- Lessons from the Maryland Key Bridge collapse

- Texas plans takeover of P3 toll project in Houston

- The real challenge facing EPA’s new electric vehicle regulation

- I-15 express lanes project survives attempted cancellation

- Freeway driving and political opposition will test automated vehicles

- Time to rein in federal funding for non-cost-effective transit projects

- News Notes

- Quotable Quotes

Lessons from the Maryland Key Bridge Collapse

The collapse of Maryland’s Francis Scott Key Bridge should be a wake-up call, not only for America’s highway and bridge owners/operators but also for the international maritime industry.

By now, it’s widely known that the Maryland Transportation Authority, owner/operator of this 1977 toll bridge, failed to absorb the lesson of the 1980 collapse of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge in Tampa, Florida, following a collision with a 580-ft.-long freighter called Summit Venture. Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) replaced the aging truss bridge with a cable-stayed bridge and added large concrete “dolphins” to protect its piers from collisions with ships.

In 1991, the American Association of State Highway & Transportation Officials (AASHTO) released guidelines for major river bridges, which called for dolphins, among other safety measures. There is no evidence that the Maryland Transportation Authority ever seriously considered retrofitting dolphins to the Key Bridge. That’s odd. Because in the same Patapsco River, a state agency added dolphins to protect new electrical transmission lines. And, today, the Delaware River & Bridge Authority is spending $95 million to add dolphins to its Delaware Memorial Bridge, serving Philadelphia’s port. They will be 80-ft.-diameter steel caissons filled with crushed rock. Compared with the costs of losing and replacing such a bridge, this appears to be a prudent investment.

I’m not a maritime engineer, so I cannot comment on whether dolphins of that size would stop or deflect one of today’s huge container ships. But here is how the Dali that hit the Key Bridge compares with the Summit Venture (Sunshine Skyway) and two of today’s largest container ships.

| Ship | Size | Length | Width |

| Summit Venture | 19.7K tons | 580 ft. | 86 ft. |

| Dali | 10K TEUs | 934 ft. | 160 ft. |

| Ever Given | 20K TEUs | 1312 ft. | 190 ft. |

| Irina | 24K TEUs | 1312 ft. | 210 ft. |

As you can see from the table, the Dali is smaller than the Ever Given (which got stuck in the Suez Canal) and the world’s current largest container ship, the Irina. Whether dolphins of the kind used on other bridges would be effective against today’s huge container ships remains to be seen. If they are not, other measures should be considered, such as requiring tugs to guide ships until they are safely past any harbor bridges. That’s a controversial topic in the maritime industry due to the cost, but bridge collapses are extremely expensive as we’ll be finding out in the aftermath of the Dali-bridge collision.

Who should pay for the Key Bridge’s replacement?

President Joe Biden jumped the gun by declaring that the federal government would foot the entire bill. That ignores a number of key points, including that the Key Bridge is a toll bridge whose replacement should be financed at least in part via toll revenue bonds. It also ignores a $350 million Maryland insurance policy on the bridge and ship insurance provided by Britannia P&I Club, one of about a dozen such insurance vehicles, according to The Wall Street Journal. These clubs pool their resources in the event of a major disaster, and up to $3.1 billion is available per ship. President Biden’s hasty over-reaction has drawn some bipartisan opposition, including from Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Rep. John Garamendi (D-CA). Rep. Garamendi told Bloomberg TV, “I don’t think this has to be federal taxpayer money. Let’s first go to the insurance side of it, and then we’ll see what’s left over.”

It’s far too early to put a price tag on the replacement bridge. The original Key Bridge cost only $316 million, but its flawed design must not be replicated. Its truss structure is “fracture critical,” meaning that if one structural element fails, the whole thing collapses. Only 2.8% of America’s bridges are fracture critical, but they include a number of major river-crossing bridges.

Since a whole new bridge will have to be designed, other decisions will have to be made: how high above the river, how many lanes, etc.—in addition, presumably, to dolphins and/or other safety measures.

Finally, let’s think about standards for ocean-going mega-ships. Dali, like nearly all container ships, was powered by a single diesel engine. When it failed, the ship lost motive power and electricity. This kind of single-point failure would never be allowed in an airliner. And that raises troubling questions about design and operating standards for major ocean-going ships. There seems to be no institutional safety certification and operational regulation as is standard worldwide in aviation. The International Maritime Organization issues “guidelines and recommendations” for national governments to consider, but there is no enforcement—in sharp contrast to international aviation.

While devising new institutions would be very complicated, there is a plausible alternative: maritime insurers. They bear the costs of disasters such as the destruction of the Key Bridge by a container ship. If any entity might be motivated to insist on more rigorous standards for ship design and operation, it’s maritime insurers. Let’s hope they take this catastrophe seriously.

Texas Plans Takeover of P3 Toll Project

In a move that surprised transportation experts, on March 28 the Texas Transportation Commission voted to begin planning the termination of a 52-year public-private partnership agreement under which private investors financed the addition of express toll lanes to 10 miles of Texas State Highway 288 in the Houston metro area. If the plan is implemented, the state will create a non-profit corporation (similar to the one responsible for the Grand Parkway—an emerging outer ring road in that part of Texas) that would issue bonds to finance the take-over.

The Texas public-private partnership law refers to such projects as comprehensive development agreements, or CDAs. The CDA for SH 288 was signed in 2016 and the project was opened to traffic in 2020. Like many design-build-finance-operate-maintain (DBFOM) public-private partnerships, the comprehensive development agreement for this project includes two forms of early termination—either for convenience (with compensation) or for cause (with no compensation). Since the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has no cause for termination, the compensation that will be provided is based on a complicated set of provisions in the long-term CDA. By TxDOT’s calculations, this amount is likely to be $1.73 billion.

My research into this unexpected development found that the idea originated within TxDOT, rather than from anti-P3 legislators. In a private message prior to the commission meeting, I was told that being able to buy the project back for around $1.7 billion would, in effect, be a bargain since the concessionaire’s own valuation is significantly higher. Also, this would give TxDOT more flexibility to, for example, add general-purpose lanes to the corridor. In addition, the state would gain control of the variable toll rates.

After the unanimous vote, Commission Chairman Bruce Bugg noted that the vote itself does not change the CDA but authorizes TxDOT Executive Director Marc Williams “to take further action if it is determined to be in the best interests of the state of Texas.”

In an article in the March 2024 issue of Public Works Financing, Michael Bennon notes that, “A buyout by TxDOT is certainly not a foregone conclusion…TxDOT will now initiate negotiations with [the P3 company] in the coming months to negotiate some concession modifications in lieu of a buyback and all the transition costs that would entail.”

I hope he’s right.

In my testimony at the commission meeting, delivered by a Reason Foundation colleague, I explained my assessment of the TxDOT proposal this way:

“Our message is that terminating the SH 288 comprehensive development agreement would be unwise, with long-term consequences for Texas’ highway infrastructure.

Twenty years ago, Texas pioneered long-term design-build-finance-operate-maintain public-private partnerships. The result was $9.3 billion of new highway capacity, of which only 16% was funded directly from taxpayers.

The Texas model was so successful that six other fast-growing states adopted it: Colorado, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. They all compete with Texas for new and expanded businesses and they can now expand their highways at 16 cents on the dollar, as Texas used to. Cities like Atlanta and Nashville are also currently developing comprehensive toll lane networks to reduce traffic congestion.

These express toll lanes have produced large benefits for motorists, truckers, and bus riders in every state where they operate. Motorists have a congestion-free travel option, truckers benefit from increased capacity, and bus riders have a virtual exclusive guideway providing faster, more-reliable transit service.

Investors in these projects include public pension funds, insurance companies, and infrastructure investment funds. Nationwide, over $63 billion has been invested in long-term transportation infrastructure projects in recent decades. Nearly all the express toll lanes projects have investment-grade ratings, including SH 288.

To compete with other fast-growing states, Texas needs more express toll lanes. Priorities should include:

- Finishing the planned network in the Dallas-Ft. Worth metroplex;

- Developing a network in the Houston metro area; and,

- Adding express toll lanes instead of high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes on I-35 in Austin and San Antonio.

If the I-35 projects were constructed as CDAs, instead of costing TxDOT $8 billion, the state would likely need to put in only about 15%, freeing up as much as $6.8 billion for non-CDA roadway projects in other areas of the state: urban, suburban, and rural.

Terminating the SH 288 CDA would send a message to investors: your money is not welcome here. Instead, investors will choose Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.”

The Real Challenge Facing EPA’s New EV Rule

Most environmental groups cheered last month’s release of a slightly modified Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) vehicle emissions regulation that will require that 68% of new vehicles sold in 2032 be electric (55% battery electric and another 13% as plug-in hybrids). So did most auto companies, relieved by a bit of slack introduced in the schedule between now and 2032. The cheering was far from unanimous, however. Many conservatives and Republicans blasted the regulation as forcing Americans to buy cars they don’t want.

Even some prominent Democrats took issue with the plan. Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) said, “This really isn’t where the American people are at. Sales [of EVs] continue to drop, and a lot of people are wary of the direction.”

Retiring Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) released a statement saying, “The federal government has no authority and no right to mandate what type of car or truck Americans can purchase.”

There may or may not be grounds for litigation over whether the regulation is within EPA’s power. A possible indicator is a March 27 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas that a Federal Highway Administration regulation that state transportation departments must measure the greenhouse gas emissions of vehicles using their highways is beyond what Congress authorized and therefore void.

But there’s a more substantive problem with the new EPA regulation: lack of sufficient electricity for this rapid transition to electric vehicles. A March 7 article in The Washington Post was headlined, “Amid Explosive Demand, America Is Running Out of Power.”

It focused on recent upward revisions in electricity demand due to the continued increase in online data storage and the huge new growth in electricity use for developing artificial intelligence (AI). Among the examples in the article, “Northern Virginia needs the equivalent of several large nuclear power plants [just] to serve all the new data centers planned and under construction. Texas, where electricity shortages are already routine on hot summer days, faces the same dilemma.”

And there is also the increasing use of electricity for crypto mining.

Analysts at the National Center for Energy Analytics (NCEA) cite an Energy Department study estimating that the electricity infrastructure needed to support EVs representing 10% of all personal vehicles would cost $50-$125 billion. In a March 27 Wall Street Journal op-ed, NCEA’s Jonathan Lesser and Mark Mills estimate that achieving EPA’s new EV goal will require more than $1 trillion in grid updates by 2035. That is not going to happen.

What about electrifying trucks in addition to cars? A study released in March by consulting firm Roland Berger (funded by the Clean Freight Coalition) estimates that electrifying medium and heavy trucking would cost close to $1 trillion. That breaks down as $620 billion investment by fleets and charger operators and another $370 billion by utilities to upgrade the electricity grid. As American Trucking Associations CEO Chris Spear noted, “What Roland Berger’s study shows is that this mad dash to zero [emissions] exposes the supply chain to a $1 trillion unfunded mandate. This is not included in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.”

One caveat about this study is that it assumes a battery electric model for all heavy trucks, despite studies showing that hydrogen fuel cell propulsion is a much better fit for long-distance Class 8 trucks.

The underlying fallacy of the reigning “electrify everything” model is that it tries to do far too much within the next two or three decades. On the one hand, a major priority is to eliminate all fossil fuel (coal and gas) electricity generation, which means replacing about 61% of all current generation with solar, wind, and nuclear. The existing regulatory structure makes that impossible over such a short time frame. In addition, the idea is to replace fossil fuels in all surface transportation, home heating and cooling, steel-making, and many other industries. Along with the robust projected growth of data centers, etc., all of this will likely add up to at least doubling electricity demand over the same several decades. Also required for this vision to become reality is a huge expansion of long-distance electricity transmission, and substantial upgrades of local electricity substations. (See “Rethinking U.S. Electrification Strategy” in the June 2023 issue of this newsletter.)

In short, EPA’s new vehicle regulations are part of an impossible ‘electrify everything’ dream that cannot be achieved over the next several decades. Once this sinks in, EPA’s new regulations will have to be changed.

I-15 Express Lane Project Survives Environmental Attack

A new link in the greater Los Angeles express toll lanes (ETL) network survived an 11th-hour challenge from environmental groups in February. The project will close a gap in the emerging ETL network in Riverside and San Bernardino Counties, a region generally known as the Inland Empire. Express toll lanes are already in operation on north-south I-15 in Riverside County and are under way on east-west I-10 in San Bernardino County. But, because the Inland Empire is home to numerous warehouses and distribution centers dealing with containers from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, I-15 has become a very truck-intensive corridor for trucks departing the Inland Empire for points north and east of California.

And that led to a serious effort to cancel this project before it received final approval from the California Transportation Commission (CTC). Opponents argued that added capacity for that stretch of I-15 would induce demand for even more trucks to use I-15, worsening the effects of diesel exhaust on residential areas in the vicinity of the freeway. Proponents of the express lanes pointed out that there was little room left in the region for additional warehouses. They also pointed out that the trucks in question have no realistic alternative to I-15, to carry out their important role in interstate commerce.

Fortunately, the CTC ended up voting 9 to 1 to approve the project. But this episode is an example of how too many debates on transportation improvements focus mostly or entirely on local impacts while ignoring regional and national benefits. Cutting out eight miles of what is becoming a multi-county express toll lanes network serves no useful purpose. The diesel emissions from those long-haul trucks on I-15 would still be there over the next decade or two, until state and federal emission requirements lead to those trucks’ replacement by battery-electric or hydrogen fuel cell trucks.

Highway investments, such as adding express toll lanes to congested freeways, are long-term, and will have long-term benefits for personal vehicle commuters and bus transit commuters (assuming local transit agencies have the smarts to take advantage of the ETL network’s mostly uncongested lanes). The long-term benefits will far exceed the costs of filling in this eight-mile missing link in the metro area’s express toll lanes network.

Freeway Driving and Political Opposition Will Test Autonomous Vehicles

By Marc Scribner

Over the last decade, automated vehicles (AVs) have been undergoing testing on public roadways throughout the country. AVs deployed as urban robo-taxis and driverless freight delivery have largely been confined to low-speed surface streets. Autonomous trucks that aim to provide medium- and long-haul freight service between distribution centers have been operating with trained drivers behind the wheel. This year, companies developing AVs for both the robo-taxi and freight markets have their eyes on high-speed freeway deployments. AV freeway operations are necessary for commercial viability but may face substantial barriers arising from misguided policy proposals.

In March, The Wall Street Journal published an article by reporters Meghan Babrowsky and Miles Kruppa on AV companies’ near-term plans for freeway deployments. They note that Google’s sister company Waymo has recently begun testing driverless operations on Phoenix-area freeways. Freeway access is viewed as critical to success in Los Angeles, which Waymo estimates to be a $2 billion robo-taxi market, according to the Journal’s reporting.

The company has yet to begin these operations in California but has secured the necessary regulatory authorizations to do so. On Jan. 11, the California Department of Motor Vehicles, which regulates AV safety in the state, approved Waymo’s expanded operational design domain to include freeway operations in portions of the Los Angeles and San Francisco metro areas at speeds of up to 65 miles per hour. On March 1, the California Public Utilities Commission, the economic regulator of robo-taxis, approved Waymo’s updated passenger safety plan to allow commercial operations that mirrors the earlier DMV safety approval.

On the commercial freight side, most industry interest is currently centered in Texas. The Journal highlights Aurora’s plan to launch driverless trucks later this year on I-45 between Dallas and Houston. Aurora is not alone. I noted in the January edition of this newsletter that Kodiak Robotics has a similar deployment plan and timeline for the lucrative east-central Texas corridor. In addition, “middle-mile” business-to-business AV truck developer Gatik also plans to launch driver-out operations in 2024.

Freeway driving offers substantially higher speeds. In a January blog post announcing its freeway driving expansion plans, Waymo compared routes between Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport and northern Scottsdale, showing that freeway access could reduce trip time by half. Travel on surface streets was estimated to take 50 minutes versus 25 minutes when Waymo vehicles were able use to the Loop 101 freeway.

I can confirm this is accurate from personal experience. In November, I took a 14.1-mile Waymo One trip from Sky Harbor Airport to the edge of the service boundary in northern Scottsdale. The trip time was 40 minutes because the Waymo vehicle took only surface streets with a maximum speed limit of 45 miles per hour. My return trip in a conventional human-driven Uber took 23 minutes thanks to using the freeway with a 65-mph speed limit. While I enjoyed my Waymo trip, commercial viability surely cannot be based on the novelty of being chauffeured with no one behind the wheel.

Despite the high speeds, urban freeway driving is generally the safest. The controlled-access design of freeways limits conflicts with other vehicles and pedestrians, which greatly reduces the frequency of dangerous crashes. The Bureau of Transportation Statistics reports that in 2021, urban Interstates experienced 0.66 crash fatalities per 100 million vehicle-miles traveled. This compares to fatality rates of 1.51 for non-Interstate urban arterials (which includes some controlled-access freeways, but many more that are not), 1.41 for urban collector roads, and 0.84 for local urban streets.

The safety and economic cases for AV freeway driving are clear. However, misguided policy threatens to limit the benefits from these operations. The most serious threat comes from California lawmakers, where Senate Transportation Committee Chair Dave Cortese has introduced Senate Bill 915, which would require AV companies to receive prior approval to operate in each of California’s cities and counties. In essence, it would replace California’s uniform statewide AV regulatory regime with 540 local AV regulators.

While ostensibly constructed to “prioritize local control in the decision to deploy autonomous vehicle services,” SB 915 is part of a package of bills being spearheaded by organized labor, including another attempt to outlaw driverless operations of heavy-duty AV trucks following California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s veto of Assembly Bill 316 last year. Unions representing drivers have made no secret that their motivation is to, in their words, prevent AVs from “killing jobs through automation.”

Anyone concerned about road safety and economic opportunity should be alarmed by this legislation. A balkanized regulatory landscape would upend the economics of AVs and thereby prevent the realization of the safety, personal convenience, and business benefits of AVs. While it is true that California is but one state of 50, it wields outsized influence in both economic and political affairs in the United States.

Passage of California SB 915 might not spell nationwide doom of AVs by itself, but similar legislation would inevitably be introduced in other union-dominated states if it succeeds. The unworkable patchwork of state AV laws long feared by technology developers may be taking root just as AV companies are turning their attention to commercial viability.

Time to Rein in Federal Funding for Non-Cost-Effective Transit Projects

By Baruch Feigenbaum

In the March 18 edition of Eno Transportation Weekly, Jeff Davis had the unenviable task of sorting through projects in the Federal Transit Administration’s Capital Investment Grant (CIG) pipeline. CIG is the administration’s largest discretionary grant program.

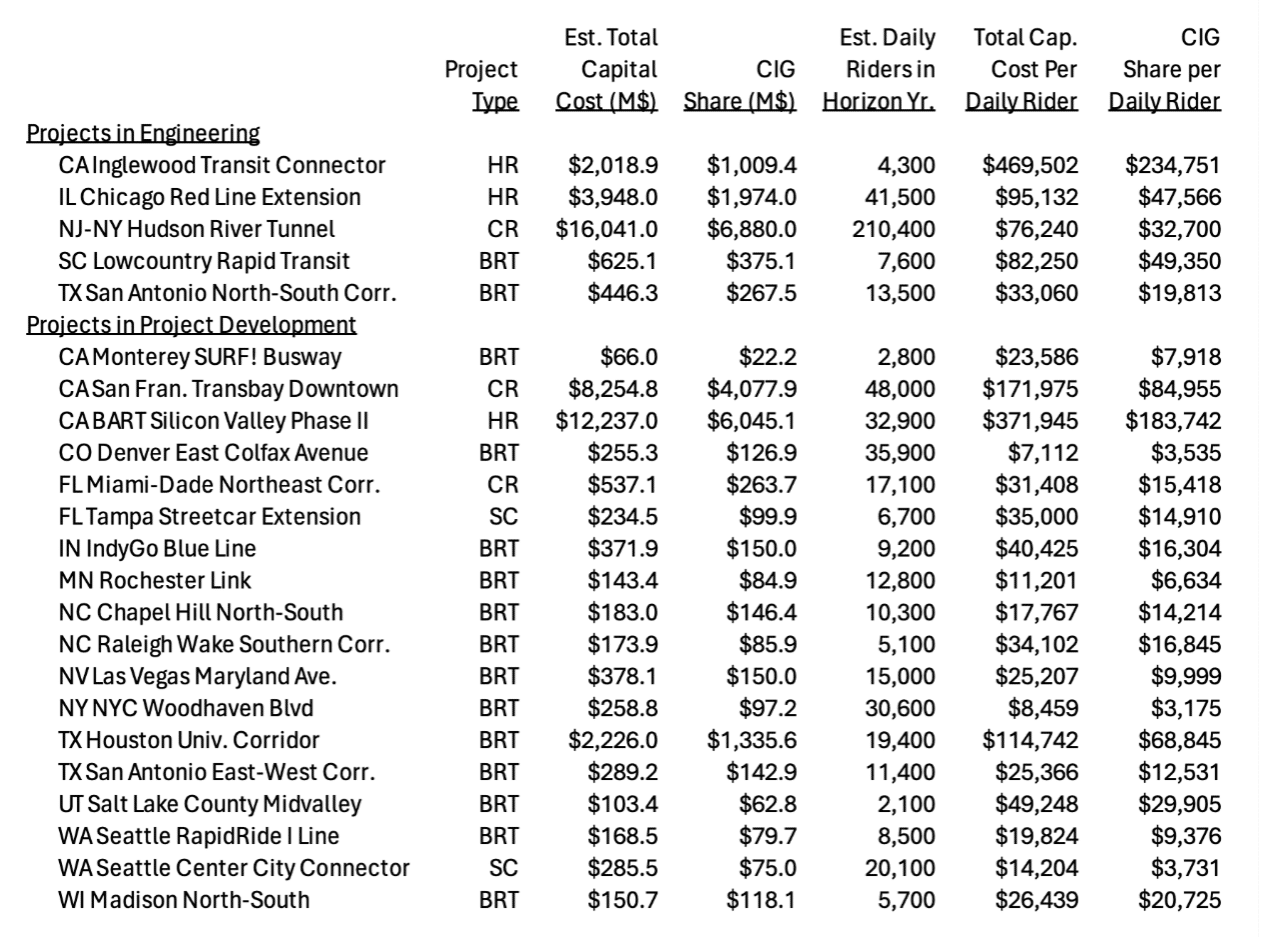

President Joe Biden’s 2025 federal budget request detailed 23 projects: 18 in project development and five in engineering. As Table 1 shows, three of the projects are heavy rail transit (HR), three are commuter rail (CR), two are streetcar, and 15 are bus rapid transit (BRT) projects.

Table 1: President’s FY 2025 Transit Projects

Source: Eno Transportation Weekly

While there are five columns of figures in the table, the Capital Investment Grant share per daily rider is the most important measure of cost-effectiveness. Some projects are going to cost more because of project type or because they are located in a high-cost area. Some will have fewer riders because they are located in a metro area with fewer people. Only total capital cost and CIG share factor in cost and ridership to determine cost per daily rider and only CIG share per daily rider is a federal cost paid directly by taxpayers. Therefore, the rest of this piece focuses on the share per daily rider metric.

Before I get to the bad news, I want to focus on the big positive of the recent grants: a majority of the projects are bus rapid transit. Federal Transit Administration (FTA) doesn’t break them out into types, but they look to be a mix of bus rapid transit heavy (dedicated running way) and BRT lite (shared running way). Ten years ago many considered bus rapid transit a consolation prize. Yet BRT is both high-quality and cost-effective. Two BRT projects had a CIG share of less than $4,000 per rider; the average BRT CIG is $19,277, lower than all modes except streetcar, which has a CIG or $9,320. Meanwhile, commuter rail’s average CIG was $44,358, and heavy rail’s average was $155,353 per rider.

Why is heavy rail transit’s (HRT) average so stratospheric? And what can policymakers do to avoid funding future white elephant projects? Two exceptionally expensive HRT projects inflate the HRT total: the Inglewood Transit Connector in Los Angeles and the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Silicon Valley Phase II Project.

The Inglewood Transit Connector links the new National Football League (NFL) Rams and Chargers stadium to the Metro K Line. While it is billed as supporting the working class, its chief beneficiary is Stan Kroenke, who owns the NFL stadium, as well as the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic committee, which plans to host the opening ceremony in the stadium.

Silicon Valley Phase Two extends the BART line from the Berryessa Center into San Jose and then into the city of Santa Clara. San Jose has an existing LRT that has one of the worst cost-benefit ratios in the country. It’s not clear why this BART extension is needed, and if transit is needed, why heavy rail is the best solution.

These types of projects are problematic for both taxpayers and transit advocates. For taxpayers, spending well over $200,000 per daily rider is an exorbitant amount of money. There are plenty of more pressing transportation needs throughout the country. If we cannot find a better use of funding, maybe the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) allocated too much money. It would be cheaper to buy riders a personal vehicle than to fund these projects.

But the problem may be even worse for other transit agencies. These gold-plated heavy rail lines are sucking up much of the potential funding. Consider all of the BRT lines that could be built around the country, for just the cost of the Los Angeles project.

Given that costs for the most expensive projects keep spiraling, we need to make one of two changes in transit policy. The first would be to eliminate all federal transit construction subsidies and provide operating subsidies instead. The regions that really need these large capital projects have the local (and in many cases state) funding to build them. Transit is inherently a regional service, not a federal one. Further, with state funding, agencies would not be subject to federal red tape such as Buy America and Davis-Bacon. And several studies have shown that with less money, projects would be less subject to cost escalation from controllable factors such as labor costs and project management. But that action would require agreement between Congress and the presidential administration in the next surface transportation reauthorization, which is two years away. And there is no guarantee that Congress and the Administration will agree on anything.

That leaves us with option two: set a cap on federal funding of CIG per daily rider. I would recommend an average of $100,000. That would allow every project, except for the two California rail projects noted above, to be funded. Since construction costs vary by region, the cap might be higher in Los Angeles than it is in Wichita. The federal government already calculates differential salaries for its employees, so it is not a stretch to calculate that same difference in construction costs. Projects that exceeded the cap would still be funded at the cap, but no higher. And if Los Angeles thinks it’s really that important to build the Inglewood Transit Connector, the cities, regions, and state can be the ones footing the bill.

Setting a cap to rein in exorbitant transit spending would be a small step. But it would be a step in the right direction.

Michigan Legislature Looks into Tolling and/or Mileage Charges

Last month the Michigan Infrastructure & Transportation Association released a report estimating that the state is short $3.9 billion per year to properly maintain its aging highways. At a hearing on March 8, the House budget committee heard testimony from Ron Davis of HNTB about their 2023 study that found that 14 of Michigan’s 31 major highways could be rebuilt and properly maintained via tolling. Subsequent testimony from Patricia Hendren of the Eastern Transportation Commission summarized the case for phasing out fuel taxes and replacing them with per-mile charges. It is unclear when the legislators will make a decision on future highway funding.

EPA Releases Emission Regulations for Trucks

Late in March the Environmental Protection Agency issued new emissions regulations for trucks, ranging from delivery vans and garbage trucks up to Class 8 big-rigs. Reg. 2060-AV50 is a companion to the previously released emission regulations for light vehicles (cars, SUVs, pick-up trucks) unveiled by EPA earlier in in March. The truck regulations have been harshly criticized by trucking organizations American Trucking Associations and Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association as “entirely unachievable [post-2030] given the current state of zero-emission technology, the lack of charging infrastructure, and restrictions on the power grid.”

Florida Opens the Door to New P3s

The legislative session that ended in March yielded an expansion of potential long-term DBFOM public-private partnerships in Florida. House Bill 781, passed unanimously by the House, provides new procedures for accepting unsolicited proposals. And HB 287 allows for user-fee-financed highway projects to have concession lengths of up to 75 years. Florida has not yet approved any revenue-financed highway P3s, but the revised P3 legislation (in which P3s are termed somprehensive agreements) gives new visibility to this option.

More EV Startups May File for Bankruptcy

A full-page article in The Wall Street Journal shows annual losses for EV startup companies Polestar, Fisker, Vinfast, Lucid, and Rivian, with most at least appearing close to running out of cash. The article notes that both Lordstown Motors and Arrival have already gone bankrupt, and reporter Sean McLain explains that these companies “are burning through their cash reserves as they spend heavily on expanding factory production and sales—all while losing money on every vehicle they sell.”

Another Freeway Capping Planned

Transportation planners in Detroit are planning to put a five-acre cap over a stretch of below-grade freeway I-75 to reconnect neighborhoods that were split when the freeway was built decades ago. The section extends from Cass Avenue to Brush Street. No cost estimate is available for the project, but it has received a $2 million federal study grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities program. Further along is an earlier project to cap an area of I-375 near Lafayette Park. The I-75 Overbuild project would provide mostly green space to reconnect communities on either side of that freeway.

License Plate Fraud Plaguing Toll Facilities

Cheating on tolls is a big enough problem to make the front page of The Wall Street Journal. The problem is primarily with those who don’t have transponders, whose license plates must be read in order to send a bill for the toll. Violators steal service by using a black-market temporary plate, defacing the license plate so it is not accurately readable, installing a cover that can be lowered over the plate when nearing a toll gantry, or installing a $220 license plate flipper. Dallas and San Francisco agencies reported $33 million in uncollectable tolls last year; the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority reported a $21 million loss. Unless stricter enforcement and/or higher penalties can be implemented, license-plate tolling may have to be reconsidered.

DOT Grants Available for P3 Project Planning

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included funds for a new Innovative Finance and Asset Concessions grant program. Its purpose is to assist state and local governments unfamiliar with P3 projects to identify assets or facilities that could be replaced or upgraded via a long-term P3 concession. Technical assistance grants can be used to contract with technical, financial, or legal advisors. Expert services grants would be used to contract with experts to “explore leveraging public and private funding” in connection with a specific existing asset—aka “infrastructure asset recycling.”

Louisiana P3 Expert Joins WSP

Infralogic reports that Shawn Wilson, former secretary of the Louisiana Department of Transportation & Development, has joined consulting firm WSP as senior vice president and national agency coordination leader for transportation and infrastructure. At the Louisiana agency, Wilson launched revenue-risk P3 projects, beginning with the Belle Chasse Bridge replacement and continuing with the recently approved Calcasieu Bridge replacement. Wilson says part of his role at WSP will be to advise transportation agencies on P3s and to help the company develop P3 best practices.

European Safety Expert Wants Cars to Have Physical Controls

Matthew Avery, director of strategic development at Euro NCAP, which evaluates the safety of new cars, sees a major problem with the trend of putting practically everything on dashboard touch screens. Having to find the right control on the screen “obliges drivers to take their eyes off the road, raising the risk of distraction crashes.” Euro NCAP in its tests in 2026 will encourage manufacturers to use separate physical controls for basic functions such as turn signals, hazard lights, horn, windshield wipers, and any SOS features. So far, Euro NCAP’s U.S. counterpart—the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety—has not focused on this problem.

Genoa Getting $1.1 Billion Port Tunnel

World Highways reports that construction has begun on a 22.1-mile tunnel beneath the city’s port. The two-tube tunnel will connect the east and west parts of Genoa. The bored tubes will be the largest-diameter road tunnels in Europe. The tunnel is being built for toll road company Autostrade per l’Italia. The planned opening date is in the third quarter of 2029.

TransJamaican Highway Gets a Toll Rating Upgrade

Fitch Ratings has upgraded the senior secured notes from BB- to BB, reports Infralogic. The rating reflects the stability and resiliency of a commuting tollway serving the capital city of Kingston. Toll rates can be adjusted annually based on U.S. inflation and the exchange rate between the Jamaican and U.S. dollars.

Oklahoma Converts Two Turnpikes to Interstates

Last month the Oklahoma Turnpike announced that two of its facilities have become part of the Interstate highway system. The Kilpatrick Turnpike around the western part of Oklahoma City is becoming I-344. And the Kickapoo Turnpike, which links I-40 and I-4 east of the city, will now be I-335. All the system’s toll roads will have been converted to cashless operation by the end of this year.

San Francisco Proceeding with Bus Yard P3

On March 5, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved a measure to proceed with the Potrero Yard Bus Yard Modernization P3 project. Predevelopment work has been under way since Nov. 2022 by the consortium led by Plenary. The mixed-use project will include construction of a three-story bus storage and maintenance project plus 500 units of affordable housing on the site.

Feedback on Aerial Tramway Article

Reader John Ellis reports that there is at least one aerial tramway with a gondola capacity of 28 people. It’s located at the Palisades Tahoe (formerly Squaw Valley) ski resort. It can transport up to 4,000 people/hour at a speed of 14 mph. “It’s great as a ski lift, but hardly seems practical for most cities, as you wrote,” Ellis noted.

Feedback on EV-to-Home Electricity

Reader Ian Myles in Australia reports that his Nissan Leaf can transmit electricity to his house, “but the charging infrastructure is expensive and grid operators are still trialing it.” He says that for his air-conditioned house, the car battery could run it for about one day.

Sobering Thoughts on Government Picking Winners

Reason magazine reporter Joe Lancaster looked into the economics of five government-funded transportation infrastructure projects, in an article in the February issue: the GM IT Innovation Center (Chandler, AZ), Lordstown Motors (Lordstown, OH), Tesla and SolarCity (Buffalo, NY), Yellow Corporation (Overland Park, KS), and Amazon HQ (Arlington, VA). None of these examples of 21st-century industrial policy turned out well. See “The Government Is Better at Picking Losers than Winners,” Reason, Feb. 2024.

“Climate change over the rest of this century will make the world marginally hotter almost everywhere. It will make some weather events such as extreme rainfall more intense than they otherwise would be. And it will result in some other extremes being more frequent or intense in some parts of the world and less so in others. But it will not shift the basic functions of the Earth system into a profoundly different state, one that human societies are entirely unfamiliar with or create weather extremes far outside the range of extremes that human societies have dealt with in various geographies that they have long inhabited.”

—Ted Nordhaus, “Did Exxon Make It Rain Today?” The New Atlantis, Winter 2024

“Instead of the anticipated surge, total [U.S.] infrastructure spending has fallen by more than 10% in real terms since the passage of the [Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act] law. The single biggest component of the infrastructure package was a 50% increase in funding for highways to $350 billion over five years. But highway construction costs soared by more than 50% from the end of 2020 to the start of 2023, in effect wiping out the extra funding.”

—“Infrastructure Weak,” The Economist, Nov. 25, 2023

“It turns out there’s a big difference between selling an EV to a gung-ho early adopters and getting everyone else to make the switch from gas. Early adopters tend to be affluent and thus can afford the higher sticker price and insurance costs. So affluent, in fact, that most of those early adopters also own a gas-powered vehicle, which helps allay one of the most pressing concerns people have about buying an EV: How do I charge it? Charging is a snap if you own a single-family home with a garage, can afford to have a fast charger installed, and rarely drive farther than an EV can go on a single charge. But it you live in an apartment or have to park on the street, you are suddenly exposed to the maddening world of public charging. A Wall Street Journal reporter recently did a tour of public chargers in the Los Angeles area, which has a relatively robust charging infrastructure, only to find that 40 percent of them had serious [problems].”

—Megan McArdle, “The Best Way to Get Everyone into Electric Cars? Hint: It’s Not a Mandate,” The Washington Post, March 25, 2024