Committee testimony by Reason Foundation’s Pete Constant

- Full text and legislative history: Senate Bill 1428 | Senate Bill 1429 | Senate Concurrent Resolution 1019

- Arizona Auditor General, Performance Audit and Sunset Review of the Public Safety Personnel Retirement System (Report No. 15-111, September 2015)

Anthony Randazzo is director of economic research at Reason Foundation. Leonard Gilroy is director of government reform at Reason Foundation. Pete Constant is director of Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.